Harm Reduction Strategies—A Primer

The Carlat Addiction Treatment Report, Volume 8, Number 1, February 2020

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/catrv8n1/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Free Articles | Hepatitis | HIV | Opioid epidemic | Overdose | Prevention

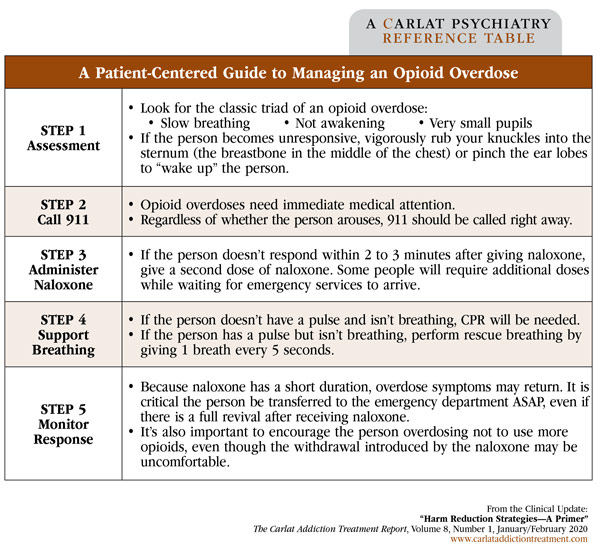

As is frequently the case with chronic diseases, cure is often neither possible nor an appropriate goal in addiction treatment. That’s where the concept of “harm reduction” comes in. Such strategies can help prevent death, serious injury, or other negative consequences of substance use in patients who are continuing to use drugs or struggle with addiction. In this article, we’ll cover four practical harm reduction strategies that can be employed in many office settings: overdose education and naloxone distribution, syringe and needle exchange, fentanyl testing, and pre-exposure prophylaxis. Overdose education and naloxone distribution Naloxone strongly binds to and blocks opioid receptors, kicking off other opioids and reversing their effects. It should be used if someone is experiencing respiratory depression—struggling to breathe or not breathing at all. Naloxone for overdose reversal comes in intramuscular (IM), intravenous (IV), subcutaneous (SC), and intranasal (IN) formulations—though only certain IM/SC and IN versions are given for laypeople to use. By pairing overdose education with naloxone distribution, someone witnessing an overdose can not only recognize what is happening but also act to reverse it. IM naloxone comes in a kit with a vial and needle used to draw up the 0.4 mg/1 mL solution. There is also an IM/SC auto-injector with audible prompts and a retractable needle. IN delivery is easier for laypersons since no needles are involved. There are two types of IN naloxone kits—one single-step kit with 4 mg/0.1 mL (Narcan) to be sprayed in one nostril and another multi-step kit with 2 mg/2 mL, spraying 1 mL in each nostril with the use of an atomizer device that the user must attach to the syringe. Each of the formulations comes with two doses of naloxone—the second dose is to be administered after 2 to 3 minutes if there is no response. When prescribing naloxone, it is sometimes helpful to discuss with your local pharmacy the formulations they carry and which ones are on the patient’s insurance formulary. The CDC’s Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, published in 2016, recommended OEND to any patient or household member of a patient receiving opioids who has a history of overdose, is prescribed high doses of opioids (> 50 morphine mg equivalents per day), has a history of a substance use disorder, or is also taking benzodiazepines (Dowell D et al, MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65(1):1–49). Any prescriber can prescribe naloxone, and states now have “standing orders” or “pharmacy access laws” allowing anyone to access naloxone without a prescription (and often covered by that person’s prescription insurance plan). (For links to specific state laws, see: www.tinyurl.com/w8o936s.) It should be noted that some individuals, including health care providers, have been denied life insurance because of filling a naloxone prescription. This is an unfortunate barrier to expanding access to naloxone. Patients and health care providers filling prescriptions for naloxone may wish to contact life insurance providers to explain their reasoning for doing so. Syringe and needle exchange Syringe exchange programs can also be entry points for patients into various forms of treatment, including viral infection testing, referrals to both infectious disease and addiction treatment, overdose education, naloxone distribution, and safer sex and injection counseling (Des Jarlais DC, Harm Reduct J 2017;14(1):51). The North American Syringe Exchange Network has a map to locate syringe exchanges in your state and other substance use resources: www.nasen.org/map. These programs are recorded by self-report only and are currently listed in 39 states. Some pharmacies may also dispense syringes. While some states require a prescription, many allow over-the-counter sales. For a good resource that lists specific policies in your state, see: www.tinyurl.com/tbtal7b. Fentanyl testing People who use opioids may be unaware that fentanyl has contaminated their drug supply. To empower people who use opioids with this information, fentanyl testing strategies are becoming more common. Fentanyl test strips can be applied to a small sample of heroin after mixing it with water—or to the rinse-water after a batch of heroin is cooked up—and within 1 minute a person can know if fentanyl is in the sample or not. When used in this way, the test strips have been found to be > 96% sensitive and > 90% specific for fentanyl (www.tinyurl.com/t8osks5). While test strip distribution to people who use opioids is still new, evidence supports inclusion of fentanyl testing in comprehensive harm reduction programs (Goldman JE et al, Harm Reduct J 2019;16(1):3). Inquire with your local harm reduction organization or syringe exchange program about the availability of fentanyl test strips. Pre-exposure prophylaxis CATR Verdict: Harm reduction strategies have been proven to reduce negative consequences of opioid use, can empower patients to make more informed choices about drug use, and can serve as entry points into other treatment services. The strategies outlined here—OEND, syringe exchange, fentanyl testing, and PrEP—not only reduce harm but save lives. Get to know local harm reduction policies and programs where you can refer your patients, or get involved yourself to offer some or all of these services. Table: A Patient-Centered Guide to Managing an Opioid Overdose

Overdose education and naloxone distribution (OEND) is a strategy emphasized by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration in their practical recommendations to curb the epidemic of opioid-related deaths (SAMHSA Overdose Prevention Toolkit 2018, www.tinyurl.com/qq3hem2). Overdose education means teaching laypeople to recognize signs of an opioid overdose as well as factors involved in higher-risk drug use—mixing opioids with other sedatives, using alone, and using increasingly higher doses. Opioid overdose education may target people who use opioids; however, it’s less likely that opioid users will curtail their drug use proactively and far more likely that peers and bystanders will intervene on the behalf of someone who is overdosing. With this in mind, overdose education is expanded to anyone likely to witness an overdose (Kerensky T and Walley AY, Addict Sci Clin Pract 2017;12(1):4). This includes family members or friends of people who use opioids, medical personnel, and emergency response technicians.

Another harm reduction strategy specifically for IV drug use is syringe and needle exchange. Exchange programs are designed to reduce the spread of infections from sharing needles, including hepatitis B and C, HIV, or soft-tissue infections such as abscesses. They safely dispose of used syringes and needles and provide sterile injection equipment to patients. These programs were first developed in the 1980s as the AIDS epidemic erupted; they have since become more widespread. As you might expect, syringe exchanges are more controversial than OEND programs because they directly provide drug paraphernalia. However, over the past three decades, syringe exchange programs have been associated with decreasing prevalence of viral infections. For example, New York’s legalization of syringe exchange programs between 1990 and 2002 was associated with a decrease in HIV incidence in the drug-injecting population, with a strong inverse relationship between HIV incidence and the number of syringes distributed (Des Jarlais DC et al, Am J Public Health 2005;95(8):1439–1444).

Fentanyl has been a major contributor to overdose deaths since 2013 and is now widely found in the North American heroin supply. In 2017, more than 28,000 deaths involving synthetic opioids like fentanyl occurred in the United States, more deaths than from any other type of opioid (Scholl L et al, Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;67(5152):1419–1427). West Virginia, Ohio, and New Hampshire had the highest death rates from synthetic opioids. Fentanyl’s deadliness lies in its higher potency and strong receptor affinity, which means that large doses of naloxone are required to reverse respiratory depression from a fentanyl overdose. Even a few grains of fentanyl contaminating a supply of heroin or other opioid can be lethal.

Another harm reduction strategy for preventing the spread of HIV is offering pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for people who inject drugs. (PrEP is also indicated for patients otherwise at increased risk for HIV infection.) PrEP is the daily use of antiviral medication in order to prevent the spread of HIV (see CATR Nov/Dec 2019 for more detail); the medication used is typically either Truvada (emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate) or Descovy (emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide). Discuss PrEP with anyone who is sharing injection equipment or who is at increased sexual risk for HIV infection (US Preventive Services Task Force; Owens DK et al, JAMA 2019;321(22):2203–2213). In most clinical trials of PrEP in these populations, HIV infection rates were reduced by 50%–85%, depending on the adherence rate.