ADHD Overdiagnosis

The Carlat Psychiatry Report, Volume 15, Number 1, January 2017

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/tcprv15n1/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: ADHD | Practice Tools and Tips

Alyson Harrison, PhD

Alyson Harrison, PhD

Clinical director, Regional Assessment and Resource Center, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario

Dr. Harrison has disclosed that she has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

TCPR: You run a screening clinic for adult ADHD at Queens University near Ottawa. You’ve had some interesting findings; can you describe them?

Dr. Harrison: Sure. The people that I see are generally university students who think they have ADHD but who were never diagnosed. Most of them were referred by a family physician, a counselor, or an academic advisor. We do an extensive evaluation to see if they meet DSM criteria. We now have data on 260 students, and we found that only 5% met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for ADHD—that’s only 14 people in total. The title of the forthcoming paper (currently being prepared for review) reporting these results is “Think Horses, Not Zebras,” because if you’ve got a never-before-diagnosed young adult or adult coming into your office saying, “I think I have ADHD,” chances are 95 out of 100 that the cause is something else.

TCPR: That’s pretty remarkable. So what do you make of the 95% who thought they had ADHD?

Dr. Harrison: If you look at the symptoms of ADHD—inattention, problems concentrating—those same symptoms get listed in just about every condition in DSM. A few years ago, one of my grad students did a study where she looked at all the students in a first-year university psychology course; she had them complete a self-report checklist of ADHD symptoms, and at the same time complete a checklist evaluating levels of depression, anxiety, and stress. She found that the more depressed, anxious, and stressed students were the most likely to report higher levels of ADHD symptoms (Alexander SJ and Harrison AG, J Atten Disord 2013;17(1):29–37). And these were all young adults who had never been diagnosed with ADHD before. For the second part of her study, she had students who were coming into student health services complete the checklists and found that 33% of these students (who had never before been diagnosed with ADHD) scored high on self-report symptoms of ADHD (Harrison AG et al, Canadian Journal of School Psychology 2013;28(3):243–260). The implication is that the more stressed, depressed, anxious, and sleep-deprived someone is, the more likely they are to report symptoms of inattention and problems concentrating.

TCPR: So it isn’t that people are necessarily feigning ADHD?

Dr. Harrison: Correct; it’s that sometimes they’re looking for an answer when they are feeling stressed or depressed. Patients report to us that they often go online looking for answers, and when you look online for information about stress and problems concentrating, you’re going to find a lot of information about ADHD. But the sites often don’t emphasize that you have to have a history of symptoms, and that you have to meet criteria for symptoms other than inattention.

TCPR: So some people are looking for solutions to their distress and latch onto ADHD as a possibility; they are not feigning the symptoms. But I assume there are plenty of people out there who are faking a diagnosis—do you see that as a problem?

Dr. Harrison: It is. There’s a webpage called “How to Convince Your Shrink You’ve Got ADHD” (http://tinyurl.com/crc4ldn). It lists all the questions a psychiatrist is likely to ask, and tells you how to answer each one to increase the chances of getting a diagnosis and prescription for a stimulant. But even in these cases, it’s not always simply people trying to abuse the drug, though of course that happens—they will also use it as a study aid. I’ve had a number of students who have admitted that they were just trying to exaggerate symptoms in order to be competitive. They will say, “Well, I have to be able to keep up with all the other people who want to get into med school or law school.”

TCPR: What are some of the things we can be asking to help distinguish true ADHD from the various versions of feigned ADHD?

Dr. Harrison: Clinicians sometimes forget that there are five things you need to establish in order to make the diagnosis, and only one of them is having a sufficient number of symptoms. According to DSM-5, you also have to show that the symptoms were present before age 12, that they’ve been present in 2 or more settings, that they substantially impair the person in those settings, and finally, that they can’t be better explained by something like anxiety or depression.

TCPR: And what are some of the questions you ask in your screening clinic in order to assess whether someone’s condition is really ADHD?

Dr. Harrison: One of the first questions we ask is, “When did your symptoms first start?” If they say, “First year of university or the last year of high school,” then it can’t be ADHD according to the criteria. We’ll also ask, “How did the symptoms substantially impair you? Have you had car accidents? Do you run red lights? Have you had sexually transmitted diseases because you hadn’t thought ahead to take precautions? Have you been arrested? Have you lost jobs? Have you been formally reprimanded?”

TCPR: And what type of answers do you get from people who are more likely to have ADHD?

Dr. Harrison: The patients that I see who really have ADHD will say, “I can’t drive because I just can’t keep my mind focused on what I’m doing. I’ve been fired from all these jobs because I sleep in late or I forget. I’ve lost relationships because I’m just not paying attention. I lost my electricity because I forgot to pay the bill.” And then there are other patients who say, “I haven’t had any of those kinds of consequences, but I know I could have done better.” Well, there are a lot of people who “could have done better.” They could have been a contender in the Olympics, but instead they’re just the national champ or the state champ. That doesn’t mean that they’re disabled.

TCPR: So it sounds like you do a bit of digging to really ascertain what’s going on.

Dr. Harrison: Right. And in the young adult age group, substance use is common, so I do a thorough history. I don’t just say, “Do you drink alcohol or use drugs?” I’ll say, “What drugs have you have tried?” and, “When you drink, what do you like to drink?” We’ve had patients who say, “I’m smoking marijuana. I’m going through 2 or 3 grams a day.” One guy said he drank sometimes, and I said, “So if you went out with your friends for an evening, how many beers would you go through? 24 or so?” His response was, “Yeah, that sounds about right.” It’s important to keep in mind that in the late teen years, lots of kids are stressed out; they’re anxious; they’re not sleeping well. And many of the people that we see tend to be pretty high achievers and are worried about getting good grades. And their problems begin around late high school when they realize they need to have good enough grades to get into a competitive post-secondary program. So, again, it’s important to investigate that a little more first before we jump on the ADHD bandwagon.

TCPR: Is it possible you’re interpreting the criteria too stringently by requiring such serious symptoms of disability as getting fired and getting into accidents? If we required such symptoms, wouldn’t we end up turning away people with milder versions of ADHD who might benefit from medication?

Dr. Harrison: That’s possible, but we have a responsibility to minimize harm, and if there are other more salient and likely explanations for the problems, then I think it’s irresponsible to write a prescription. After all, we know lots of people would benefit from stimulants regardless of whether they have ADHD.

TCPR: Can you give us an example?

Dr. Harrison: Sure. We had a PhD student present to our clinic who had won all sorts of awards as an undergrad and won a full scholarship for graduate study. He came to our clinic saying he thought he had ADHD. He knew that we were only a screening clinic, and that we wouldn’t be prescribing the medication even if we diagnosed him with that problem, so we asked him, “Why don’t you just go to your family physician?” He rolled his eyes and said, “Okay, I’ll level with you. I can’t go to my family doctor.” And we said, “Why not?” He responded, “Because he’s known me all my life.” We said, “Well, that’s perfect.” He argued, “No, it’s not. He knows I don’t have ADHD.” Then he said, “Look, I’m tired of paying $20 a pill to get Adderall in my dorm, but if you guys diagnose me, then the university health plan will pay for it. Everyone else is staying up late and writing papers, and I need to be awake and alert to stay competitive.” He knew all the right things to say about the symptoms, but it was pretty hard for him to say objectively anything to help us see where those symptoms had impaired his life.

TCPR: And of course, the problem is that we have no biomarker for ADHD.

Dr. Harrison: Correct. DSM tries to draw this arbitrary line in the sand to say, “Once you’ve passed this line, you probably have it.”

TCPR: In clinical practice, the situation is not as clear-cut as with grad students. We might see 30- or 40-year-old adults who tell us that they are having concentration problems—their spouse is complaining about them not listening to a conversation, or their attention is wandering at work. They ask for a stimulant, and while you may not be certain they have ADHD, you give them a trial prescription. They come back in a month and they say it’s working, and they get another refill, and then another; then suddenly it’s five years later and they feel they have a God-given right to their stimulant. So there are two parts to the problem: First, we are not doing a good enough job establishing the diagnosis in the first place, and second, we are not adequately assessing whether the meds are actually doing anything.

Dr. Harrison: In terms of getting the diagnosis right, it’s important to remember that genuine ADHD is a disabling condition, and logically, you’d think if somebody has gone through their whole life up to age 30 or 40 really suffering from ADHD, there should be some sort of paper trail. There should be some sort of history to show how this condition has disabled them as opposed to a verbal report that they’ve just always had some problems with paying attention or focusing. As an analogy, if you’ve been quadriplegic all your life, there should be some evidence to say that you can’t get around or move very well without someone else helping you. So in our interviews we will go into some depth, and we actually get them to bring in their old report cards. It’s pretty hard to say that you’ve been impaired by your symptoms if you’ve always gotten A’s in school and you were on the dean’s list and you were the valedictorian. Maybe they had some symptoms, but without impairment, it’s not a disorder.

TCPR: That makes sense. And after a prescription, we should spend more time nailing down some target symptoms or behaviors that we can ask about every appointment, so we can figure out whether the medication is actually doing something for the patient.

Dr. Harrison: I had a student whose parents were very reluctant to have him on medication, but his family physician had put him on it. Even the student wasn’t 100% convinced he had ADHD. And I said, “Let’s just do an experiment. Let’s look at some target behaviors and create a questionnaire tailored to you. Give the questionnaire to people who know you and see how they rate your symptoms. Then go off your medication for a couple of weeks, without telling them—then have them rate you again.” What was interesting was that there was a halo effect: People assumed this guy was on medication, and they kept saying that he was great 100% of the time even when he was off his meds. Both he and his parents concluded that it really wasn’t clear that he had ADHD, or that he was responding to medication.

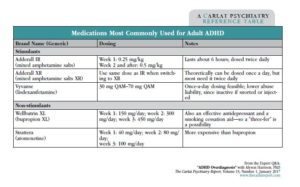

Table: Medications Most Commonly Used for Adult ADHD

TCPR: That’s very interesting. Thank you for your time, Dr. Harrison.