Non-Addictive, Pharmacological Options for Sleep

The Carlat Addiction Treatment Report, Volume 6, Number 6, September 2018

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/catrv6n6/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Addiction | Free Articles | Psychopharmacology Tips | Sleep Disorders | Substance Abuse

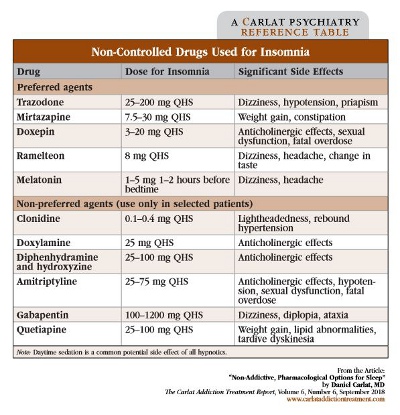

Daniel Carlat, MD Publisher, The Carlat Addiction Treatment Report Dr. Carlat has disclosed that he has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity. In this month’s interview with Dr. Eric Hermes, we learned about his approach to treating insomnia in patients with substance use disorders, with a focus on cognitive behavioral therapy. In this article, we’ll look at some non-addictive pharmacological options. That means we’re not going to review any of the benzodiazepines or the non-benzodiazepines (eg, “Z drugs”), such as Ambien, Sonata, or Lunesta. While the non-benzos are probably less addictive than benzos, they often seem to make their way into recreational drug cocktails when in the hands of patients with SUDs, so they’re best avoided in this population if possible. Sedating antidepressants Mirtazapine. Mirtazapine (Remeron) is a very effective triple-use medication that can target depression, anxiety, and insomnia. Though only FDA-approved for depression, it works for anxiety at doses used for insomnia. There is some credible evidence that it is more effective for sleep at low doses (15 mg) than high doses (30 mg and higher) (Savarese M et al, Arch Ital Biol 2015;153(2–3):231–238). The putative reason for this is that at low doses mirtazapine is primarily an antihistamine, whereas at higher doses it increases norepinephrine release, which can be stimulating. However, some psychiatrists say they haven’t seen this dosing effect in their practices, so it might just be psychopharmacology lore. The unfortunate drawback is that mirtazapine causes weight gain in many patients, a side effect that you can’t prevent by using low doses. Orthostatic hypotension is an under-appreciated side effect, especially in the elderly. Doxepin. Doxepin (Silenor) is a tricyclic that has been around for a long time as an FDA-approved treatment for depression and anxiety. At low doses (10 mg–20 mg of generic doxepin, or 3 mg–6 mg of Silenor), it is an effective hypnotic with relatively few anticholinergic side effects. Amitriptyline. Amitriptyline (Elavil) is another sedating tricyclic, with insomnia doses typically in the 25 mg–75 mg range. It has the bonus of being effective for a range of pain issues, including fibromyalgia, migraine headaches, diabetic neuropathy, and post-herpetic neuralgia. So you can potentially avoid two classes of addictive medicines with this drug: benzos and opiates. The antihistamines Doxylamine (NyQuil and others). Think of doxylamine as very similar to diphenhydramine; it works just as well and is usually dosed at 25 mg. Use doxylamine for patients who tell you diphenhydramine doesn’t work for them—they may well respond to this alternative. Hydroxyzine (Atarax, Vistaril). Hydroxyzine has been around since 1956 and has FDA indications for pruritis, anxiety, and sedation before surgery. Confusingly, there are two versions of hydroxyzine: hydroxyzine HCL (Atarax) and hydroxyzine pamoate (Vistaril). During medical training, some of us might recall being taught that Atarax is the version to use for itching while Vistaril is better for anxiety. But there’s no truth to this rumor, which is an artifact of Vistaril’s unique availability as a fast-acting injection for anxiety. At any rate, hydroxyzine is a favorite among inpatient psychiatrists for use as a “prn” for anxiety, but it works well for insomnia too. Prescribe 25 mg–100 mg at bedtime and warn patients about next-day sedation. The melatonin receptor agonists Ramelteon (Rozerem). Ramelteon is a prescription product approved for insomnia and is a melatonin receptor agonist. Although it clearly outperforms placebo in clinical trials (see the 2014 meta-analysis: Kuriyama A et al, Sleep Med 2014;15(4):385–392), patients often don’t feel like it’s working because they don’t detect a sedating sensation. Often patients say it doesn’t start working for several days, so you have to encourage them to stick with it for a while. There’s no notable next-day sedation. Prescribe it 8 mg at bedtime. Since it’s not available generically, it may be hard for some patients to obtain. Other sedating drugs Quetiapine (Seroquel). Prescribed at 25 mg–100 mg at bedtime, quetiapine, for better or worse, has become a go-to sedative for those who shouldn’t take benzos. We worry about the potential for weight gain and hyperlipidemia. It’s not clear that weight gain on quetiapine is dose-dependent, but it’s likely that very low doses don’t cause much weight gain. For example, in one study of 534 adults on quetiapine doses of 100 mg or less, the average weight gain was 2.2 pounds after 12 months. While this was not a controlled trial, this amount of weight gain is lower than what’s usually reported for quetiapine at antipsychotic doses. But even at low doses, you should monitor weight and lipids periodically. Clonidine. Clonidine (Catapres) is an alpha-2 agonist that was initially used for hypertension. Over time, it has become clear that it’s also helpful for hyperarousal states, such as ADHD, opioid withdrawal, anxiety, and insomnia. Clonidine is a favorite of child psychiatrists treating insomnia in children, but it likely works as well for adults. Start most patients on 0.1 mg at bedtime, and increase as needed up to about 0.4 mg. Since it relaxes blood vessels, it can cause lightheadedness, which you should warn patients about (though this is rarely a problem for patients taking it at bedtime). Another issue to watch out for is rebound hypertension after suddenly stopping the medication. Be sure to taper the dose gradually when discontinuing clonidine in patients who use it chronically. CATR Verdict: There are plenty of non-addictive hypnotics for your patients with SUDs. Just go down the list and you’ll find something that works. If you don’t, it’s probably because your patient is trying to wear you down until you unleash the “good stuff”!

Trazodone. Trazodone, which is an antidepressant that has never been FDA-approved for insomnia, turns out to be the second most prescribed sleeping pill in the U.S. (Bertisch SM et al, Sleep 2014;37(2):343–349). It is typically started at 25 mg–50 mg, but some patients will respond to 12.5 mg, while others require doses greater than 150 mg. Usually once patients are using those higher doses, they will start requesting to switch to something else. You’ve probably been prescribing trazodone for many years, but chances are slim that you’ve actually seen data for its effectiveness in insomnia. A recent meta-analysis should ease your mind. An analysis of 7 trials evaluating trazodone found that it is more effective than placebo, and that both high and low doses are helpful, with the main effect seen for sleep maintenance as opposed to sleep initiation (Yi XY et al, Sleep Med 2018;45:25–32).

Diphenhydramine (Benadryl and others). The effective and starting dose is 25 mg–50 mg, though it can be effective at doses as low as 6.25 mg. Next-day grogginess seems to be a common problem with diphenhydramine, as well as pretty rapid development of tolerance—sometimes within a few days. In terms of anticholinergic side effects, the one we’re most concerned about is cognitive impairment, which is primarily a problem in older patients with long-term use.

Melatonin. The melatonin you can buy at the drugstore is the synthetic form of the natural hormone, which is secreted by the pineal gland. Its blood levels typically rise at sunset and peak in the middle of the night. A recent meta-analysis of 12 studies comparing melatonin to placebo concluded that melatonin improves insomnia in patients with sleep onset difficulties (Auld F et al, Sleep Medicine Reviews 2017;34:10–22). Additionally, a few small studies have found that a newer extended-release melatonin product may aid in maintaining sleep. The dose is highly variable, and the meta-analysis reported that the doses used in clinical trials ranged from 0.3 mg to 10 mg, with most between 2 mg and 5 mg. Don’t forget to tell your patients to take their melatonin several hours before sleeping; it’s unlikely to work if taken right at bedtime.

Gabapentin (Neurontin). Even though gabapentin has gotten bad press recently related to the possibility of recreational use, it’s not as addictive as the benzos, and the majority of those who get into trouble with it are also misusing opioids. Gabapentin is a highly popular medication, in part because it causes few drug interactions; therefore, prescribers feel comfortable using it in patients on multiple medications. There’s no question that some patients find gabapentin sedating. For insomnia, start at 100 mg QHS and titrate upward as needed.