Reducing the Stigma of Addiction Through Language and Terminology

The Carlat Addiction Treatment Report, Volume 8, Number 2, March 2020

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/catrv8n2/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Disparities | Engagement | Free Articles | Opioid Use Disorder | Stigma

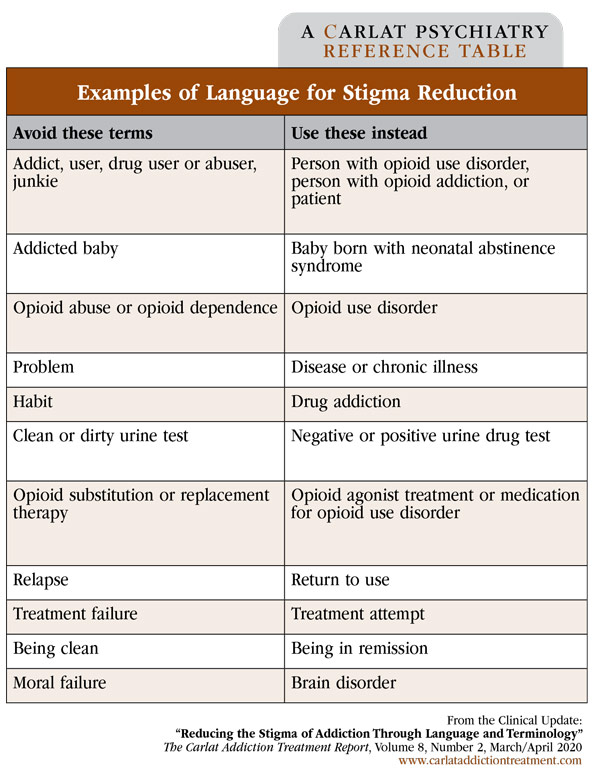

The words we use in discussing addiction shape the way our patients, fellow clinicians, and communities think about substance use disorders. Addiction has long been viewed as a moral failing, and the terminology of addiction has reinforced this belief. Here, we review the evidence that documents how terminology can perpetuate—or reduce—the stigma associated with substance use disorders and highlight specific recommendations that may promote better engagement in care. In the US, for each person meeting the criteria for a substance use disorder, only 1 in 10 is in treatment each year (Kelly JF et al, Am J Med 2015;128(1):8–9), and stigma heavily drives this gap in care. In the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 16% of people who needed or perceived a need for addiction treatment did not seek it because of concerns that doing so would have a negative effect on their job, and 15% did not seek treatment because they felt that neighbors or community members would develop a negative opinion of them (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019; www.tinyurl.com/t5qkbc7). The language we use can fuel this stigma. Using words like “junkie,” “dirty,” “abuse,” or even “drug habit” implies a higher degree of choice than what we know to be true about addiction. The public, as well as clinicians, respond very differently when they believe an illness is driven by bad behavior or a moral failing vs a genetic predisposition (Richter L and Foster SE, J Public Health Policy 2014;35(1):60–64). We as clinicians are not immune to the effects of language on our decision making. In a randomized controlled trial, mental health professionals attending two conferences were asked to read a vignette about an individual, both versions of which were identical except that one used the term “substance abuser” (more stigmatizing) and the other used the term “having a substance use disorder” (less stigmatizing). The professionals were then asked to complete various Likert rating scales about the vignette. Those who read the “substance abuser” vignette were more likely to rate the individual worse on the perpetrator-punishment scale, meaning that they believed the patient was more personally responsible for the actions taken in the vignette. In fact, these clinicians were more likely to recommend punitive action (Kelly JF and Westerhoff CM, Int J Drug Policy 2010;21(3):202–207). It’s easy to see how that perception could lead to different actions taken in treatment planning or drug court settings. Various organizations have taken up the call to change the language surrounding addiction. The DSM-5 has changed the diagnoses we use from “abuse” or “dependence” to “substance use disorder,” as the term “abuse” is associated with negative judgments and punishment. The International Society of Addiction Journal Editors put forth a statement in 2016 calling for a shift in terminology, emphasizing an end to stigmatizing language and promoting more clinical, recovery-oriented terms (Saitz R, J Addict Med 2016;10:1–2). The White House Office of National Drug Control Policy issued a statement in 2017 calling for all federal agencies to change from the old language of personal failure to new language recognizing addiction as a brain disorder (www.whitehouse.gov; full website is www.tinyurl.com/y78bnpyg). Even the general public is seeing a shift in language. The 2017 edition of the Associated Press Stylebook advocated for less pejorative and more person-first language when writing about addiction. Recommendations included avoiding words like “abuse” or “problem” and instead using “use” with an appropriate modifier such as “risky,” “unhealthy,” “excessive,” or “heavy.” Another recommendation was to avoid terms like “alcoholic,” “addict,” “user,” and “abuser” in favor of “a person with a substance use disorder” (Associated Press. The Associated Press Stylebook 2017 and Briefing on Media Law. New York, NY: Basic Books; 2017). Table: Examples of Language for Stigma Reduction The table above highlights some specific terminology recommendations consistent with DSM-5, the AP Stylebook, and the recommendations of addiction journal editors. As we work to expand access to addiction treatment—such as by increasing the pool of addiction providers and promoting novel care delivery programs, including telehealth—the terminology we use with patients, colleagues, and society at large can help reduce the shame and fear that keep patients from seeking treatment. CATR Verdict: Language can influence perceptions of addiction and drive patients away from care. National organizations have issued guidelines advocating for more person-centered terminology. We should try to use precise clinical language in our role as addiction treatment providers. Doing so can reduce stigma and may lead to better patient outcomes.