Managing Video Gaming in Children and Teens

The Carlat Child Psychiatry Report, Volume 11, Number 7&8, October 2020

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/ccprv11n7-8/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Computer addiction | electronic use | Free Articles | videogaming addiction

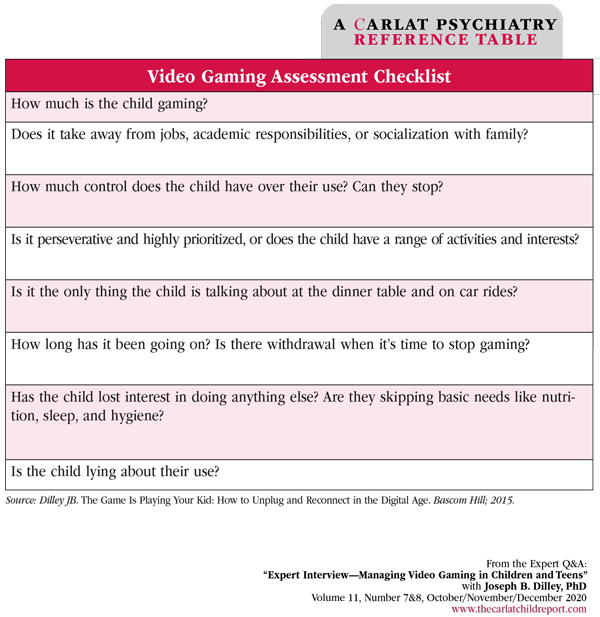

Psychologist in Pasadena, CA; author of The Game Is Playing Your Kid: How to Unplug and Reconnect in the Digital Age (Minneapolis: Bascom Hill; 2015). Dr. Dilley has disclosed that he has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity. CCPR: We are here to talk about managing video gaming in children and adolescents, which is a ubiquitous habit that might be even more pronounced given that we’re in the middle of a pandemic. Dr. Dilley, can you start with the relationship between mood disorders and gaming? CCPR: And unchecked video gaming in the presence of depression can impede all other treatment efforts and prolong the dysfunction. CCPR: Tell us about the impact of violent content in video games. CCPR: Really interesting. What about people staying up late and sleep problems? CCPR: The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends 2 hours a day of screen time. But that’s obviously been especially difficult recently, since kids have been stuck at home and school’s been online with the pandemic. CCPR: How can we assess the extent of the problem more fully? CCPR: Do you have any magic words to open the conversation with kids, so that they’ll be more willing to participate in a discussion that they think is fair? CCPR: Are there other symptoms that we should be looking for in terms of a dysfunction surrounding gaming? Table: Video Gaming Assessment Checklist CCPR: How do we support families with practical strategies? CCPR: In your book, you talk about key behavioral pathways that we can use with families. Can you share an example? CCPR: Kids can be sensitive about this topic. How do you break the ice to talk with the child about changing their gaming habits? CCPR: Even with this strategizing, it can be hard for kids when you actually try to make these changes. Can you talk about the internal reward that kids get when they are gaming? CCPR: What other research do we need to be doing on this? CCPR: Speaking of benefits, there’s been a lot of hype recently about a prescription game that’s FDA approved to treat ADHD. Do you have any thoughts on that? CCPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Dilley.

Joseph B. Dilley, PhD

Joseph B. Dilley, PhD

Dr. Dilley: There is a complex relationship between mood disorders and gaming, with mediating factors. Sometimes kids retreat into games because they’re already depressed. They’re not necessarily becoming depressed because of gaming. But if kids spend too much time gaming, play really violent content, or do it to escape the responsibilities of the real world, the probability of depression is higher. King et al list everything from genetics, personality, upbringing, and specific electronic exposures as part of the WHO-recognized hazardous gaming disorder (King DL, JAMA Psychiatry 2020;77(8):869–870).

Dr. Dilley: That unchecked part is dangerous, like unchecked financial spending or unchecked drinking.

Dr. Dilley: In the famous Bobo doll experiment of the 1960s by Albert Bandura, preschoolers became aggressive after watching a video of a Bobo doll getting knocked down. Although those early studies show that we emulate what we see, video gaming studies do not show a meaningful association between gaming and aggressive behavior. We need to be careful not to automatically blame gaming when kids act out. In fact, the quality of social interactions during gaming can be protective. When kids are gaming heavily in an environment that they experience as socially supportive, in games where they collaborate as a team, that can mitigate symptoms of depression. This mitigation is in contrast with cyberbullying on social media.

Dr. Dilley: Blue light inhibits the release of melatonin, a natural sleep agent. That comes from Matthew Walker’s seminal book Why We Sleep (New York: Scribner; 2017). Other studies show total sleep time decreases as a function of exposure to screen time, particularly gaming. In part, that’s because of increased sleep onset latency. The time it takes to fall asleep after gaming increases, and we end up with less total sleep time. Plus, screen time alters REM sleep and slow-wave sleep. Participants in research studies self-report higher rates of fatigue, and they perform less well on verbal memory and sustained attention tasks as a function of both poor sleep quality and lower sleep time (Peracchia S and Curcio G, Sleep Sci 2018;11(4):302–314).

Dr. Dilley: Right. And if a child is spending 3 or more hours a day gaming, the cognitive benefits that can come from gaming—like cognitive flexibility, attention, visual-spatial perception, and reasoning—disappear or at least diminish. Look at how the child behaves, thinks, and performs after various kinds and lengths of screen time. Also look at motive. Are they retreating into the screen to get away from reality? Or are they taking a break like we all need?

Dr. Dilley: Involve collateral informants and do conjoint and family consultations and sessions. Kids (and adults) tend to under-report their own screen use. Apps that track weekly screen time can also be useful. I like to ask parents that “miracle” question: “If you woke up tomorrow and you were confident there was no problem, particularly with screen use, how would you know?” The parent might reply: “His behavior would be different, his grades would be higher, his level of engagement and willingness to come to the dinner table would increase.”

Dr. Dilley: It might go something like: “Help me understand from your perspective. What’s it like when Mom comes into your room to check on what you’re doing?” The kid might say, “Oh, it’s like she doesn’t trust me, and then she goes and tells Dad, and he gets all upset and he starts yelling.” And you can empathize: “Wow, that sounds really unpleasant,” and so on. Now they’re viewing you as an ally, at least in terms of being able to be heard. It doesn’t mean you’re agreeing with them that they should be able to game all night, but now you’re a validator of their emotional reality. As I am working with kids, I’ll tell them, “Show your parents how much privacy you can handle. Show them what kinds of games leave you in a good mood and what kinds don’t.” I encourage parents to steer clear of “can’t” and “should.” Instead of “You can’t,” it becomes, “You can as soon as you’re ready,” or, “What do you think I need to see to get off your case?”

Dr. Dilley: Video gaming addiction looks an awful lot like other types of addiction. Also look at content/context. Keep in mind that YouTube keeps people watching by algorithmically bringing up the next perfect video to keep them engaged. You want the child to be in control, not the device. You might use a quick checklist to help in your assessment.

Dr. Dilley: It takes a series of conversations in which parents set fair limits and offer credit for shutting down the game early. This strategy paradoxically gets the child more of what they’re looking for by pressing the OFF button, instead of the previous dynamic where ignoring Mom and Dad got the child more screen time. What we ultimately want is kids enjoying themselves and feeling like, “I use screens; they don’t use me.” It sounds idealistic, but it’s attainable, and we need to communicate to parents that managing excessive screen time isn’t so different from managing other temptations.

Dr. Dilley: Sure. A lot of parents will say: “I yelled at him and he still didn’t get off the game.” In this situation, the gaming is more fun than the yelling is noxious, so the intervention doesn’t work. It’s better to reward getting off the game and charge interest for overuse. If the child games past their allowed time, they get less screen time tomorrow. But if the child turns it off early, they get more time to play the next day—say, if they turn the game off one minute early, they get two minutes more time tomorrow. It’s a no-brainer. There’s no yelling, and the child is getting to decide what they do. It’s like the thought process that will happen when the child has a credit card someday: “I can overspend it, but then I’ll owe the amount plus the penalty plus the interest. Hm. I think I’ll just stay within my credit limit.” It’s an experiential learning scenario. And there’s a response cost that’s more effective than traditional punishments like lectures, yelling, hopefully not spanking. Those kinds of punishments, if they’re effective at all, only work for the short term. Also, if the kid can get you to stop yelling or lecturing, then they experience relief, although that is a weaker effect.

Dr. Dilley: I appeal to their desire for independence and privacy, their own self-monitoring capacities, their desire for accomplishment and meaning. I might say: “Wouldn’t it be great if you got to decide how much time you spent gaming and what kind of content you were engaged with?” This is akin to, “Wouldn’t it be great if you had your own car? Your own apartment? Your own scholarship?” and so on. So, they say yes, and we get their buy-in. Then I ask: “What do you think your parents would need to see in order to extend those privileges to you?” The child might respond: “Well, I’d probably need to get my grades up.” Then I can ask whether that seems like an attainable goal: “OK, you think that’s possible?” And they might say, “Well, I work so hard at it, but I keep running into…” Then we get into candid discussions and find some solutions together. When they do better, parents can step back, and we get a new cycle going where Johnny’s performance at home and at school self-perpetuates in a positive direction.

Dr. Dilley: Yes. There’s a dopamine drip that gets activated and becomes more of a surge. So it makes sense that there are tolerance and withdrawal effects, the same kinds of things we see in other dependencies. This can prevent parents from sticking with a new paradigm of enforcement, because they see this extremely high resistance and they go, “Ugh! It was easier when I just gave in and let him keep playing!” I tell parents: “That burst of resistance and defiance is because your intervention is working! They’re having to try harder to get you to cave, and your job is to ride that out so that they develop a new habit.”

Dr. Dilley: We need more longitudinal data on the relationship of mood disorders and gaming over time. We also need to parse out the effects further regarding screen time of all types. I ran into some research indicating that girls, even with a social network, can still have decreased self-esteem from gaming, even in a social context, possibly due to the exchange of more negative affect (Carras MC et al, Comput Human Behav 2017;68:472–479). This is consistent with the significantly higher rate of cyberbullying that goes on among females (Seldin M and Yanez C. Student Reports of Bullying: Results From the 2017 School Crime Supplement to the National Crime Victimization Survey. US Department of Education; 2019). Not all screen time is equal, and not all gaming is bad. Gaming can promote improvement in executive function and in perceptual and spatial function. Some of the research indicates growth in the right hippocampus and plasticity, as evidenced by increased density in gray matter. Are there any other benefits to gaming, and if so, what kind of games confer those benefits?

Dr. Dilley: Brain training games help students get better at brain training games. The question is, what is the generalizability of this impact on executive function? Does it translate into the school scenario, or does it just help someone get better at the game? Are we seeing improvements that translate into real life? What does Johnny’s mom say? What does his teacher say?