How to Use Lamotrigine

The Carlat Psychiatry Report, Volume 19, Number 1, January 2021

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/tcprv19n1/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Bipolar Depression | Bipolar Disorder | Bipolar II | Borderline Personality Disorder | BPD | Hypomania | Lamictal | Lamotrigine | Medication | Mood Stabilizers | OCD | Pharmacology | Psychopharmacology

Chris Aiken, MD.

Chris Aiken, MD.

Editor-in-Chief of TCPR. Practicing psychiatrist, Winston-Salem, NC.

Dr. Aiken has disclosed that he has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Lamotrigine is FDA approved as maintenance treatment for bipolar disorder—that is, for delaying episodes of depression, hypomania, or mania. However, it is not approved for active depression or mania—which has given it a reputation as a “light” mood stabilizer. For patients who appreciate tolerability, that’s a good thing, but it isn’t the first choice when rapid action is needed. In this article I’ll clarify who is most likely to respond to lamotrigine and how to optimize its effects.

When to use it

Lamotrigine’s main use is for prevention, and it’s better at preventing bipolar’s depressive phases than its manic phases. That profile makes it a good choice for patients with bipolar II, who—on average—spend half their lives in depression and 4% in hypomanic or mixed states (Terao T et al, J Clin Psychiatry 2017;78(8):e1000–e1005). In bipolar II, lamotrigine can be used as monotherapy or augmentation, but in bipolar I, it’s best reserved for augmentation because it does not treat mania and is not very good at preventing it.

Lamotrigine’s main drawback is that it is slow to act, which has led to some confusion about whether it works in acute depression.

A checkered history in bipolar depression

Lamotrigine got off to a rough start in the late 1990s when four out of five manufacturer-supported trials failed to show efficacy in acute bipolar depression. Later, two large studies—which were not manufacturer supported—found that it did treat acute depression. So, what happened?

The early, failed studies were monotherapy trials, while the positive studies used lamotrigine as augmentation. But more importantly, the negative studies were shorter, lasting 7 weeks, while the positive trials lasted 8–12 weeks. Lamotrigine has a slow build, taking 4–6 weeks to reach a therapeutic dose. It starts to separate from placebo at 6–7 weeks, and its benefits plateau around 10–21 weeks. At 7 weeks, it’s about half as effective as an atypical antipsychotic, and after a few months its efficacy is similar to an atypical (van der Loos MLM et al, Acta Psychiatr Scand 2010;122(3):246–254; Geddes JR et al, Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3(1):31–39).

In practice, one way around this delay is to start with an antipsychotic for bipolar depression (eg, cariprazine, lurasidone, olanzapine-fluoxetine combo, or quetiapine) and then add lamotrigine as the patient starts to recover. After 6 months of steady recovery, the antipsychotic can be slowly tapered off over 1–2 months (see TCPR Jan 2020, “Antipsychotic Maintenance: How Long Is Enough?”).

Other uses

In bipolar disorder, lamotrigine works well in patients with ultra-rapid mood swings that change on a daily or weekly basis, including cyclothymic disorder. In a placebo-controlled study, lamotrigine reduced those ultra-rapid mood swings by 50% (Goldberg JF et al, Biol Psychiatry 2008;63(1):125–130).

Outside of bipolar disorder, lamotrigine might have a role in borderline personality disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and depersonalization disorder. It’s supported by one or two small controlled trials in each of those disorders (dose range 100–200 mg/day). There was a recent negative trial in borderline personality disorder, but it was hindered by high rates of nonadherence (64%) and dropout (30%) (Crawford MJ et al, Am J Psychiatry 2018;175(8):756–764).

In non-bipolar depression, lamotrigine has had mixed results, but it can be used second-line in treatment-resistant depression (TRD). A meta-analysis of eight randomized controlled trials in TRD found a significant effect in patients with longer and more severe episodes (Goh KK et al, J Psychopharmacol 2019;33(6):700–713).

Rashes

Lamotrigine’s only serious risk is Stevens-Johnson syndrome, which can be fatal if left untreated. Slow titration reduces this risk from 1 in 100 to about 1 in 2,500, but it does not lower the risk of benign rashes, which is quite high at 10% (Bloom R et al, An Bras Dermatol 2017;92(1):139–141). Signs of a serious rash include:

- Painful, scaling, or blistering bumps

- Involvement of the face, palms, feet, or mucous membranes

- Systemic signs like fever, lymphadenopathy, malaise, pharyngitis, or muscle aches

- Eosinophilia or elevated liver enzymes

However, there’s no reliable way to predict which rashes will progress to Stevens-Johnson syndrome. The FDA labeling recommends stopping lamotrigine at the appearance of any rash or fever in the first 2 months, and it’s best to stick with that guidance unless a dermatologist recommends otherwise. Rashes with any of the serious signs above require immediate medical attention and are usually treated with a prednisone taper. To minimize false alarms, advise patients to avoid new soaps and cosmetics, and caution them to avoid sunburn and contact with poisonous plants. Rashes can also appear if lamotrigine is stopped and then restarted after more than 5–7 days, so it’s best to retitrate when treatment is interrupted.

What if the patient improves on lamotrigine but a mild rash forces discontinuation? Retitration is feasible, but you’d need to wait at least a month for the inflammation to settle and reintroduce lamotrigine at an extremely slow rate (start 5 mg/day with the chewable 5 mg tablets and raise the daily dose by 5 mg every 2 weeks until reaching 25 mg/day, then follow standard titration). Several case series have tested that strategy in 97 patients. There were no reports of Stevens-Johnson syndrome, but 15% of the retitrations had to be stopped due to new rashes (Aiken CB and Orr C, Psychiatry 2010;7(5):27–32).

Other side effects

Outside of allergic rashes, lamotrigine is well tolerated and has no serious medical risks. Here are the most common side effects along with measures to mitigate them (Ramey P et al, Epilepsy Res 2014;108(9):1637–1641; Sajatovic M et al, Patient Prefer Adherence 2013;7:411–417):

- Nausea, dizziness, and imbalance: Switch to the XR formulation

- Bitter taste: Switch to the orally disintegrating tablets (ODT)

- Word-finding difficulties: Lower the dose

- Insomnia: Switch to morning dosing

Like antipsychotics and tricyclics, lamotrigine can cause photosensitivity, so sunscreen with an SPF above 30 is a good idea.

Folic acid controversy

A patient once called me after adding folic acid to his lamotrigine, complaining that “I feel as bad as I did before I ever started lamotrigine!” Although folic acid has been found to augment valproic acid and antidepressants, in the case of lamotrigine it may nullify the benefits. That was the surprise finding of a large trial in bipolar depression that randomized patients on lamotrigine to adjunctive folic acid 0.5 mg/day or placebo. The mechanism is obscure but seems limited to a subset of patients with the MET variation at the COMT gene, and does not appear to occur with the CNS-active form of folate, l-methylfolate (Tunbridge EM et al, Bipolar Disord 2017;19(6):477–486). Until we know more about this interaction, I recommend that patients avoid folic acid while on lamotrigine.

Serum levels

Serum lamotrigine levels are generally not useful in psychiatry. However, you might consider it if the patient has an unusual response and you have reason to suspect their level is off (eg, drug interactions or genetic variations at the UGT1A4 or UGT2B7 enzymes where lamotrigine is metabolized). At doses of 100–250 mg/day, serum levels tend to fall in the 2–6 mcg/mL range (Kikkawa A et al, Biol Pharm Bull 2017;40(4):413–418; Douglas-Hall P et al, Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2017;7(1):17–24).

TCPR Verdict: Bipolar disorder requires long-term prevention, and lamotrigine’s tolerability makes it a good choice for this setting. Consider it as monotherapy in bipolar II or as augmentation in bipolar I. Though it can treat acute bipolar depression, it takes about twice as long to work as the atypical antipsychotics.

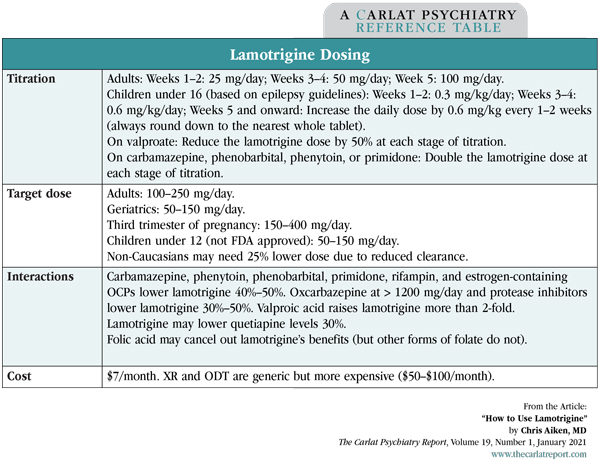

Table: Lamotrigine Dosing