Six Tips for Working With Older Adults

The Carlat Psychiatry Report, Volume 19, Number 4, April 2021

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/tcprv19n4/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information

Topics: Benzodiazepines | Depression | Geriatric Psychiatry | Medical Comorbidities

Rehan Aziz, MD.

Associate Professor of Psychiatry and Neurology, Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School.

Dr. Aziz has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

In the US, 1 in 7 adults are over the age of 65, and the growth in this population is far outpacing the growth in geriatric psychiatrists. As a result, general clinicians are increasingly called on to provide the majority of care for older adults. In this article I’ll share some tips for working with this population.

Tip 1: Communication

Many older adults suffer from some degree of hearing loss. This can cause them to feel left out during appointments and treatment planning discussions. When speaking, I recommend facing the patient and talking clearly and slowly. Speak a little louder than usual, but don’t shout. Repeat yourself as needed. If the patient has one ear that’s better than the other, direct your voice to that side. Use gestures or facial expressions to get your points across. Provide written materials that the patient can refer to later.

Tip 2: Start low and go slow, but then keep on going

Older adults undergo substantial changes in drug metabolism and elimination. You’ll need to adjust your prescribing accordingly.

Metabolism via the cytochrome P450 system is slowed by aging. In particular, this affects the activity of CYP1A2 and CYP3A, resulting in increased blood levels of many drugs. Agents impacted include antipsychotics (aripiprazole, clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone), benzodiazepines (all except lorazepam, oxazepam, and temazepam), carbamazepine, methadone, and trazodone.

In later life, fat stores increase and lean body mass decreases. Most psychotropics are fat-soluble, meaning they’ll be drawn into the excess fat cells. Thus, clinically, their initial effect will be small, but then the drug will release slowly from fatty tissue. This can lead to drug accumulation and toxicity with further dosing. The best way to deal with this is to prescribe smaller doses more often, rather than big doses all at once.

For lithium and other water-soluble drugs such as gabapentin, desvenlafaxine, paliperidone, and pregabalin, the volume of distribution decreases with aging. This means more of the drug is present in the circulation and more of it reaches the brain. Therefore, target levels for lithium in older adults are about 30% lower than they are for younger adults (0.4–0.8 mg/dL, instead of 0.6–1.0 mg/dL).

Kidney function also declines with age, reducing the elimination of many drugs. This results in higher serum concentrations and longer durations of action. The solution is to raise the dose more slowly, aim for a smaller dose, and lengthen the intervals between doses.

Considering all this, we arrive at the old adage to “start low and go slow.” However, unless your older patients are taking lithium or have renal impairment, they will still require some dose titration, so don’t forget to “keep on going.”

Tip 3: Are they depressed?

Most cases of late-life depression go unrecognized. Even when diagnosed, only about 36% of elders with MDD are treated with antidepressants (Steffens DC et al, Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000;57(6):601–607). Antidepressants do work in older adults, and some data suggest they work better than in younger adults. In fact, these medications boast the strongest antisuicide effects in the older population (Erlangsen A et al, Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014;22(1):25–33).

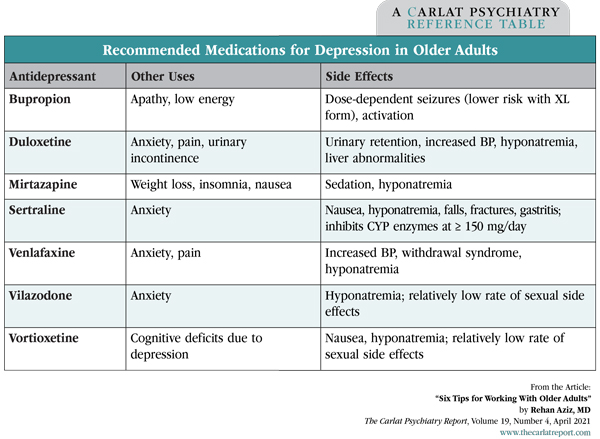

Diagnosing depression in older adults can be challenging as depression can result from many factors, including dementia, medications, or conditions like Parkinson’s disease. The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) is a quickly administered tool that can help. It’s available at www.fpnotebook.com/psych/exam/FvItmGrtrcDprsnScl.htm and comes in several versions—5, 15, or 30 questions, all with simple yes-or-no answers. Even the 5-question version is useful with a sensitivity of 97%, a specificity of 85%, and an administration time of 54 seconds (Hoyl MT et al, J Am Geriatr Soc 1999;47(7):873–878). See the table below for recommendations on antidepressants in older adults.

Table: Recommended Medications for Depression in Older Adults

Tip 4: Avoid memantine in mild cognitive impairment

In recent years, there has been a surge in practitioners ordering memantine for mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia. This may be due to a positive manufacturer-sponsored meta-analysis for memantine in mild Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but the practice is at odds with the FDA labeling, which indicates memantine is only for moderate and severe dementia.

The practice also goes against the data. A recent Cochrane systematic review examined 44 randomized controlled trials involving about 10,000 people, most of whom had AD. Researchers found that while memantine has a small benefit in people with moderate to severe AD, it’s no better than placebo in people with mild AD (McShane R et al, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;3(3):CD003154). Based on this, continue to reserve memantine for later-stage dementias.

Tip 5: Benzos are bad

Older adults have increased sensitivity to benzodiazepines and Z-drugs (eszopiclone, zolpidem, and zaleplon). All benzos and Z-drugs increase the risk of cognitive impairment, delirium, falls, fractures, and motor vehicle crashes. Benzos may be appropriate, though, for refractory panic or refractory generalized anxiety disorder, benzo and alcohol withdrawal, and a few medical conditions (seizures, REM behavior disorder, and periprocedural anesthesia). Otherwise, they should be avoided (American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel, J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67(4):674–694).

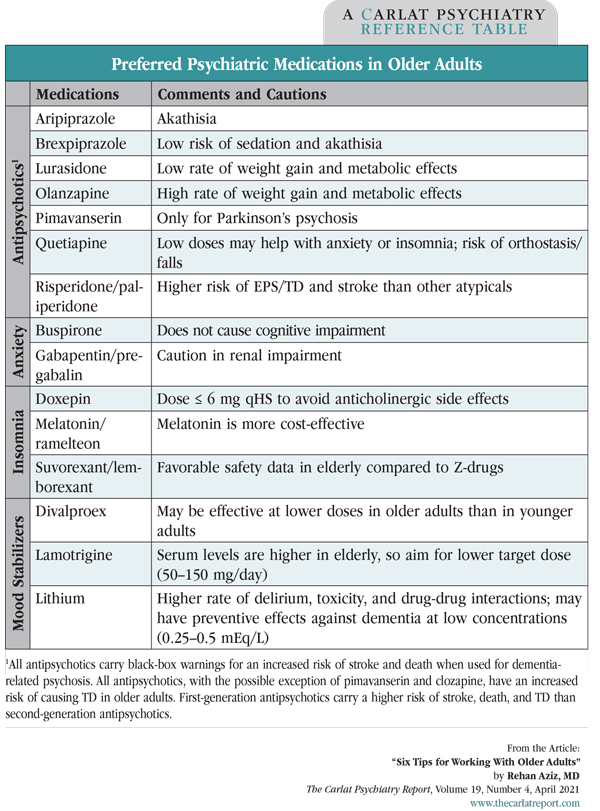

Often, other specialists start benzos in older adults. Our role then is clear—deprescribe them. For safer alternatives, see the “Preferred Psychiatric Medications in Older Adults” table below and the “Recommended Medications for Depression” table above.

Table: Preferred Psychiatric Medications in Older Adults

Tip 6: Meds to use, and meds to avoid

In general, opt for agents that lack significant anticholinergic effects and don’t produce orthostatic hypotension, daytime sedation, or cardiac arrhythmias. For most medications, start at half the usual dose and increase to the minimal effective dose after 1–2 weeks, as tolerated. Increasing the dose sooner or faster is associated with greater side effects but not better response. If possible, tailor medication choices to patients’ comorbid symptoms and side effect profiles (see the table above for ideas). Review their regimens periodically to determine whether you can deprescribe any of the medications.

TCPR Verdict: Older adults require a specialized approach due to increased sensitivity to medications and their side effects.