ECT Worked: Now What?

The Carlat Psychiatry Report, Volume 19, Number 8, August 2021

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/tcprv19n8/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Antidepressant Augmentation | Depression | Depressive Disorder | ECT | Free Articles | Lithium | Treatment-Resistant Depression

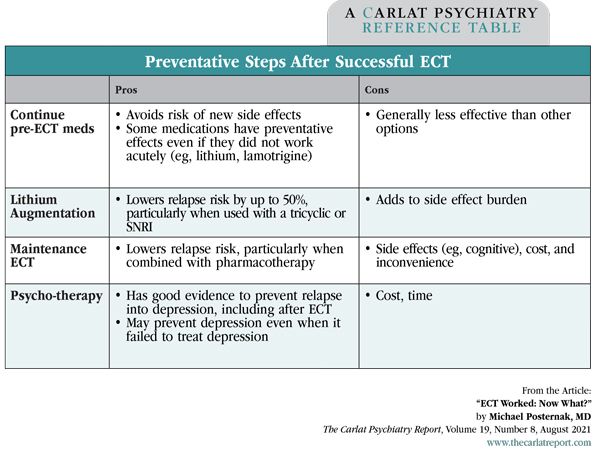

Michael Posternak, MD. Psychiatrist in private practice, Boston, MA. Dr. Posternak has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity. Juan is a 72-year-old man with severe depression who has not responded to numerous antidepressant trials. He is reluctant to undergo a course of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), but agrees to do so if one last medication trial doesn’t work. After failing to respond to escitalopram augmented with aripiprazole, Juan receives a course of ECT and has a terrific response. Feeling better, he asks you what should be done next with his medications. Patients frequently inquire whether any new treatments for depression have come to the market. But newer treatments, unlike new cars, aren’t necessarily better; in fact, older treatments are better studied and are more battle-tested. Nowhere is this more apparent than with ECT, whose treatment effect size (0.9)is one of the largest in psychiatry (Kho KH et al, J ECT 2003;19(3):139–147). But when patients do respond to ECT, we are inevitably confronted with a dilemma: What do we do with their medications that had previously not worked? Three main options exist: 1) Continue the current med regimen in hopes that it will prevent depression (even though it had not previously helped), 2) Switch medications, or 3) Begin maintenance ECT (m-ECT). Unfortunately, no studies have ever directly addressed what to do after a successful course of ECT. Therefore, we’ll have to extrapolate from the current research to figure out what the most appropriate course of action might be. Do patients who respond to ECT even need maintenance treatment? Do medications help reduce the risk of relapse? Lithium has long been touted as the best choice post-ECT. Is this just because it was the first treatment on the block, or is it truly better? Are some antidepressants better than others? How does m-ECT compare with medications? Is the combination of medications and m-ECT better than either alone? Can we expect ECT to work again if the patient responded to it in the past? Can psychotherapy prevent post-ECT relapse? Table: Preventative Steps After Successful ECT Knowing the high rates of relapse, you discuss with Juan the post-ECT plans even before making the referral for ECT. You explain that the best option is the combination of m-ECT plus medications; over time, m-ECT can work even when given as infrequently as every 3 months. “Rescue” ECT can also be used if his mood starts to dip. Regarding Juan’s specific medication regimen, you recommend staying on escitalopram but stopping the aripiprazole due to its lack of demonstrated efficacy and its risk of long-term side effects, many of which are worse for older patients like him. You recommend lithium as the best option if he wants additional medication protection. You also strongly encourage him to connect with a psychotherapist. TCPR Verdict: ECT works great for depression, but the relapse rates are high in the months following treatment. Start the preventative discussion before your patient undergoes ECT, and consider: 1) Maintenance ECT, 2) An antidepressant with lithium augmentation, and 3) Psychotherapy.

Absolutely. Here, the data are unequivocal. Without treatment, around 80% of patients who recover with ECT will go right back into their depression within 6 months. In the most rigorous study, 21 of 25 patients (84%) who responded to ECT and were randomized to placebo relapsed within 6 months (Sackeim HA et al, JAMA 2001;285(10):1299–1307). That figure is backed up by a meta-analysis that found relapse rates on placebo of approximately 80% after 6 months (Jelovac A et al, Neuropsychopharmacology 2013;38(12):2467–2474). That’s about twice the relapse rate seen with some of the preventative treatments I’ll discuss below.

Yes. A meta-analysis of seven studies (n = 402) found that medications cut the risk of relapse in half at the 6-month mark (Jelovac et al, 2013). The bad news is that even with treatment, about 50% of patients relapse within 6 months. One medication strategy stands out from the rest, however: lithium augmentation.

Lithium does have protective effects after ECT when used to augment an antidepressant. The landmark Sackeim study found relapse rates of 39% on nortriptyline with lithium, compared to 60% on nortriptyline alone (n = 55) (Sackeim et al, 2001). A naturalistic, retrospective study looking at a Swedish registry found that patients receiving lithium post-ECT had significantly lower relapse rates, while those receiving antipsychotic medications for depression had an elevated risk (n = 486) (Nordenskjöld A et al, Depress Res Treat 2011;2011:470985). Finally, a recent meta-analysis of 14 studies found that patients receiving lithium were about 50% less likely to relapse than patients receiving maintenance regimens that did not include lithium (n = 9748) (Lambrichts S et al, Acta Psychiatr Scand 2021;143(4):294–306).

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have long been the gold standard, but unlike lithium, this appears to be more a function of being first on the block. Prudic and colleagues, for example, found that venlafaxine + lithium (n = 63) was just as effective for prevention of relapse post-ECT as nortriptyline + lithium (n = 59) (Prudic J et al, J ECT 2013;29(1):3–12). Although SSRIs have been much less studied than TCAs, the research to date suggests they are no less effective (Jelovac et al, 2013).

A meta-analysis across four studies (n = 146) showed that m-ECT clearly works, with reported relapse rates at 6 months of just under 40% (Jelovac et al, 2013). In comparing m-ECT to medications, Kellner and colleagues found no statistical difference in 6-month relapse rates between patients randomized to m-ECT (n = 89; 37%) and those randomized to maintenance antidepressant therapy (n = 95; 32%) (Kellner CH et al, Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63(12):1337–1344). Although no studies to date have ever found m-ECT inferior to pharmacotherapy, a recent meta-analysis concluded that “there is little evidence to support superior efficacy of m-ECT over maintenance pharmacotherapy” (Elias A et al, J ECT 2019;35(2):91–94).

The combination appears to be better. Nordenskjöld and colleagues randomized 61 patients to receive m-ECT + pharmacotherapy or pharmacotherapy alone over the course of a year, and found that only 32% relapsed with combination treatment compared to 61% with medications alone (p = 0.04) (Nordenskjöld A et al, J ECT 2013;29(2):86–92). In a literature review on the topic, Brown and colleagues concluded that combination therapy has consistently outperformed medications alone, and a recent large-scale study by Kellner and colleagues further bolstered this conclusion (Brown ED et al, J ECT 2014;30(3):195–202; Kellner CH et al, Am J Psychiatry 2016;173(11):1101–1109).

This is an important question since many patients would prefer to forgo m-ECT if they were confident that a second course of ECT, if needed, would work. Unfortunately, this question has never been studied. Lacking evidence, it would be a mistake to assume ECT will work again.

Even if psychotherapy did not work during the acute phase of a severe depression, it might still help prevent relapse after a successful course of ECT. Brakemeier and colleagues randomized patients who had responded to ECT to receive either medications alone (n = 18), medications + m-ECT (n = 25), or medications + cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT; n = 17) (Brakemeier E et al, Biol Psychiatry 2014;76(3):194–202). The sustained response rate for the meds + CBT group was 65%—-much higher than the response rates for meds alone (33%) or meds + m-ECT (28%).![]() To learn more, listen to our 8/30/21 podcast, “How to Use Nortriptyline.” Search for “Carlat” on your podcast store.

To learn more, listen to our 8/30/21 podcast, “How to Use Nortriptyline.” Search for “Carlat” on your podcast store.