How to Diagnose ADHD in Bipolar Disorder

The Carlat Psychiatry Report, Volume 19, Number 10, October 2021

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/tcprv19n10/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: ADHD | ADHD Rating Scale-5 | Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder | Bipolar Disorder | Bipolar II | Comorbidity | Diagnosis | Diagnostic Testing | Hypomania | Psychiatric interviewing

Chris Aiken, MD.

Editor-in-Chief of TCPR. Practicing psychiatrist, Winston-Salem, NC.

Dr. Aiken has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Hailey is a 24-year-old woman with bipolar II disorder who has recently come out of a mixed episode. Although her mood symptoms have resolved, she is distracted easily, has difficulty organizing her work, and often forgets important tasks. She read about ADHD online and asks if she can have a stimulant to help her focus.

ADHD and hypomania share many symptoms in common: distraction, hyperactivity, impulsivity, irritability, and excessive talking. In theory these symptoms are episodic in bipolar disorder and continuous in ADHD, but in practice that separation is not so clean. In this article I’ll present a more nuanced guide to this vexing diagnosis.

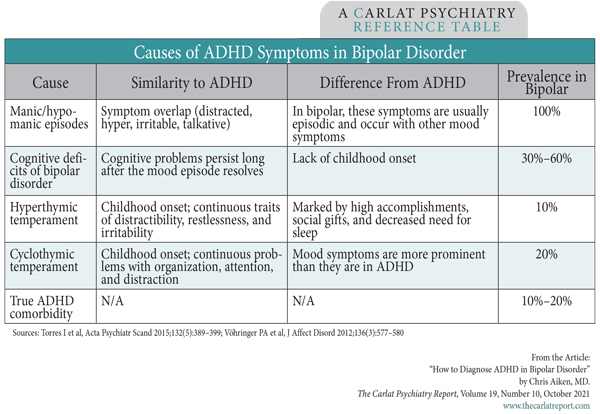

ADHD and bipolar disorder can genuinely occur together, and they do so in 10%–20% of bipolar patients. But bipolar disorder can also cause symptoms that mimic ADHD, which is why 30%–50% of bipolar patients who screen positive for ADHD on a self-reported questionnaire do not turn out to have ADHD after a structured interview (Torres I et al, Acta Psychiatr Scand 2015;132(5):389–399).

The table below lists four ways that bipolar disorder can mimic ADHD, starting with the manic or hypomanic episodes themselves. These episodes are relatively easy to distinguish from ADHD by their episodic nature and lack of early childhood onset. A more difficult rule-out is persistent cognitive dysfunction due to the neuroprogression of bipolar disorder itself. Each episode in bipolar disorder can take a toll on the brain, causing ADHD-like symptoms of inattention, disorganization, and executive dysfunction. Unlike ADHD, these cases are marked by memory problems and mental slowing, and they usually lack the restless, frenetic energy of ADHD. More importantly, these cognitive deficits follow an opposite course to ADHD. They start in adulthood and worsen with time, while ADHD begins before age 12 and tends to improve in adulthood.

Table: Causes of ADHD Symptoms in Bipolar Disorder

The affective temperaments

Hypomanic symptoms are sometimes woven into the patient’s temperament in ways that resemble ADHD. Compared to unipolar patients, patients with bipolar disorder have high levels of inattention, restlessness, and excessive daydreaming when they are not in an episode (Akiskal HS et al, Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995;52(2):114–123; Clark L et al, Biol Psychiatry 2005;57(2):183–187). Like ADHD, these traits have a childhood onset and a continuous course, making it very difficult to tease the two apart.

Temperamental differences have been recognized in bipolar patients for over 100 years, and they are generally clustered into four categories: dysthymic, hyperthymic, cyclothymic, and irritable. The affective temperaments that most resemble ADHD are the hyperthymic (ie, hypomanic traits) and cyclothymic (frequent alterations between hypomanic and depressive traits).

Hyperthymic patients often present because they lack patience and attention during tedious tasks. Like patients with ADHD, they are physically restless, become easily distracted, and tend to talk over others. What sets them apart from ADHD patients is their high level of accomplishment and decreased need for sleep. These patients are driven, and that drive has a focus that propels them to success in the working world, where they often rise to leadership positions.

The cyclothymic temperament is marked by unpredictable shifts from energized to sluggish, extroverted to withdrawn, passionate to disinterested. The result is inconsistent work performance, disorganization, and a lack of focus that can look just like ADHD. In theory, mood symptoms like lability, irritability, depression, and insomnia should distinguish this temperament from ADHD, but telling them apart is not so easy because these affective traits are also common in ADHD (Ozdemiroglu F et al, Psychiatry Investig 2018;15(3):266–271).

A quick way to learn about these temperaments is to read the TEMPS-A, a self-report questionnaire that captures the hallmark features of each type. This scale is the gold standard for evaluation of the affective temperaments and is available at www.psychiatryletter.net. Patients circle the statements on the questionnaire that apply to them. For cyclothymic, those include “I constantly switch between being lively and sluggish” and the ADHD-like “I often start things and then lose interest before finishing them.” For hyperthymic, they include “I am totally comfortable even with people I hardly know” and the ADHD-like “I am always on the go.”

Putting it all together

When an adult with bipolar disorder presents with ADHD-like symptoms, use the following steps to figure out the cause:

- Wait until their mood episodes have resolved for 4–6 months before assessing for ADHD.

- Assess for childhood onset of ADHD before age 12 to rule out cognitive deficits from the progression of bipolar disorder.

- Rule out other causes of cognitive problems like substance use, sleep deprivation, traumatic brain injury, and medical illnesses (eg, sleep apnea, hypothyroidism, cerebrovascular disease, recent infection).

- Look for signs of lifelong affective temperaments that might better explain the symptoms.

- Carefully assess for ADHD with the DSM-5 criteria, preferably using a structured interview.

A structured interview will help filter out some of the symptomatic mimicry that confuses the picture. It sounds cumbersome, but it’s not. These instruments simply translate the DSM criteria into questions like “Do you often have difficulty sustaining your attention in tasks? And how was that in your childhood?” The DIVA-5 is a good option for ADHD (www.divacenter.eu, $12 one-time fee). Two others covering a wider array of psychiatric disorders are the MINI-7.0 (www.harmresearch.org, $10 plus a per-use fee) and Abraham Nussbaum’s Pocket Guide to the DSM-5 Diagnostic Exam (Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013).

Those steps do a pretty good job of ruling out other causes of ADHD, but one problem remains. What if your patient meets the full DSM-5 criteria for ADHD and also has a prominent affective temperament? We don’t have a good way to tease those apart, so it’s best to proceed gingerly with treatment, starting with medications for ADHD that have a low risk of causing mania (eg, clonidine or guanfacine). I’ll get into that more in a future article on treating ADHD in patients with bipolar disorder.

TCPR Verdict: Cognitive symptoms are common in bipolar disorder, even after the mood episodes have resolved. Common causes include cognitive deficits from the progression of mood episodes, affective temperaments like cyclothymic or hyperthymic, or a genuine comorbidity with ADHD. A detailed history and some structured testing can clarify the cause.

![]() For a guide to nonpharmcologic ways to improve cognition, search for “Pocket Psychiatrist” (our patient edition) on your podcast store and scroll to the 5/3/21 episode.

For a guide to nonpharmcologic ways to improve cognition, search for “Pocket Psychiatrist” (our patient edition) on your podcast store and scroll to the 5/3/21 episode.