A Primer on Vaping: 15 Years On

The Carlat Addiction Treatment Report, Volume 10, Number 1, January 2022

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/catrv10n1/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: E-Cigarettes | Smoking Cessation | teens | Vaping

Sivabalaji Kaliamurthy, MD

Sivabalaji Kaliamurthy, MD

Attending psychiatrist, Children’s National Medical Hospital, Washington, DC.

Dr. Kaliamurthy has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

CATR: Can you give us your professional background?

Dr. Kaliamurthy: I finished medical school in India followed by an adult psychiatry residency and child psychiatry fellowship at the Institute of Living in Hartford, CT. I then completed an addiction psychiatry fellowship at Yale and am currently an attending psychiatrist at the Children’s National Medical Hospital in Washington, DC.

CATR: And vaping has been a particular area of interest for you.

Dr. Kaliamurthy: Yes, my interest got started at an addiction-related conference in 2016. I noticed attendees going outside between talks to use these big devices to blow plumes of smoke. I’m a bit of a technophile, so I started to learn about them on my own. During my child fellowship, I saw a huge prevalence of vaping among adolescents. Kids being admitted to the hospital would go into nicotine withdrawal, which used to be uncommon. Then in my work at an opioid treatment program, many of my adult patients were switching from combustible cigarettes to vapes.

CATR: What should providers know in terms of how these devices function?

Dr. Kaliamurthy: It’s helpful to know the basics so you can understand how patients use and modify these devices, and what some consequences might be. There are a wide variety of products, but all have the same basic components: 1) a battery, which can be rechargeable or disposable; 2) an atomizer, or heating coil, that vaporizes the nicotine; 3) the nicotine source or “e-juice”; and 4) aerosol, the product emitted by the device and inhaled into the lungs. You’ll hear the words “cartridge” or “pod” as well, which refers to a self-contained unit that may have the liquid and the atomizer together or is sometimes just an e-juice container.

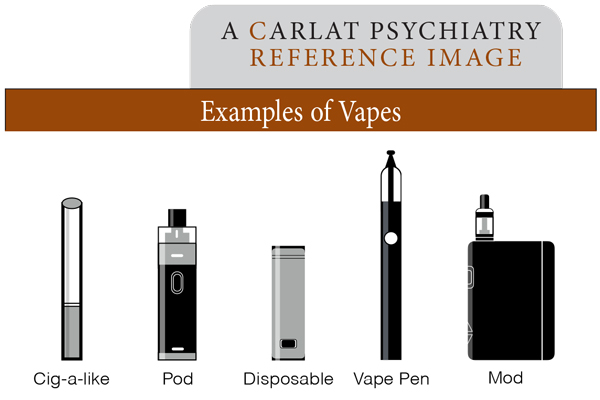

Image: Examples of Vapes

CATR: And how are these components combined to make different devices?

Dr. Kaliamurthy: For research and clinical purposes, we can classify these devices as “open system” and “closed system.” Closed-system products are self-contained units in which the manufacturer predetermines every aspect of the device: battery, power, atomizer, and e-juice. The first closed-system devices were available as early as 2007. They look like traditional cigarettes and are sometimes called “cig-a-likes.” There are other more recent closed-system devices that are pod-based; some look like pen drives and others are simple small disposable devices. The open-system devices offer a lot more flexibility to the users. They can change the battery settings, resistance on the atomizer coils, e-juice concentrations, etc. These devices come in different shapes and sizes as well. Devices called “vape pens” look like cylinders with a few interchangeable parts. The more common open-system devices are entirely customizable. These are called “mods” (which stands for modifications) and look like big tanks (see figure above).

CATR: Open-system devices must make it tough to know exactly what a patient is using.

Dr. Kaliamurthy: Yes. New products come out nearly every day, many from small companies, but big tobacco is changing the landscape even further. And some of these companies are clearly targeting children by making devices that are easily concealable. For instance, there was a company creating hoodies where the string around the hood could be put in the mouth and had an e-cigarette device attached! Some flavorings are also clearly being marketed toward the younger generation, which the FDA has begun clamping down on. There are flavors with names like “unicorn puke” or “hulk tears.” You hear a name like that and think, “Why would an adult buy a product called unicorn puke?”

CATR: And what should we know about the e-juice?

Dr. Kaliamurthy: E-juice predominantly contains either propylene glycol or vegetable glycerin, as well as nicotine. In closed-system devices, the manufacturer determines all the e-juice components. In open-system devices, users can assemble their own e-juice. They can buy the vegetable glycerin or propylene glycol, nicotine concentrate, flavorants, and mix them together however they want. The nicotine itself is always derived from tobacco but is available in two forms: free-base nicotine (the naturally occurring, non-dissolvable form of nicotine) or soluble nicotine salts, which companies began developing about five years ago. Studies showed that, compared to a regular cigarette, salts result in a higher blood-nicotine concentration that then decreases at a faster rate (www.classaction.org/media/colgate-et-al-v-juul-labs-inc-et-al.pdf, Page 19, Figure 4, Juul patent filing). The result is a rapid upward spike in blood nicotine followed by a rapid decline. And we know there is more addictive potential in substances that cause rapid euphoric effects, then leave to quickly create a negative affective state.

CATR: You mentioned flavorants.

Dr. Kaliamurthy: Yes. There is a multitude of flavors out there, and new ones come out all the time. Early studies show that added flavors increase dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens (Kroemer NB et al, Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2018;28(10):1089–1102). The sweeter the flavor, the bigger that dopaminergic response, which we hypothesize means higher addictive potential. And each flavor confers its own risk in terms of the final aerosol that’s produced. We have studies showing that cinnamon and menthol in particular can be cytotoxic to stem cells (Lee WH et al, J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73(21):2722–2737). With flavor compositions constantly changing, it can be hard to offer a sound clinical opinion to patients about specific flavors.

CATR: Can you tell us some of the ways in which open-system devices are modified?

Dr. Kaliamurthy: A common one is called “dripping,” in which e-juice is dropped directly onto an exposed heating coil to produce vapor that is then inhaled. Coils can be removed from devices or purchased separately as an “RDA,” which stands for rebuildable dripping atomizer. Anecdotally, patients tell me that dripping produces a more flavorful vapor, plus more euphoric effects if the liquid contains cannabis (in which case the term “dabbing” is often used instead of dripping). Modifications to increase smoke volume are popular among the “smoke trick” community in which people blow smoke into unusual shapes. Atomizers are electrical heating elements, so people disassemble devices to increase the electrical resistance, which produces more heat and vapor. But these higher temperatures result in aerosol containing metals from the heating element itself. The higher temperature changes the chemical composition of the aerosol, potentially producing toxic combustion products.

CATR: Do you ever recommend vaping to quit smoking combustible tobacco?

Dr. Kaliamurthy: Never as a first-line treatment. It comes down to the patient’s goals: Do they want to quit nicotine completely or just quit combustible cigarettes? If the goal is to quit smoking altogether, I tell them about evidence-based treatments and recommend that they try those first, because they have the most evidence. But I also tell them at the end of the day, it is their choice, and if they decide to vape, I provide psychoeducation.

CATR: What sort of information do you give your patients?

Dr. Kaliamurthy: I advise that they stick to simple devices from established manufacturers and not to modify them, which can lead to unknown harms. I also educate patients about nicotine from cigarettes versus vaping. For example, one cigarette contains about 10 mg of nicotine, so a pack of 20 has 200 mg. Patients may think that a 50 mg pod is cutting down compared to that pack of cigarettes—but that’s not necessarily accurate. Cigarettes have a nicotine bioavailability of about 10%, so only 20 mg of nicotine per pack ends up in the bloodstream (Benowitz NL et al, Handb Exp Pharmacol 2009;(192):29–60). Depending on the form of nicotine in the e-juice, much more than 20 mg of nicotine per pod may find its way into the patient’s bloodstream. So, I recommend to always start at a lower dose and only increase if they feel cravings. I’ve seen patients switch from cigarettes to vaping in order to quit smoking and go back to cigarettes for one reason or another, and end up smoking more cigarettes than ever before because they now need more nicotine.

CATR: What do you say to patients who are attracted to vaping because it’s trendy, as opposed to traditional cigarette smoking?

Dr. Kaliamurthy: I warn patients against “artisanal” vaping, especially the young adults. By artisanal I mean the burgeoning subculture that treats vaping as a hobby, with fancy expensive accessories. It creates a gamification of smoking beyond a simple nicotine delivery system. Not only can it get expensive, but it can lead to high levels of nicotine consumption as well.

CATR: Are there immediate dangers of vaping that patients need to be aware of?

Dr. Kaliamurthy: One is nicotine toxicity, which can happen to inexperienced patients using these high-nicotine products. Initially, nicotine toxicity has stimulatory effects like tachycardia, hypertension, anxiety, GI distress, and can even cause seizures. After the stimulatory effects, patients experience sedation, hypotension, and bradycardia. In severe cases, this later phase can lead to neuromuscular blockade and coma. This level of toxicity is rare from vaping, but can certainly happen if kids get into e-juice and drink it, so safe storage is very important. Treatment is mostly supportive, and patients really need to be treated in a hospital setting. Another danger is that there are cases of batteries catching fire or bursting, causing facial injuries (Jones CD et al, Burns 2019;45(4):763–771). Batteries are more likely to malfunction if they are charged often or overnight, or if they overheat. Patients should stop using the devices if they become hot to the touch and always charge them according to instructions. We don’t know for sure, but it’s probably more likely for batteries to malfunction in open-system modified devices than closed-system devices manufactured by large companies.

CATR: Is there good evidence that vaping products can help patients quit smoking?

Dr. Kaliamurthy: A little. Most evidence comes from the UK’s National Health Service. They collected data and published it in a high-profile study that generated a lot of interest (Hajek P et al, N Engl J Med 2019;380(7):629–637). The exciting finding was that when patients switched from combustible cigarettes to vaping, at the end of one year most patients had stopped using combustible cigarettes altogether. That finding got lots of fanfare; however, most of the patients were still vaping at the end of the study. Patients did get off combustible tobacco, but they were still using nicotine, possibly in equal or higher doses than before. So, it’s difficult to use this study to say whether or not vaping should be recommended as a way to quit smoking. And, unlike the US, the UK has a highly regulated vaping product environment. This raises the question of generalizability of this study outside of the UK, especially in the US where there is not nearly the same level of regulation.

CATR: How do you view switching from cigarettes to vaping from the standpoint of harm reduction?

Dr. Kaliamurthy: The US system is very unregulated, so it’s difficult to know long-term risks. We have known about the harms of tobacco for decades, so with vaping we are still very much catching up. There is evidence that, at least over the short to medium term, the harms from vaping are less than that of combustible tobacco products (Kmietowicz Z, BMJ 2018;363:k5429). And anecdotally, patients tell me that they are able to breathe better, so subjectively there are improvements in physical health, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t any harm.

CATR: You mentioned THC and cannabis products being vaped. Are there differences between vaping cannabis and vaping nicotine?

Dr. Kaliamurthy: Not a lot. Any device used to vape nicotine can be used to vape cannabis. These products are available in both medical and recreational dispensaries, as well as on the streets.

CATR: What should clinicians pay attention to if their patients are vaping cannabis?

Dr. Kaliamurthy: I have noticed vaping cannabis is especially popular in adolescents because it is so easily concealable. The paraphernalia is easy to hide and the smoke it emits can be low in volume and less odorous, making it easier to vape THC without facing consequences at school and at home. Another concern is the move toward using cannabis concentrates, which can have THC concentrations over 80%. Some people might seek out high-concentrate products believing that it will result in the use of less cannabis overall. However, a recent study showed that THC blood levels were significantly higher in patients who consumed cannabis by vaping concentrates versus smoking (Bidwell LC et al, JAMA Psychiatry 2020;77(8):787–796).

CATR: Vaping THC has been associated with serious lung injury.

Dr. Kaliamurthy: Yes, E-cigarette, or Vaping, product use Associated Lung Injury (EVALI) was a big concern. We saw a rapid uptick in patients presenting with lung injury in August 2019, it peaked in September, and there was a downward trend after that. These patients’ injuries had no underlying cause except a recent history of vaping. There was no single ingredient identified as causing EVALI, though in the majority of cases people had used a vape for THC containing vitamin E acetate in the cartridge and bought on the streets, not from a dispensary. It is possible that EVALI is associated with a particular type of device sold on the street under the name “dank vapes,” but this is still unclear. The CDC tracked approximately 3,000 total cases with 68 deaths as of February 2020, but we don’t have updated data since then (www.tinyurl.com/zmcevyhu). Geography plays a role too; most cases were in Texas and Illinois, followed by California and New York. Since COVID, however, we really haven’t been doing a good job of tracking these cases.

CATR: With the limited information available, what advice would you give to a patient vaping THC?

Dr. Kaliamurthy: The CDC says that the only way to definitively avoid vaping-associated lung injury is to not use these devices at all. But if patients are going to vape THC, I recommend that they not use products obtained off the street. I always encourage patients to avoid sources that they don’t know and to get devices from dispensaries if possible.

CATR: Do you have recommendations on how providers might keep up with this rapidly evolving field?

Dr. Kaliamurthy: There’s a lot of information on the FDA and CDC websites. The American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry and American Academy of Pediatrics have good informational websites as well (www.tinyurl.com/ne6pdjvm; www.tinyurl.com/mua9r3ay). Unfortunately, there aren’t many established resources.

CATR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Kaliamurthy.