Alcohol-Induced Liver Disease

The Carlat Addiction Treatment Report, Volume 10, Number 2&3, March 2022

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/catrv10n2-3/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Alcohol related liver disease | Alcohol use disorder | Laboratory Testing in Psychiatry

Ramon Bataller, MD

Ramon Bataller, MD

Chief of Hepatology, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA.

Dr. Bataller has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

CATR: Many non-specialists find the jargon of the liver field confusing. Can we start by reviewing the relevant terminology that clinicians should be familiar with?

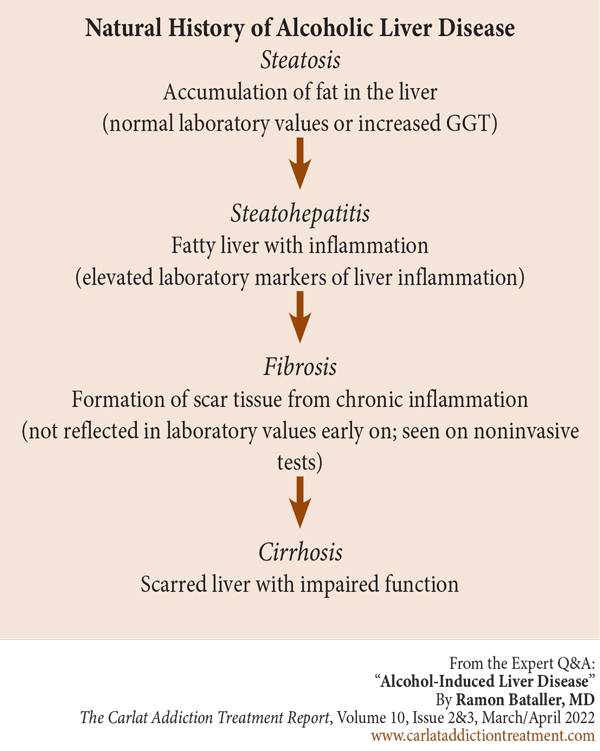

Dr. Bataller: The best way to do that is by reviewing the natural history of alcohol-related liver disease. Most people who drink excessively accumulate fat in the liver; this is an early stage of disease called steatosis. This fat can develop inflammation, which is called steatohepatitis. Over time, steatohepatitis results in scar tissue deposition called fibrosis. Early on, fibrosis itself is asymptomatic and can only be seen with imaging or biopsy. Cirrhosis is when the fibrosis becomes extensive enough that it impairs liver function. That is the natural history of chronic liver disease (Editor’s note: See figure below). Patients who drink heavily can develop an acute medical condition called alcoholic hepatitis, which is a rapid form of liver failure often characterized by jaundice and ascites. It is increasingly seen in young women, who are especially vulnerable to this condition, and has a mortality as high as 25% in one month and greater than 50% over five years (Hosseini N et al, Alcohol and Alcoholism 2009;54(4):408–416).

Image: Natural History of Alcoholic Liver Disease

CATR: In other words, early detection is key.

Dr. Bataller: Absolutely. A big problem in the field is the focus on advanced disease instead of prevention or early detection. To make an analogy, it’s as if the colon cancer field were only focused on metastatic disease. Of course, we know that routinely performing colonoscopies for patients older than 45 can identify early cancers and precancerous growths. We need to have the same approach in patients with excessive drinking.

CATR: What should clinicians be focusing on with their patients in the office?

Dr. Bataller: The number one thing is to identify people who drink heavily, and alcohol is so often underreported. Sometimes it’s for job security or health insurance, but usually it’s stigma or shame. So, a gentle non-judgmental approach is critical. First, very simply, you need to sit with your patients. You need to devote time. That goes a long way in building trust. I’ve found that educating patients about the genetic contribution to alcohol use disorder (AUD) can be helpful too. I ask about first-degree relatives with problematic drinking, and most patients who drink also have family members who drink. If so, I say, “This is not your fault. Your genes make you more vulnerable to alcohol problems, and this is the case with many of my patients, but we can work to solve this together.” This can be helpful especially for patients who might have lost a job or personal relationships because of alcohol; there can be a lot of self-blame, and this approach can give some relief.

CATR: Are there specific techniques that you find useful?

Dr. Bataller: There are two simple techniques that I learned working with addiction therapists over the years. The first is “overshooting.” Rather than asking, “How many drinks do you have each day?” I’ll ask, “How many drinks do you have a day—10 to 15?” In response, the patient may say, “Oh, no, I only have five.” Likewise, I’ll ask, “Was your last drink yesterday or a week ago?” They’ll say, “No, doctor, it was two weeks ago.” The other technique is asking about withdrawal symptoms. If I suspect that a patient drinks a lot, but they are not forthcoming, I’ll ask, “If you stopped drinking 100% now—not a single sip—will you start shaking? Will you start sweating and vomiting?” If the patient says yes, then I know two things: 1) that patient is a heavy drinker, and 2) they need detox in order to be able to reach total abstinence.

CATR: What else should clinicians be looking for specifically related to alcohol-induced liver disease?

Dr. Bataller: A good physical exam can be very revealing. We learn all about the signs in medical school, yet we often don’t look for them in actual clinical practice. Hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and ascites are physical signs that can give you a good idea of the patient’s liver status. Clinicians should examine for these. As a hepatologist, I perform thorough physical exams on all my patients, though I understand that some psychiatrists do not routinely do them outside of the emergency department or specialty clinic settings. Even so, you can pick up other important signs just through observation. A keen eye can pick up spider angioma, gynecomastia, and palmar erythema as long as you are looking for them. Jaundice can be seen anywhere on the skin, but pay particular attention to the inside of the eyelids.

CATR: And what about labs? Many non-experts look at alanine and aspartate transaminase (ALT and AST), maybe bilirubin, and that’s it. Can you walk us through the liver function tests?

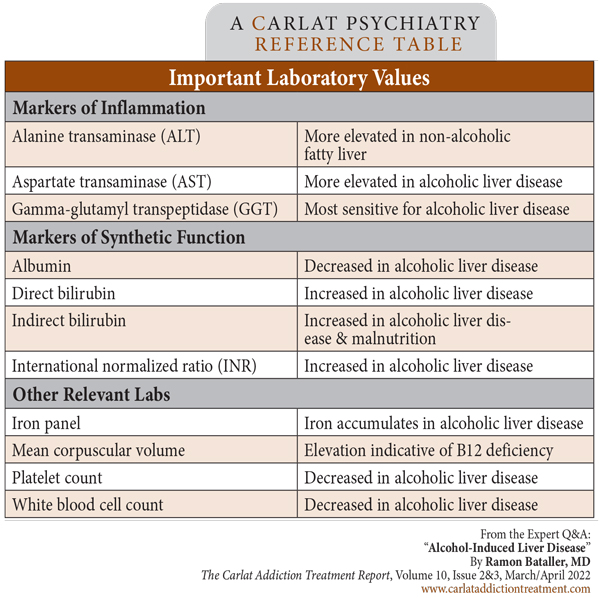

Dr. Bataller: Well, ALT and AST are important. They become elevated from direct hepatocyte injury and inflammation. Typically, ALT is more elevated in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and AST is higher in alcohol-related liver disease. Increased bilirubin, increased international normalized ratio (INR), and decreased albumin reflect liver failure, a more advanced stage of liver disease. Mild elevations in ALT and AST (less than five times normal) do not necessarily imply liver dysfunction, and it is not necessary to adjust doses or hold hepatically metabolized medications. Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) is ordered less often but is more sensitive in detecting liver damage from alcohol. You usually see levels eight or 10 times normal in patients who drink heavily. There are also hematologic abnormalities with certain patterns suggesting heavy alcohol use: low platelets and white blood cells from bone marrow toxicity, and macrocytic anemia from B12 deficiency. You can also see elevated iron; interestingly, I sometimes get consults for hemochromatosis, but it turns out the patients actually have AUD. Transferrin is an enzyme that is involved in maintaining iron balance, and carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT) is elevated in patients who drink heavily. You can order this as a separate lab test, but I don’t order it frequently because it doesn’t provide information that the other tests don’t already reveal.

CATR: What about bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase?

Dr. Bataller: Bilirubin starts as unconjugated and is a natural product of hemoglobin breakdown. It is measured as indirect bilirubin. This goes to the liver, where it is conjugated so that it can be excreted. That’s measured as direct bilirubin. Typically, both are elevated in people with liver failure from alcohol. Alkaline phosphatase can be elevated for many reasons, but for our purposes, it is a marker of bile flow. Obstruction from a stone or cancer will increase the level. It’s minimally elevated in alcoholic liver disease, and only gets very high when liver damage is in an advanced stage and causes the liver to become dysmorphic and inflamed.

CATR: We hear about synthetic function. What does that mean and why is it important?

Dr. Bataller: So far, the labs we’ve talked about measure liver damage. But equally important is how well the hepatocytes are functioning. That’s what we mean when we say “synthetic function.” Because unconjugated bilirubin is produced constantly by the body, and the liver actively converts it into conjugated bilirubin, both direct and indirect bilirubin measurements are indicators of the synthetic function of the liver. In fact, of all the markers of synthetic function, bilirubin has the greatest predictive value of mortality in patients with alcohol-induced liver disease (Parker R et al, Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;S1542-3565(21)00092-6). If a patient with elevated bilirubin is able to stop drinking, and their bilirubin level drops back to normal, that means their liver’s synthetic function has returned, and that patient has a good prognosis. If a patient’s bilirubin keeps increasing even during abstinence, that means the liver’s synthetic function has been permanently impaired, and that results in a very poor prognosis; their mortality is more than 50% at three months.

CATR: Should we be aware of any other measures of synthetic function?

Dr. Bataller: Other measures of synthetic function are the proteins that the liver makes. One of the main ones is albumin, which makes up about half of all the circulating protein in the blood, and its production can be impaired in patients with cirrhosis. Since it is so abundant, albumin is one of the main determinants of intravascular oncotic pressure; therefore, low albumin levels can result in capillary leak and contribute to ascites accumulation. The liver also makes clotting factors, so people with impaired synthetic function have an elevated INR. Patients with advanced cirrhosis can have very high bleeding risk.

CATR: Of all these labs, which would you recommend that mental health providers order for screening purposes?

Dr. Bataller: Every patient seen with AUD or excessive alcohol intake should be checked with ALT, AST, GGT, bilirubin, an iron panel, albumin, coags, and a complete blood count. In patients with known liver disease, clinicians can estimate the degree of liver scarring using routine lab values (Moreno C et al, J Hepatol 2019;70(2):273–283). I recommend the FIB-4 Index, which estimates the amount of scarring in the liver using the patient’s age, platelet count, and ALT/AST values. It is important to calculate the amount of scarring if you are considering starting a medication like disulfiram, which can cause liver failure in patients with advanced fibrosis. Avoid disulfiram in patients with a FIB-4 score of 5 or above, and be very cautious if the score is above 2. (Editor’s note: See “Important Laboratory Values” table below.)

CATR: What about naltrexone dosing?

Dr. Bataller: Believe it or not, there has never been a clinical trial of naltrexone in patients with alcohol-related liver disease. Naltrexone can be an effective medication, but it comes with three red flags:

1) It can cause hepatotoxicity, less so than disulfiram, but I don’t recommend it for patients with liver failure;

2) At least anecdotally, it can cause encephalopathy, especially in people with cirrhosis; and

3) It can precipitate opioid withdrawal if patients have any opioids in their system.

So, clinicians should be careful with naltrexone in patients with opioid use disorder (OUD). Of course, naltrexone isn’t contraindicated in patients with OUD, and the injectable form is actually an approved OUD treatment, but clinicians should just be cautious.

CATR: What lab values are important to consider when prescribing naltrexone?

Dr. Bataller: Avoid naltrexone if transaminases are very high, five times the upper limit of normal. But if that is the case, there is usually more going on than just heavy drinking. More important are the synthetic markers we discussed before: bilirubin, albumin, and INR. There are no studies or established protocols here, so this is an expert opinion, but I would not give naltrexone to patients with total bilirubin greater than 3 or INR greater than 1.5. That indicates synthetic dysfunction and risks further hepatotoxicity. That being said, naltrexone can be cautiously considered in these patients as long as they are monitored carefully. I’ve taken this risk and succeeded in a few cases.

Table: Important Laboratory Values

CATR: Do you adjust the dose for these patients?

Dr. Bataller: Again, there is no evidence base, but I start with 50% of the dose in patients with impaired synthetic function. That is, if I decide to use naltrexone at all.

CATR: We’ve discussed disulfiram and naltrexone. What about other medications for AUD in patients with liver disease?

Dr. Bataller: Acamprosate is the only one left that is FDA approved. But there are others with varying amounts of evidence: gabapentin, baclofen, and topiramate. These all seem to be safe. For an overview, I recommend a review article I co-wrote discussing these medications in the setting of alcoholic liver disease (Arab JP et al, Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;19(1):45–59).

CATR: How does comorbid viral hepatitis affect all this?

Dr. Bataller: Well, it makes everything worse, as you might imagine. The laboratory monitoring that we discussed is the same, whether you are talking about alcoholic liver disease or viral hepatitis. Obesity increases fat deposition in the liver as well and accelerates disease progression. Of course, research studies try to isolate causes of disease and treatments, but in real life, comorbidity is common. We may treat hepatitis C (HCV), but if the patient is still drinking heavily, their liver disease won’t get any better. So, we need to treat comorbidities; we have to be holistic and inclusive.

CATR: Would you treat HCV in a patient who is actively drinking?

Dr. Bataller: That is a very good question, and different providers will answer differently. For me, it’s an ethical issue, and I say yes. I always say, “You’re not a judge; you’re not a police officer; you’re not a priest. You’re a doctor.” So, if your patient might benefit from HCV treatment, you should advocate for it; many people will improve if their HCV is cured. People who continue to drink heavily are likely to still have active liver disease even after treating HCV, but as physicians, we have a mission to protect public health as well. Alcohol use also increases risky sexual behavior, drug use, and needle sharing. So, treating HCV in patients who continue to drink protects the public as well.

CATR: And finally, when should mental health and addiction providers consider expert hepatology consultation?

Dr. Bataller: First of all, we should be working together much more. We work in silos, but of course the patient’s organ systems are all connected and affect one another. Ideally, every addiction center should have a hepatologist linked to it. But more generally, early detection of disease and referral is best. Review the labs we talked about earlier, and consider making a referral to a hepatologist at any sign of underlying cirrhosis, liver failure as indicated by impaired synthetic function, or clinically obvious jaundice.

CATR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Bataller.