Breastfeeding and Addiction

The Carlat Addiction Treatment Report, Volume 9, Number 4&5, July 2021

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/addiction-in-pregnancy-july-august/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Breastfeeding | childcare | Free Articles | infant | lactation | newborn

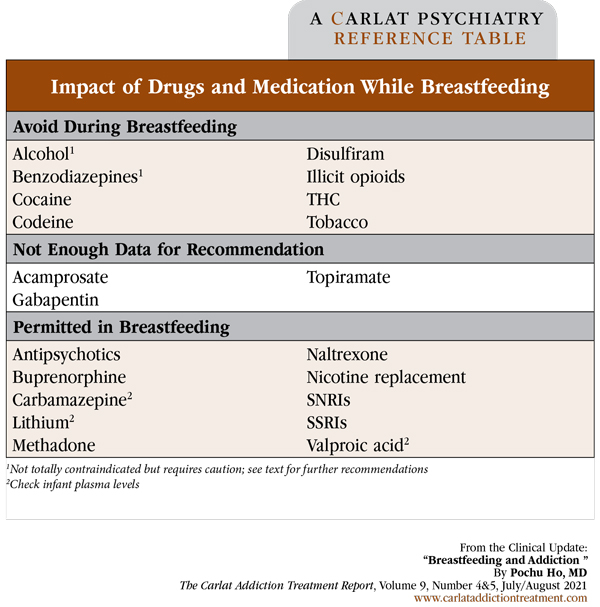

Pochu Ho, MD. Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, Yale University. Director of Psychiatric Consultation Service, West Haven VA Medical Center, CT. Dr. Ho has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity. Addiction providers typically treat one patient at a time. But once we start working with a patient who is breastfeeding, that number jumps to two (or more in the case of twins, triplets, etc). Although breastfeeding has a host of infant health benefits, many providers do not feel confident managing patients who are nursing. In order to deliver the best care to these patients, providers need to be aware of how substances find their way into breast milk, how to discuss commonly misused substances, and which medications are safe to prescribe. Bioavailability in breast milk Properties of substances Maternal factors Infant factors Substances and breastfeeding Alcohol Opioids Cocaine Cannabis Tobacco Medications for addiction and breastfeeding In terms of medication for alcohol use disorder (AUD), disulfiram passes into breast milk and therefore is not recommended for breastfeeding (Fenner S. Safety in lactation: Alcohol dependence. National Health Services; 2020). Human data for acamprosate are lacking, so there is no recommendation for its use one way or another. In contrast, naltrexone is only minimally excreted into breast milk, and its use can therefore be continued. Gabapentin and topiramate do not have FDA approval for AUD but are commonly used off label for this indication. Gabapentin’s excretion into breast milk is minimal, and infant blood levels of topiramate are less than one-fifth of the maternal blood level. Although this implies that these drugs should be safe to prescribe, they have not been rigorously investigated in this context, so there are no firm guidelines regarding breastfeeding (Graves L et al, J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2020;42(9):1158–1173.e1). Evidence for the safety of bupropion and varenicline is similarly lacking. Nicotine replacements are safer alternatives to cigarette smoking. Psychotropic medications and breastfeeding Antipsychotics are found in low levels in breast milk, but the potential for extrapyramidal symptoms in infants is remote. Therefore, patients who need antipsychotics can take them and continue breastfeeding. Benzodiazepines can cause sedation and physiological dependence in infants, so although not completely contraindicated, low-dose and shorter-acting agents should be favored (Payne JL, Med Clin North Am 2019;103(4):629–650). For a summary of drugs and medications during breastfeeding, see the table at left. CATR Verdict: Patients who misuse substances on a regular basis should not breastfeed. In contrast, patients who have been on methadone or buprenorphine during pregnancy can continue these medications during lactation. For AUD, prescribe naltrexone but not disulfiram. Most psychotropics are safe during breastfeeding. Table: Impact of Drugs and Medication While Breastfeeding

Substances are transferred into breast milk by diffusion down a concentration gradient, with many variables determining how much ultimately makes it from high concentration (plasma) to low concentration (milk). The journey begins at ingestion, with the drug’s bioavailability determining how much of it is absorbed into the plasma. Once absorbed, drugs with high molecular weight, and those that are protein bound, will tend to stay in the plasma. Drugs that are lipid soluble or have a high pKa (more basic) will concentrate in the milk. In fact, drugs that are basic and lipid soluble can achieve an even higher concentration in the milk than in the plasma (D’Apolito K, Clin Obstet Gynecol 2013;56(1):202–211). We describe the properties of specific substances later in this article.

Renal and hepatic impairment may slow down drug elimination, causing drugs to accumulate in the body and, in turn, become more likely to be excreted into milk. Illicitly purchased drugs are often adulterated, and therefore mixtures of substances can find their way into breast milk, even if the patient has supposedly used only one drug.

Infants and young children, particularly those with certain underlying medical issues, are more vulnerable to the effects of drugs than their adult counterparts. Drug clearance gradually increases with age, from 5% in infants 24 weeks old to 100% by 68 weeks, or 1 year and 4 months of age (D’Apolito, 2013). Therefore, expect drug effects to be magnified in infants less than a year old.

The most commonly misused substance by patients who are breastfeeding in the US, by far, is alcohol: up to 50% in studies. Because alcohol has a low molecular weight, is not protein bound, and is basic, its level in breast milk parallels that in plasma. The alcohol level in milk peaks 30–60 minutes after maternal consumption, then falls rapidly. While the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends complete abstinence during breastfeeding, most experts say nursing is safe as long as less than 8 ounces of wine or 2 beers are consumed at a sitting and 2 hours have elapsed before breastfeeding or pumping (Reece-Stremtan S and Marinelli KA, Breastfeed Med 2015;10(3):135–141).

Other substances are a different story entirely. Heroin has low protein binding and high lipid solubility. As expected, it readily crosses into breast milk. Adulteration of heroin is quite common, with fentanyl, and analogues such as carfentanyl, being the most problematic. The risk of oversedation and overdose for infants breastfeeding from patients using heroin, and particularly heroin adulterated with fentanyl, is high. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) does not recommend breastfeeding for patients using heroin (Committee on Obstetric Practice and Breastfeeding Expert Work Group. Breastfeeding challenges. ACOG; 2021). One prescription medication to be especially wary of is codeine. Just like heroin, it is a prodrug that is rapidly metabolized into morphine. High levels of morphine can be found in the breast milk of patients taking codeine, and codeine can be found in many medications, such as analgesics and cough syrups.

Cocaine is particularly prone to accumulation in breast milk. In fact, the concentration of cocaine in breast milk is 8 times higher than in plasma. Cocaine has a bioavailability of 80%–90% as well as a high lipid solubility, which is why it accumulates in the breast milk so efficiently (Bartholomew ML and Lee MJ, Contemporary OB/GYN 2019;64(9):22–26). The CDC and the AAP therefore recommend total abstinence from cocaine while breastfeeding.

Like cocaine, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) also has levels in breast milk 8 times that of maternal plasma (Reece-Stremtan and Marinelli, 2015). As one of the primary psychoactive components of cannabis, patients who are breastfeeding should avoid using cannabis products. Studies have shown that the feces of infants contains THC metabolites, indicating that THC is not only consumed by infants through breast milk, but also absorbed and metabolized in their bodies. It is important to keep in mind that marijuana has become increasingly potent in recent years, potentially making the amount of THC in breast milk even higher than just several years ago.

Many patients are able to abstain from smoking, or at least cut back, during pregnancy. However, up to 50% resume their prior pattern of cigarette use postpartum (Reece-Stremtan and Marinelli, 2015). Nicotine and other agents in cigarettes are readily transferred to breast milk, and secondhand smoke exposure contributes to respiratory issues and sudden infant death syndrome. Therefore, we should encourage smoking cessation in all parents with newborns, whether they are breastfeeding or not.

While substance misuse should generally be avoided during breastfeeding, some medications that are commonly prescribed for addictive disorders are safe to prescribe while nursing. Both methadone and buprenorphine are lipid-soluble weak bases, but have a relatively high molecular weight and are protein bound. Therefore, these drugs only cross into breast milk in small amounts (D’Apolito, 2013). Breastfeeding is not only safe but encouraged in patients who take methadone and buprenorphine because the small amount of drug that finds its way into breast milk is safe and decreases the severity of neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (Committee on Obstetric Practice and Breastfeeding Expert Work Group, 2021).

The use of psychotropic medications is common in patients with addictions. Antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are safe during breastfeeding. Due to teratogenicity, carbamazepine and valproate are generally avoided during pregnancy. In contrast, these medications can be resumed or started during breastfeeding. Lithium is safe during breastfeeding, but pediatricians should check a blood level periodically or if the baby ever gets dehydrated, typically from a GI illness.