Opioid Treatment Options

The Carlat Addiction Treatment Report, Volume 6, Number 8, November 2018

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/catrv6n8/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Free Articles | Practice Tools and Tips | Psychopharmacology Tips | Substance Abuse

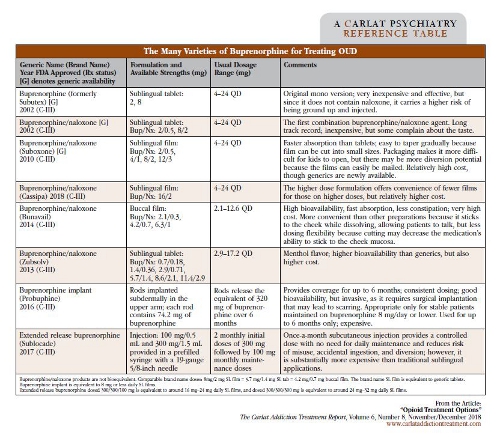

Opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment can be tricky, in part because it doesn’t respond well to detox and counseling-only approaches. The overwhelming majority of people relapse after such attempts, or even become more vulnerable to overdose because of decreased tolerance after detoxing. And the trajectory in this country is worsening—in 2016, we averaged around 115 opioid overdose deaths per day; in 2017, that number was estimated at around 134 per day (https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates). But we do have effective and underutilized medications to treat OUD: buprenorphine, methadone, and extended release injectable naltrexone. Let’s take a dive into these medication options. Buprenorphine The process of starting a patient on buprenorphine is called “induction,” because the first step is introducing it at the right time during opioid withdrawal. When performing an induction, make sure your patient has used no opioid in at least 12–24 hours (or 24–48 hours for the longer-acting methadone)—this should put the patient into mild to moderate withdrawal. We usually look for a score on the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS) of at least 8, though some guidelines suggest waiting until it reaches 12 (https://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/files/ClinicalOpiateWithdrawalScale.pdf). This waiting period is very important because giving buprenorphine too early can precipitate withdrawal. Pupil dilation may be the best way to assess for readiness to receive the first dose. Start with a small dose of buprenorphine, usually 2 mg–4 mg. Monitor the COWS after the buprenorphine dose, and if it’s still elevated after 2 hours, you can give another 2 mg or 4 mg. Continue this process until withdrawal subsides. Most patients find relief on 8 mg or less, but some may require 12 mg. Schedule regular office visits to monitor lingering withdrawal symptoms in the first days—nighttime body aches and sweats are common and can be addressed by dose adjustment. Clinicians can also do “home inductions”: Basically, if your patient isn’t in enough withdrawal in your office, you can prescribe the buprenorphine and instruct the patient how to start it at home when enough withdrawal is being experienced, and to contact you as needed. This is safe because although opioid withdrawal is uncomfortable, it is not usually medically dangerous. After induction and stabilization on an effective dose, you shift to the maintenance phase and can gradually reduce visit frequency, based on how well your patient does. Keep in mind that people with OUD who are at high risk for return to use but have not been recently using (eg, after release from incarceration), and are therefore not physically dependent on opioids, should be inducted and titrated more slowly and with lower doses. Buprenorphine is usually combined with naloxone. While naloxone is an opioid blocker, it isn’t active when taken sublingually or orally—only if it’s snorted or injected into the bloodstream. Therefore, it’s included in the buprenorphine preparations to reduce the potential for misuse. There are only a couple of practical reasons to use a buprenorphine-only product: if there is a documented allergy to naloxone, or if the patient is pregnant (to minimize exposing the developing fetus to medications, and to lower the potentially higher risk of withdrawal if the combination product is injected or snorted). There are several available formulations of buprenorphine (see table below). A long-acting buprenorphine subdermal implant called Probuphine became available in 2016. However, it’s only recommended for patients who have been stabilized on a sublingual film dose equivalent to 8/2 mg or less for 3 months. Buprenorphine implants require special provider training to prescribe and insert them into the arm, and they must be removed and replaced every 6 months. While this option may seem attractive because it avoids missed doses and lowers risk for diversion, clinical trials showed no difference in relapse rates compared to the traditional sublingual formulations (Rosenthal RN et al, Addiction 2013;108(12):2141–2149). Buprenorphine implants might be especially helpful for patients who travel abroad for extended periods, especially to places where access to continued buprenorphine treatment is limited. The newest buprenorphine preparation is potentially better, and comes as a monthly extended release subcutaneous injection branded as Sublocade. Patients have to be stabilized on a transmucosal dose of another buprenorphine product for only 7 days prior to administering the injectable. Recommended induction is 2 monthly injections at 300 mg, then a maintenance dose of 100 mg each month. Methadone Extended release naltrexone (XR-NTX) Naloxone CATR Verdict: Buprenorphine, methadone, and XR-NTX are effective medications and should be an integral part of treatment for most of our patients with OUD. Table: The Many Varieties of Buprenorphine for Treating OUD

While we used to tell our patients that both buprenorphine and methadone are first-line treatments, nowadays we increasingly think that buprenorphine should be the preferred agent, because it may be better at reducing mortality in the first month (Manhapra A et al, BMJ 2017;357:j1947). Buprenorphine has less associated stigma and poses fewer side effects (eg, QTc prolongation), drug interactions, and overdose risk than methadone. A special DEA waiver is required to prescribe it, but unlike methadone, buprenorphine can be prescribed through a regular office-based practice and doesn’t require a specialized clinic, making it more convenient for patients.

Whether first-line or not, good old methadone has a secure position in treating OUD. Consider methadone for patients who strongly prefer it, or who don’t do well on buprenorphine—for example, those with more severe OUD for whom even high doses of buprenorphine don’t provide enough coverage. Methadone should also be considered if observed dosing is warranted to enhance compliance and reduce the risk of diversion—though buprenorphine dosing can also be observed in a similar manner. Methadone can only be dispensed from federally regulated opioid treatment programs (OTPs). Methadone is dispensed daily to new patients, with take-home doses earned after a period of weeks to months depending on the clinic. OTPs are required to provide a package of services, including counseling. Methadone prolongs QTc, so be sure to check an electrocardiogram for patients with cardiac risk factors and limit other QTc-prolonging medications.

XR-NTX is administered through a monthly intramuscular injection. Oral naltrexone isn’t really a viable option—people stop taking it and relapse (Minozzi S et al, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011(2):CD001333). XR-NTX has had a slew of good data, including a 2017 study showing equal effectiveness to buprenorphine/naloxone over 12 weeks (Tanum L et al, JAMA Psychiatry 2017;74(12):1197–1205). But getting patients on it remains a challenge, and it still is considered second-line. Patients are typically required to stop using opioids for a full week or more before taking XR-NTX, providing plenty of time to relapse before even starting the medication. A recent Lancet study covered in the January/February 2018 CATR showed that 28% of XR-NTX patients dropped out of the induction period, compared to only a 6% dropout rate during buprenorphine induction (Lee JD et al, Lancet 2018;391(10118):309–318). But once patients were stable on XR-NTX, relapse rates were similar between the medications. Consider XR-NTX for highly motivated patients who prefer a non-opioid medication option. And be sure to counsel them that their risk of overdose greatly increases if they stop taking it, because of the high risk of relapse in addition to loss of opioid tolerance.

For any patient with OUD, prescribe intranasal or injectable naloxone for potential overdose reversal. Educate patients and their loved ones about overdose risk, prevention, and identification, and about how to use naloxone and respond to an overdose. More information for prescribers as well as patients and families is available by accessing the SAMHSA website at https://store.samhsa.gov/product/Opioid-Overdose-Prevention-Toolkit/SMA18-4742, or the Prescribe to Prevent website at http://prescribetoprevent.org. We also refer you to our coverage of naloxone in the March/April 2016 CATR.