Real-World Alcohol Use Disorder Treatment

The Carlat Addiction Treatment Report, Volume 10, Number 2&3, March 2022

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/catrv10n2-3/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Alcohol use disorder | Comorbidity | Dual diagnosis | Psychopharmacology | Psychotherapy

Ismene Petrakis, MD

Ismene Petrakis, MD

Addiction psychiatrist and professor at Yale School of Medicine. Chief of Mental Health, VA Connecticut Healthcare System, New Haven, CT.

Dr. Petrakis has disclosed that she participated in a study in which she did not receive any compensation from Alkermes apart from medication and Alkermes did not fund the study. Dr. Capurso has reviewed this material and found no evidence of bias pertaining to this educational activity.

CATR: Please tell us about yourself.

Dr. Petrakis: I’m an addiction psychiatrist, professor at Yale School of Medicine, and the Chief of Mental Health for the VA Connecticut Healthcare System. I have several research focuses, one of which is the treatment of individuals with comorbid psychiatric illness and alcohol use disorder (AUD).

CATR: We know AUD prevalence is higher among patients with mental illness. But how big of a problem is it really?

Dr. Petrakis: It’s a big problem. The prevalence of AUD in people who have mental illness is significantly higher than it is in the general population. And the risk goes both ways. By that I mean, if you start with a group of patients with psychiatric illness, the prevalence of AUD is higher than the general population, and if you start with a group of patients with AUD, the prevalence of psychiatric illness will be elevated. This holds for inpatient units and outpatient facilities alike, which suggests that AUD is important to look for in any mental health treatment setting, not just a specialty addiction clinic.

CATR: And how does the prevalence of AUD break down by diagnosis?

Dr. Petrakis: That’s a tough question to answer exactly because, believe it or not, there is no comprehensive single study that answers this question. So, that means comparing studies with differing methodologies. But it’s clear that there are increases across the board, with bipolar disorder probably conferring the greatest risk. For some context, the 12-month prevalence of AUD in the general population is less than 10% (Hasin DS and Grant BF, Soc Psych Psychiatr Epidemiol 2015;50(11):1609–1640). That number is in the range of 20% for schizophrenia; 30% for depression, ADHD, anxiety disorders, and PTSD; and up to 40% for bipolar disorder (Castillo-Carniglia A et al, Lancet Psychiatry 2019;6(12):1068–1080).

CATR: How do you suggest clinicians make a diagnosis? What should they be looking for specifically?

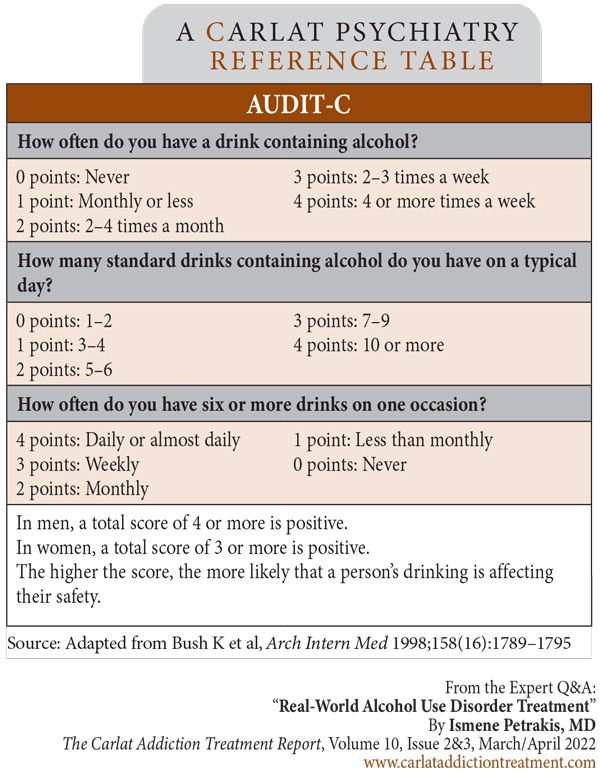

Dr. Petrakis: The first step is to make sure that there is a protocol for screening in place. Every patient having an intake in a mental health setting should be screened for AUD, and that screening should be repeated periodically, say every year or so. Here at the VA, we use the AUDIT-C, which is pretty easy to use (Editor’s note: See AUDIT-C questionnaire on page 4). Whatever screening tool you use, be sure you know what it’s meant for; the AUDIT-C won’t diagnose AUD, but it can identify who needs further investigation (Bush K et al, Arch Intern Med 1998;158(16):1789–1795; www.tinyurl.com/mba74m3f).

Table: AUDIT-C

CATR: By “needs further investigation,” are you referring to identifying patients with risky or hazardous drinking as opposed to necessarily meeting DSM-5 criteria for AUD?

Dr. Petrakis: Correct. The DSM-5 definition does not define quantity or frequency; what’s specifically important in making an AUD diagnosis is pattern of use. The DSM emphasizes use despite negative consequences, whether those consequences are social, psychological, or medical. People with AUD continue to drink despite their alcohol use causing problems. On the other hand, there are amounts of alcohol associated with medical problems, and consuming above this limit is what we call risky drinking, or hazardous drinking. Sometimes, patients consuming alcohol in the hazardous range aren’t facing any negative consequence yet and therefore don’t meet criteria for AUD, though they are certainly at a higher risk for AUD and medical issues down the line. These patients might be amenable to just some education. It can go a long way just telling them, “If you’re drinking above a certain amount, you are at risk of having alcohol-related problems.”

CATR: And what is that amount?

Dr. Petrakis: It’s different for men and women. For men, it’s greater than four standard drinks in a sitting or more than 14 drinks in a week. For women, it’s greater than three standard drinks in a sitting or more than seven drinks in a week. There are preliminary data that even small amounts of alcohol can be detrimental to health (Topiwala A et al, medRxiv 2021. Epub ahead of print), causing some to recommend that these guidelines be revised downwards, so these numbers may change.

CATR: That’s quite a difference between men and women.

Dr. Petrakis: Women’s higher total body fat percentage and slower ability to metabolize alcohol is part of the reason. But also, it is thought that there is a telescoping effect, or accelerated progression of disease, where women tend to get medical problems more quickly than men (Diehl A et al, Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2007;257(6):344–351). It’s not clear why that is.

CATR: And these are standard drinks you are referring to, correct?

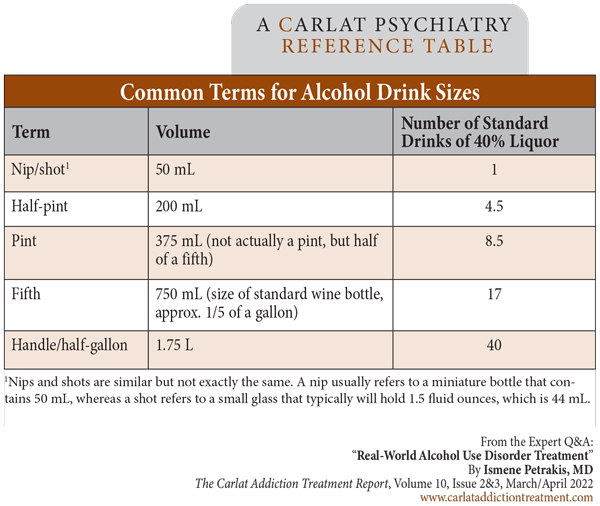

Dr. Petrakis: Yes. A standard drink is 14 grams of alcohol, which is a regular beer, a glass of wine, a mixed drink—they are all about equivalent. But many drinks have higher alcohol content than what is considered typical. High-alcohol beers and wines and high-proof liquors are common these days. And some containers hold more than you might think. Those red Solo cups are very bad—you can pour a lot in there! In order to really understand a patient’s drinking pattern, you have to ask what exactly the patient is drinking and convert it to standard drinks. It’s helpful to have a working knowledge of basic terms, too, like how many drinks are in a fifth, a nip, a half-pint, etc. (Editor’s note: See “Common Terms for Alcohol Drink Sizes” table on page 4.)

Table: Common Terms for Alcohol Drink Sizes

CATR: Let’s talk about medications for AUD. How generalizable are the findings of research trials for these medications to patients with mental illness?

Dr. Petrakis: That’s a good question. A lot of studies, especially the ones that led to FDA approval, excluded people who had comorbid psychiatric disorders. But there is growing interest in looking at these medications for patients with comorbidities, especially those that commonly co-occur with AUD, like depression, anxiety, and maybe PTSD.

CATR: Can you talk a little bit about specific medications?

Dr. Petrakis: Sure. There are three FDA-approved medications for AUD: disulfiram, naltrexone, and acamprosate. Disulfiram might be a special case, but naltrexone and acamprosate are certainly safe and effective in patients with comorbid psychiatric illness.

CATR: Why is disulfiram a special case?

Dr. Petrakis: Well, disulfiram can cause psychosis. It’s thought to occur because disulfiram inhibits dopamine beta-hydroxylase, an enzyme that breaks down dopamine and norepinephrine. Reports show that this is dose dependent, and psychosis tends to occur in people who’ve received high doses (Mohapatra S and Rath NR, Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci 2017;15(1):68–69). So, it’s generally safe to use at typical doses of 250–500 mg.

CATR: Can disulfiram be used for patients with preexisting psychotic disorders?

Dr. Petrakis: It’s not contraindicated, though I’d recommend using the lowest effective dose and monitoring carefully.

CATR: What about naltrexone and its effect on the endogenous opioid system?

Dr. Petrakis: As an opioid antagonist, people have wondered about naltrexone’s ability to precipitate or worsen depression and perhaps cause anhedonia. Mechanistically this possibility makes sense, but there’s no evidence that it occurs at all. If it does, it’s very uncommon. Of course, as an opioid blocker, naltrexone is contraindicated for patients taking opioid analgesics. But keep it in mind for people with comorbid opioid use disorder (OUD) because the intramuscular form is FDA approved to treat both.

CATR: And acamprosate?

Dr. Petrakis: It’s pretty benign and very well tolerated.

CATR: It doesn’t have great efficacy data.

Dr. Petrakis: That’s partially true. Some early data were promising, especially in trials out of Europe, and there have been studies here and there showing that it’s effective. But large trials in the US have been mixed. The largest one was the COMBINE trial, which was negative (Anton RF et al, JAMA 2006;295(17):2003–2017). Another trial around the same time showed a little bit of a signal, but again it wasn’t super encouraging (Mason BJ et al, J Psychiatric Res 2006;40(5):383–393).

CATR: Other non-FDA-approved medications are used for AUD as well. How do you approach choosing between them all?

Dr. Petrakis: For me, unless there is a contraindication, I think the first line is naltrexone. It’s FDA approved and has more evidence than anything else. It’s well tolerated and can help with cravings. The other FDA-approved medications, acamprosate and disulfiram, can be considered second line, though it’s very dependent on the clinical circumstances, especially when it comes to disulfiram. There are a lot of practitioners who shy away from disulfiram, and I understand that. I think it’s a good medication, but I wouldn’t use it in patients with very poor impulse control or significant medical illness that could put them at risk if they have a disulfiram-alcohol reaction. Adherence is also a big issue with disulfiram; as somebody taught me when I was a resident, it doesn’t help with sobriety if it’s sitting in a dresser drawer. It’s most useful if the patient is observed taking it.

CATR: And the non-FDA-approved medications?

Dr. Petrakis: I would go to those if naltrexone and acamprosate aren’t working, and maybe disulfiram if the patient is an appropriate candidate for that medication. There are a few medications that have been tested a lot but don’t have FDA approval. The first option in my mind is topiramate. There’s a lot of evidence for topiramate even though it’s not approved (Guglielmo R et al, CNS Drugs 2015;29(5):383–395). The problem with topiramate is its side effect profile; it can cause people to feel cognitive slowing.

CATR: And gabapentin?

Dr. Petrakis: I’d probably go to gabapentin after topiramate. Clinically it’s used all the time, and there’s some evidence for it, though that evidence is a bit mixed (Kranzler HR et al, Addiction 2019;114(9):1547–1555). While it can be helpful for some patients, I’m a little cautious about gabapentin since it can cause cognitive impairment. It might have some sedating effects that might help with anxiety, but that comes with the downside of being sedating. There are reports of gabapentin being used recreationally, though personally I don’t really see that much. A bigger concern is that gabapentin might amplify respiratory depression in patients who use opioids. In fact, it is associated with increased risk of opioid overdose (Gomes T et al, PLoS Med 2017;14(10):e1002396), so I would be very cautious in patients with comorbid AUD and OUD.

CATR: Any other medications?

Dr. Petrakis: Others have been studied, but nothing with strong support and nothing I would use routinely. (Editor’s note: See “Medications for Alcohol Use Disorder: An Overview” on page 1 for a review of medications for AUD.)

CATR: Can you say a little bit about combination pharmacotherapy?

Dr. Petrakis: The evidence is just not good. COMBINE was the largest trial looking at this, and it found naltrexone and acamprosate together were no better than naltrexone alone. We did a study where we combined naltrexone and disulfiram in people with comorbid psychiatric illness (Petrakis IL et al, Biol Psychiatry 2005;57(10):1128–1137). Our great hypothesis was that naltrexone would diminish craving and disulfiram would help control impulsive drinking, and that together they would be better than each one alone. But that’s not what we found at all; there was no advantage to the combination. There have been other trials, and a suggestion that combination therapy might be helpful at least early on (Anton RF et al, Am J Psychiatry 2011;168(7):709–717), but nothing has been really convincing that using multiple medications for the long-term treatment of AUD is the way to go. Does that mean you never try combinations? Maybe not. I would go with the evidence-based monotherapies before mixing them, though.

CATR: And what about psychotherapy for patients with comorbid AUD and mental illness?

Dr. Petrakis: There are really two questions there: psychotherapy for AUD itself, and psychotherapy for whatever the comorbid psychiatric illness might be. Let’s talk about psychotherapy for AUD first. There are several interventions designed to specifically address AUD, mostly derived from a cognitive behavioral framework (Magill M et al, Behav Res Ther 2020;131:103648). I think these are important and can be very helpful for some patients.

CATR: And what about psychotherapy for the comorbid mental illness?

Dr. Petrakis: Psychotherapy certainly isn’t contraindicated. At one time, there was concern about patients with comorbid PTSD undergoing exposure therapy or cognitive processing therapy. There was worry that the anxiety brought up in the treatment might drive patients to drink. But I don’t know of any data that bear this out. In fact, there’s evidence that exposure therapy might be the optimal approach for patients with comorbid PTSD and AUD (Norman SB et al, JAMA Psychiatry 2019;76(8):791–799).

CATR: Many practitioners have differing beliefs about the proper chronology of treatment. Should treatment focus on AUD first and then comorbid mental illness, the other way around, or both at once?

Dr. Petrakis: Well, it depends how the patient is presenting; it’s a question of acuity. Clearly, for someone presenting with suicidality, safety and stabilization are the priority. Similarly, if someone is presenting in withdrawal, detox is the most pressing issue. But those are obvious examples. In general, you shouldn’t wait to treat either the AUD or the other psychiatric issue. The old-fashioned approach said patients should be sober for a month before treating depression because mood gets better over time. And while it’s true that mood does tend to get better over time, that approach results in a patient waiting around suffering from depression, risking dropping out of treatment, and possibly having a bad outcome.

CATR: And most of the pharmacologic approaches are quite safe even if a patient is drinking.

Dr. Petrakis: Nowadays, yes. Prescribers worried about giving medications like tricyclics, MAOIs, or lithium to heavy drinkers. But SSRIs are safe and shown to be effective in combination with naltrexone for depression (Pettinati HM et al, Am J Psychiatry 2010;167(6):668–675). At this point, concurrent treatment really is standard of care.

CATR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Petrakis.