Assessing and Treating Bulimia in Teens and Young Adults

The Carlat Child Psychiatry Report, Volume 13, Number 5&6, July 2022

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/ccpr13n5-6/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Assessment | Bulimia Nervosa

James Lock, MD

James Lock, MD

Professor of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Pediatrics, Stanford University. Senior Associate Chair for the Department of Psychiatry and Director of the Eating Disorders Program at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, Palo Alto, CA.

Dr. Lock has disclosed that he is the co-owner of the Training Institute for Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders. Dr. Feder has reviewed this educational activity and has determined that there is no commercial bias as a result of this financial relationship.

CCPR: When does bulimia typically present?

Dr. Lock: Symptoms usually begin at about 15 or 16, but patients may not meet full diagnostic criteria for bulimia until 18, 19, or 20. Often they are off at college by then, so they’re being identified and treated more at that stage.

CCPR: What is the difference between “bulimic symptoms” and DSM-5 “bulimia nervosa”?

Dr. Lock: Someone who binge eats and purges but does not do so as frequently or as persistently as required by the DSM-5 would be described as having bulimic symptoms. The DSM-5 criteria require weekly binge eating and compensatory behaviors (eg, purging) for three months as well as overvaluation of shape and weight in terms of self-worth.

CCPR: How many teens have bulimia or bulimic symptoms?

Dr. Lock: About 1% of teens or fewer meet diagnostic criteria. An additional 3%–5% of adolescents have disordered eating, including bingeing and purging, that don’t reach diagnostic thresholds. By age 20, about 2%–3% of young women will have bulimia (Hoek HW, Curr Opin Psychiatry 2016;29(6):336–339).

CCPR: Is there a way to predict which teens who engage in these behaviors will cross the threshold to bulimia?

Dr. Lock: We don’t know what risk factors predict persistent bingeing, but early intervention is likely to change trajectories. If you are treating a kid for depression and they say they’re bingeing and purging, look for treatments to assist them with managing these behaviors. Don’t let kids who are bingeing and purging just continue without intervention. These are high-risk behaviors that alter their life experience.

CCPR: How do we make it clear to teens and parents that bulimia is something they need to take seriously?

Dr. Lock: Talk about medical problems. Our bodies are not designed to tolerate the change of volume associated with bingeing and purging, and the changes in potassium are hazardous to our cardiac and muscle systems. You get orthostatic hypotension with fainting because of dehydration from vomiting. Binge eating and purging also damage the gastrointestinal system. Teens do drastic things out of dissatisfaction with their weight and shape and erode their self-esteem, their confidence, and their relationships.

CCPR: How do these emotional impacts affect the person over time?

Dr. Lock: These behaviors generalize, becoming coping strategies for other emotional problems—when the person has an argument, instead of addressing it, they eat and throw up. They use a dangerous behavior that was originally related to worries about appearance to cope with other problems in their life.

CCPR: Does the person experience temporary relief through bingeing?

Dr. Lock: Yes. It’s like cutting. There’s a dissociative quality to binge eating. People flood themselves with food to block feelings. The same is true with purging. These behaviors can temporarily block the pain of depression or anxiety. They are intermittently self-reinforcing and therefore hard to change.

CCPR: How does this cycle get started?

Dr. Lock: A teen who feels like they aren’t attractive might try dieting. They get hungry, then they eat, then say, “I’ve failed my diet.” They try it again with more intensity, but their hunger cues become stronger. This leads to uncontrolled binge eating.

CCPR: How is bulimia different from anorexia?

Dr. Lock: The person with bulimia feels like a failure at dieting, exercise, and the rest of life. It’s a constant erosion of self-worth. Every time they binge and purge, they feel bad about it. But they feel stuck with it. They’re ashamed and don’t want their parents or anyone else to know. They’ll binge and purge in the middle of the night or find other ways to hide what they’re doing. By contrast, the person with anorexia nervosa has a sense of accomplishment from doing the work and losing weight.

CCPR: Do teens admit to bingeing and purging if you ask them?

Dr. Lock: There are structured assessments, but usually it gets identified because a parent will notice vomit in or on the toilet. Family members may hear them vomiting or notice cereal boxes gone from the pantry. Teens seldom report their bulimia because they’re ashamed. Sometimes girls will binge and purge together in a network, usually in college or girls’ schools. Screens such as the Sick, Control, One, Fat, Food (SCOFF) and Eating Disorder Screen for Primary Care (ESP) that the teen fills out sometimes yield information (Cotton MA et al, J Gen Intern Med 2003;18(1):53–56). But your best source is a parent or a sibling who says, “She’s throwing up every day in the bathroom.”

CCPR: How do parents react to these behaviors?

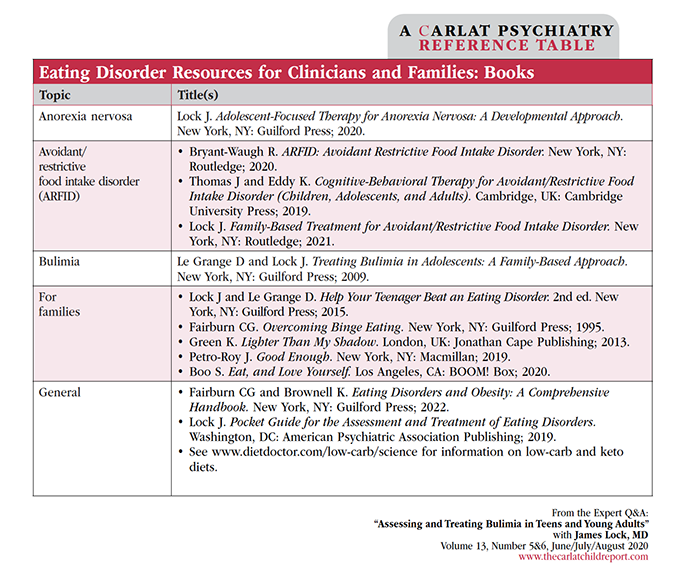

Dr. Lock: Parents are often aggravated. With bulimia, their child is throwing up, wasting food, making a mess. Parents can be critical and lack empathy because they dislike or are disgusted with the behavior. (Editor’s note: For a good resource for parents, see Dr. Lock’s book Help Your Teenager Beat an Eating Disorder, listed in the “Eating Disorder Resources for Clinicians and Families: Books” table at the end of this Q&A.)

CCPR: How do you foster a trusting relationship with the teen to talk about these symptoms?

Dr. Lock: Use a matter-of-fact approach. Say things like: “A lot of teenagers have these kinds of issues. I’m going to ask you about how you’re feeling about your appearance and your weight. Have you tried to do anything about it, like diet or other things?” If they answer yes, ask: “Have you ever tried making yourself throw up?” Don’t let your own shame or anxiety interfere. When you are comfortable asking these questions, your patient will be more able to tell you what they are doing.

CCPR: Is bulimia different in boys vs girls?

Dr. Lock: You might have more boys using exercise as a purging strategy or using drugs that affect body shape and weight. Some sports increase risk for bulimia, especially ones with weight standards. If you have a wrestler or gymnast in your office, screen that person for bulimia. (Editor’s note: See CCPR July/Aug/Sept 2021 for more on performance-enhancing drugs.)

CCPR: Are there differences in bulimia among various cultural, racial, or ethnic groups?

Dr. Lock: Eating disorders are thought of as primarily affecting girls or young women who are White and upper middle class, but eating disorders occur in all populations, all socioeconomic groups. Some data suggest that binge eating and bulimia are more common than anorexia in Black communities, but there’s too much noise in the data to draw conclusions (Hoek, 2016; Hoek HW et al, Am J Psychiatry 2005;162(4):748–752).

CCPR: How can we more competently assess for eating disorders?

Dr. Lock: Get comfortable asking the questions. By age 20, about 8% of kids have an eating disorder (Hoek, 2016). That rivals most other psychiatric diagnoses in children and adolescents. We must increase our exposure to training programs and professional meetings covering developmental aspects, assessment, screening, and treatment for eating disorders. It’s also good to have an up-to-date handbook on eating disorders in your office library.

CCPR: How do you decide whether to treat someone yourself or refer out?

Dr. Lock: The treatment of choice is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). If you know how to do CBT and learn CBT for bulimia, then you can treat it. It’s an outpatient treatment unless there’s extreme behavioral difficulty with unrelenting bingeing and purging. We did a study of kids ages 12–18 with binge eating, purging, and bulimia where we compared CBT to family-based treatment, and we found that family-based interventions were more effective with this younger cohort (Le Grange D et al, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2015;54(11):886–894.e2).

CCPR: Why do you think family-based treatment works better than CBT in younger kids?

Dr. Lock: Adolescents benefit from having help from their parents. Parents can also modify environmental cues and opportunities. For instance, they can stop purchasing the food that their teen tends to binge on, and even get rid of scales in the home. Also, family-based treatment can move parental criticism and judgment to acceptance, which really changes the psychological milieu of the adolescent.

CCPR: Can medications help bulimia in teens?

Dr. Lock: Serotonin reuptake inhibitors in relatively high doses have been studied in adults. Medication is better as an adjunctive treatment for adults, not as a standalone. We have had hardly any studies in children and adolescents, but we might try it as an adjunct to CBT. (Editor’s note: Remember that there is an FDA warning about seizure risk for bupropion with bulimic emesis.)

CCPR: What about specific treatment programs for teens with bulimia?

Dr. Lock: Think carefully before referring to a program. Many therapists in the community treat kids for bulimia, but programs have a different dynamic. You have to decide whether putting a patient in a program might exacerbate or create a community of illness. If a teen has mild symptoms and is placed in a group with complex patients, they might adopt chronic and severe patterns of thinking and behavior. Effective behavioral change must take place in the environment where it will generalize—at home with the family and in school, not in contained environments. It doesn’t mean programs don’t have a role, but to maintain behavioral change, to generalize it and hold it, the treatment must be done in generalizable environments, which means home, school, family. (Editor’s note: For outpatient care of bulimia, we suggest a team that includes a primary care provider to monitor electrolytes and decide when a patient needs a medical hospitalization.)

CCPR: What is the prognosis for bulimia?

Dr. Lock: For bulimia, mortality rates vary widely but are probably not as high as for anorexia. You can get cardiac arrest with changes in potassium, but also chronic morbidities such as metabolic and GI problems. The morbidity and psychological costs are extremely high. In our studies, about 60% of teens with bulimia or sub-threshold bulimia met diagnostic criteria for major depression. With treatment, about 40%–50% recover from bulimia. The treatments that are most effective for adolescents are family-based treatment and CBT.

CCPR: What about other comorbidities, like emerging character disorders and trauma, sexual abuse in particular?

Dr. Lock: Sexual abuse and trauma are risk factors for eating disorders, but they’re not specific for eating disorders. People who have insecure relationships often feel vulnerable, developing unstable interpersonal relationships and anxiety symptoms, and those patients are at higher risk for bingeing and purging than teens who are just focused on weight and shape. This might include 25% or 30% of teens with bulimic symptoms. That’s a clinical observation. I wish we had better data.

CCPR: Any concluding thoughts?

Dr. Lock: If you’re a child psychiatrist, expect to see eating disorders in two or three out of every 10 patients (Hoek, 2016). Screen for eating disorders and get information from parents and other family members. Pay attention to environments that are risky, including sports or school situations. And know that there are effective interventions that can help. There are good resources at the websites for the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (www.aacap.org) and the National Eating Disorders Association (www.nationaleatingdisorders.

CCPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Lock.

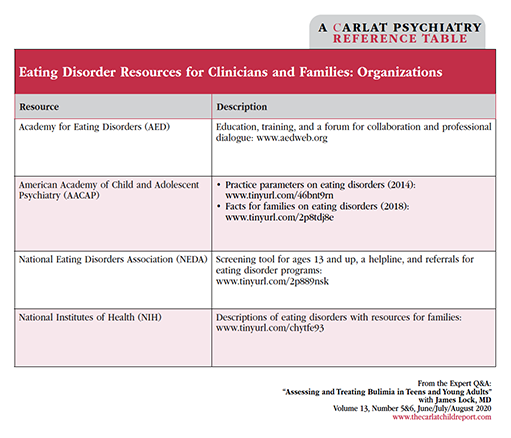

Eating Disorder Resources for Clinicians and Families: Organizations

(Click to view full-sized PDF.)

Eating Disorder Resources for Clinicians and Families: Books

(Click to view full-sized PDF.)