Differentiating ADHD From Anxiety: Tips for Clinicians

The Carlat Child Psychiatry Report, Volume 9, Number 2&3, March 2018

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/ccprv9n23/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: ADHD | Anxiety | Child Psychiatry | Practice Tools and Tips

Paula Jurczak, BSW

Child and family therapist.

Joshua Feder, MD

Editor-in-chief, The Carlat Child Psychiatry Report.

Ms. Jurczak and Dr. Feder have disclosed that they have no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

When parents bring in their kids for concentration, attention, and learning issues, it’s common to assume a provisional diagnosis of ADHD. In many children, however, anxiety can be the real cause of these problems.

Studies have long shown that about two-thirds of children and adolescents who present for ADHD evaluation have comorbid conditions, including learning disorders, mood disorders, anxiety disorders, sleep problems, and disruptive behavior disorders (Biederman J et al, J Affect Disord 1998;51(2):101–112). These underlying problems can all drive anxiety, and we must address each one to optimize treatment.

In this article, we will talk about how anxiety can profoundly affect cognitive ability in children, and give you tips on how to identify and treat this problem. But let’s start by looking at the mechanisms of anxiety and how anxiety interferes with cognitive processes.

Mechanisms of anxiety in children

Most of us have experienced the muddled thoughts anxiety can cause. Public speaking is a classic and common example: You are an expert on a topic and normally an articulate person—but on the podium, panic suddenly strikes, and you forget your carefully practiced train of thought.

Bruce Perry, MD, PhD, whose career has focused on how stress and trauma affect child development, explains how the arousal states of anxiety interfere with the thinking of children and adolescents. According to Perry, there are five levels or states of general arousal: calm, alert, alarm, fear, and terror (See “Clinical Applications of the Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics,” at http://bit.ly/2BMtGHI).

In the calm state, we can think and reflect, alone or with others. Our highest, most fully developed cognitive abilities are intact and active.

The alert state is the workhorse of everyday life; it provides us with the level of arousal necessary to ensure that we pay attention to the world around us. As an example, children are in the alert state when they raise their hand in class, the teacher calls on them, and they easily recall studied information.

In the alarm state, our ability to use learned skills and cognitive abilities is impeded, and ideas and judgments are cast in emotional terms. Children with anxiety-related concentration problems spend much of their time in this state. This is also the state where we might see tantrums, avoidance of tasks, comfort eating, or—in teens—substance cravings.

In the fear state, children tend to run off and escape from a classroom, from a house, or from your office. Alternatively, children might hide under the bedcovers at home or in the school nurse’s office, or even cover their heads and faces with their sweatshirts during your appointments.

Finally, in the terror state, arousal is so high that it either renders children unable to respond or causes them to wildly strike out. While these episodes may pass, they can be of such severity that they often result in a referral for mental health evaluation or even an assessment for inpatient care.

How to identify anxiety as the cause of inattention

Knowing that anxiety may impair cognition is the easy part. What’s tougher is distinguishing anxiety—as opposed to ADHD—as the cause of poor attention.

In your assessment, try to talk with the child, parents, teachers, and other caregivers. Ask them about the difficulties they observe, including which kinds of academic and social activities go well for the child, and which ones don’t.

For the activities that go well, get a sense of whether the child is in a calm or an alert state, and how the child is thinking, relating, and concentrating during those times.

For the activities that are not going well, ask about how the child is different when in an alarm state. Often, as children enter this state, their thinking becomes black and white, more concrete, and less abstract. They lose the ability to see the big picture. As an example, children might not understand that if they pay attention now in math class, afterward there will still be time to play.

Ask about changes in the child’s scope of time. When anxious, children will have less ability to think about yesterday, today, and tomorrow, and are more fixated on the frustration of the moment.

Find out what the child wants from the people who can help. Children in a calm or alert state are more able to ask for and accept help from adults. In an alarm state, they might want to take a break or have a snack. In a fear (or terror) state, they are not able to ask for help.

After the fact, children often have trouble recalling what an episode was like—this is an indication that arousal was overwhelming, that at the very least it was an alarm state, and that it interfered with creating sustained memories.

Helping children lower anxiety

There are some useful tips that can help you specifically treat the type of anxiety that leads to inattention. Consider the following:

Planning ahead: Catalog. By asking the right questions, you can make a list of the specific arousal states the child is experiencing during different activities. In particular, identify activities that are difficult for the child, and if the overall level of arousal is too high during a particular activity. Share this catalog with parents and teachers so that they can recognize when the child is over-aroused and anxious, and can find new ways to help the child based on this understanding.

During tough moments: Assess-Help-Recover. When a child is over-aroused, it is common for adults to become upset themselves and respond in a rigid, commanding, or angry manner. This generally creates more anxiety in the child, resulting in worsening of symptoms. Whether in your office, at home, or in school, you or the caregiving adult can try this simple plan, developed by Dr. Diane Cullinane, to help things go better:

- Assess: Identify the state that the child is in.

- Help: See if the child can tell you what might help, and try to offer some of what the child wants. If the child cannot tell you, try staying calm and present, using fewer words, or giving the child some space while ensuring safety.

- Recover: Allow the child time to recover.

Replace questions with statements. In trying to help an anxious child talk through difficulties, avoid the question form of inquiry. Questions create a new demand of the child and can increase anxiety. Statements are usually less anxiety-provoking and allow the child an opportunity to correct you. For example, instead of saying, “Why are you so angry?” you might say, “I can see that you are really angry. Help me understand why.” The child might tell you why, or correct you and say, “I’m not angry, I’m scared because …”

Use “we” language. Using phrases such as “we can figure this out” is different from telling the child, “You need to …” or “I’m going to …,” which often raises anxiety levels. Stating that you (rather than we) are solving the problem can keep the child from building a sense of competence.

Adjust your adult intensity. In most instances, it’s important to stay calm and empathic, and not use a lot of words. This approach may allow the child to calm down. If it doesn’t work, it is often because the child feels you don’t care enough. Consider turning up your empathic intensity so you come off as concerned without being upset. For example, say to the child, “That sounds awful.” The child might then feel better understood and can step down a notch from high arousal to a more workable level of concern.

Take a deep dive. Once the difficult moment has passed, the team needs to sort through and address the various reasons for the child’s sensitivity to a situation. Although ADHD might be a factor, the entire differential should be considered. Look at sensory, motor, and specific learning challenges; biological rhythms, such as sleeping; toileting and eating; and other psychological, psychiatric, and social factors.

Choose the right therapy. There are many types of therapies designed to help children with anxiety. These include cognitive behavioral approaches, psychodynamic psychotherapies, play therapies, and supportive office care. Most therapies require a calm, clear, and patient approach. Harsh limits or edicts typically result in worsening symptoms, or if the child doesn’t comply, a poor ability to generalize and adapt to new challenges.

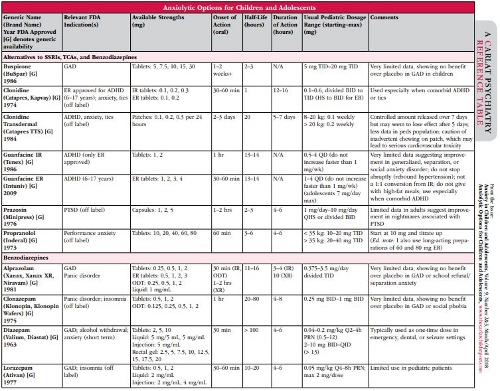

Choose the right medication. Many medications can be helpful for anxiety. (See the medication table below.) While medication alone is not likely to address the child’s problems, it can often make therapy and daily management more successful. Think about arousal levels and consider use of central alpha agonists, such as guanfacine, before resorting to SSRIs, which may have more side effects. As benzodiazepines may create even more unintended problems, we recommend avoiding them. (See lead article “Benzodiazepines in Children and Adolescents.”) Other medications to consider include beta blockers, such as propranolol, and—when used with care—occasionally the older tricyclic antidepressants. The most severe forms of anxiety sometimes require consideration of anticonvulsant-class medications or antipsychotics; however, look again at the overall plan of therapy and support to the child before getting into complex psychopharmacology.

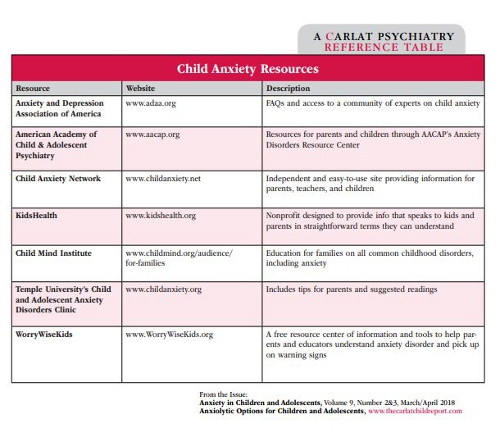

For more information on resources for child anxiety, see the table above. It can be used as a handout for parents and children as well as educators.

CCPR Verdict: Consider anxiety as a central factor when a child has poor academic function or poor attention. You should do a thorough assessment and model good, responsive caregiving practices in your office, including parents and/or teachers in the assessment and treatment plans. With these steps, the child will often do much better.