Practical Issues with Prescribing ADHD Meds

The Carlat Child Psychiatry Report, Volume 13, Number 3&4, April 2022

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/ccprv13n3-4/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Adhansia | ADHD | Aptensio | Contempla | Dyanaval | Evekeo | Jornay PM | Mydayis | Qelbree | Quillivant | Stimulant treatment | Zenzedi and ProCentra

Anne Buchanan, DO

Anne Buchanan, DO

Child & Adolescent Psychiatrist with New York City Health and Hospitals, Bellevue, and Maimonides Medical Center in New York, NY.

Dr. Buchanan has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

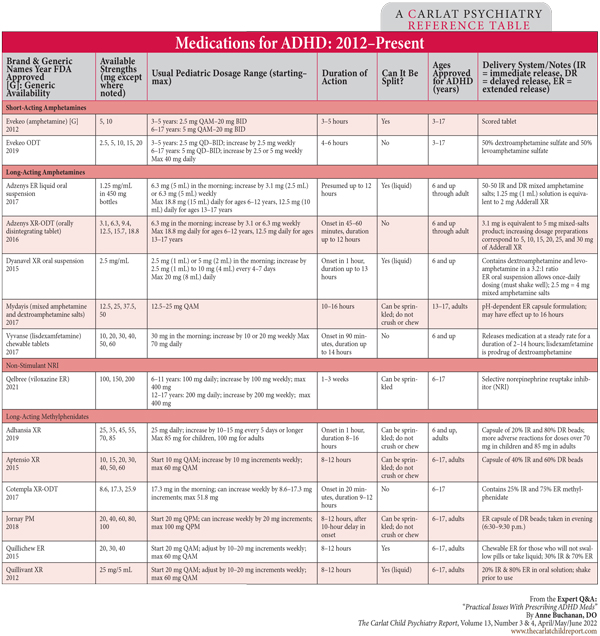

We spoke with Dr. Buchanan about choosing medications for ADHD in 2017, and she is back now with an update. In addition to this interview, check out the table below for an overview of ADHD medications over the past decade.

CCPR: Thanks for talking with us, Dr. Buchanan. Please help us make sense of the many new ADHD medications.

Dr. Buchanan: Sure. In the amphetamine group, there are four new long-acting options: 1) Mydayis; 2) a chewable Vyvanse; 3) a new liquid formulation, Dyanavel; and lastly 4) Adzenys, which comes in both a liquid and an orally disintegrating tablet. In the long-acting methylphenidate category, there are six new options—Adhansia, Aptensio, Cotempla, Quillivant (which has both liquid and chewable options), and Jornay PM (which is both delayed release and long-acting).

CCPR: Wow. And what new short-acting amphetamines do we have?

Dr. Buchanan: The new short-acting amphetamines are Evekeo, which has both a regular tablet and an orally disintegrating option; Zenzedi; and ProCentra, a liquid. Probably the most interesting new medication is Qelbree (viloxazine), which is a non-stimulant selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, just approved a few months ago. But in my personal prescribing habits, I tend to be a bit skeptical and a late adopter of new medication.

CCPR: How did you come to be a late adopter?

Dr. Buchanan: The majority of my clinical work is in the emergency room setting. Working in the emergency room, I evaluate children who are coming from every level of care—from private practices to foster care agencies to residential and juvenile justice facilities. I have the luxury of a bird’s-eye view of what my colleagues in the community are prescribing and how children are doing. I tend to wait in my own prescribing until I have a sense of how kids are doing on the newer medicines. Unfortunately, if they’re in the emergency room, there’s a chance they’re not doing so well!

CCPR: So, how do we fit these new medicines into clinical decision-making?

Dr. Buchanan: These new meds are still methylphenidate- or amphetamine-based products, except for Qelbree. I see them as an opportunity to fine-tune symptom coverage and ease of administration, especially for those who struggle to swallow pills, such as small children, or for kids with intellectual or developmental disabilities. We now have more chewable, orally disintegrating, and liquid products in our arsenal. On busy school mornings, it’s much easier for parents to give these than to snip capsules and pour beads.

CCPR: Are there other advantages to these new medications?

Dr. Buchanan: Some of them are marketed as lasting much longer, such as 16 hours. This could mean not having to deal with booster doses for children who need additional coverage in the late afternoons or early evenings. I think it’s great that there are so many options to fine-tune regimens and make things easier for kids and families. However, keep in mind that these new medications will not revolutionize our ability to treat the core symptoms of ADHD. There aren’t new mechanisms of action in terms of their pharmacology.

CCPR: We are all aware that there is so much marketing for new medications, and families often ask us for the newest products. How do you talk with parents who come to you with questions like this?

Dr. Buchanan: Most parents are able to understand the explanation that the active ingredients in the older and newer stimulants are the same. I talk about how some of our medicines have been around for decades. We know they work and they’re more affordable for you, for your insurance plan, and the healthcare system in general. I tell them that there’s usually no reason to start with the newer medications, but that we’ll try different ones until we find the medicine that’s the right fit.

CCPR: How soon after prescribing do you suggest we check in with patients and families?

Dr. Buchanan: Ideally, I would have a child come back in one to two weeks after initiating any new medicine, but that’s often hard to do in community clinics or busy practices. I think as a field we’re pretty good at getting kids back in a month, but some of our primary care colleagues don’t have that mindset or availability. I have seen clinical documentation from non-psychiatrists that give directions for titration, with follow-up in three months. Child psychiatrists might recommend going from a half tab to a full tab and see them back in a week, but generally they wouldn’t set up a detailed titration plan with a follow-up so far out. I think for primary care colleagues or other non-psychiatrists, seeing patients back as quickly or often as we do is more challenging. Then the question is, is that the right practice setting for that child? But it may be the only option.

CCPR: You work with families with a range of socioeconomic circumstances. Does that affect prescribing, and if so, can you speak to these differences?

Dr. Buchanan: I think polypharmacy can be a problem in children of lower socioeconomic status. I think at least one reason is lack of access to fellowship-trained child and adolescent psychiatrists, as well as lack of access to quality, evidence-based psychotherapy. Due to high demand, community clinics are often put in the position of utilizing different types of clinicians with different education, training, and experience, sometimes including unlicensed clinicians. A child might benefit from CBT, parent-child interaction therapy, or family therapy with a trained, licensed, and experienced clinician; 30-minute sessions every other week are rarely enough. Many families don’t have the time or resources to attend frequent appointments for therapy, and intensive outpatient programs or home-based programs may not be available or may have long waitlists. Clinicians are desperate to help these children and families, and medications may be the only available tool. It’s just not possible to do all the things we know that these families would benefit from. It’s an insurmountable problem.

CCPR: How good are clinicians at appreciating the clinical complexity of these cases?

Dr. Buchanan: Many of our non-psychiatric colleagues see ADHD as straightforward, and they’re comfortable with stimulants. But teasing out ADHD can be complex and incredibly nuanced in many cases. ADHD symptoms are nonspecific, and comorbidities are the rule rather than the exception. Anxiety and atypical depression can look like ADHD, as can autism spectrum disorder, developmental delays, and learning disorders. Trauma, especially complex trauma and its related attachment disruptions, are probably the biggest confounders. Often I review clinical documentation or speak to a clinician only to discover that trauma has not been adequately assessed for. Pediatricians and child neurologists are wonderful at treating ADHD when the diagnosis is straightforward, but I wouldn’t expect them to have the training to evaluate for the effects of complex childhood trauma, attachment, and anxiety.

CCPR: With so many kids seeing non-psychiatrists, at least in the first rounds of treatment, how we can better support these colleagues?

Dr. Buchanan: Develop professional relationships with pediatricians, neurologists, or other clinicians in your community who treat children. This helps them know where to turn when a patient starts to feel outside their scope. When a child is failing first-line treatments, that may signal that the child needs an evaluation with an expert. Where child and adolescent psychiatrists are scarce, develop a system through which the child psychiatrist can refer back to the original referring clinician for management, with open communication, once the patient has been stabilized. This frees child psychiatrists to evaluate more patients and allows non-psychiatrists to treat with confidence. New York state offers Project TEACH, a free same-day consultation with a child psychiatrist line for primary care physicians and other clinicians (www.projectteachny.org).

CCPR: When we do encounter a child with straightforward ADHD, how do we help parents decide how to proceed with medication treatment?

Dr. Buchanan: I generally see three types of parents. There are parents who say, “I need help; tell me what to give my kid and I’ll fill it today.” There are parents who are adamant that their child not take medications, usually because they’ve heard reports that “these medications make kids into zombies.” Finally, there are parents in the middle who want to help their child but are understandably anxious about the idea of their child taking medication.

CCPR: How do you manage these different types of parents?

Dr. Buchanan: For the parents that are on board, we start with the basics and go from there. For parents who have heard negative things about medications, I remind them that we have no idea what happened with that kid down the street who may or may not look like a zombie. We don’t know that child’s diagnosis, what symptom is being targeted, or why a particular medication is being tried. I tell them that we’re going to focus on what’s going on with their child and present the evidence-based options that we have. I note that I use these medications all the time and I have a lot of comfort with them. I simply ask that they keep an open mind and work with me, and I stress that I would never ask them to stay with something that their child doesn’t feel good on. I also tell them that I will continue to work with them to find whatever combination of medications and therapy is helpful.

CCPR: What if reassurance doesn’t work?

Dr. Buchanan: I don’t want parents to feel pressured. I want them to want to try medications because they see that their child is suffering, and they want to help their child succeed. But external forces will often do the job for me, whether it’s a parent-teacher meeting or frequent calls to come pick up their kid or the after-school program saying, “I’m sorry, your kid can’t come any more.” (Editor’s note: For strategies to address parents’ specific concerns, see “Talking With Parents About Stimulant Treatment” in this issue.)

CCPR: If they are willing, what’s the next step?

Dr. Buchanan: I try to be flexible even if I think a stimulant is the right choice. We can start with therapy, with medication, or with both. If the parent wants to start with something else, I’m happy to do that. If a parent asks what I recommend, I will say what I would start with, but I let them choose. If the child is a little older, I’ll let the child weigh in on what they would like to try.

CCPR: How do you get buy-in?

Dr. Buchanan: While academic performance is usually part of the issue, I will focus wherever the parent and child are experiencing the most frustration. For some parents, the child’s behavior is more of an issue than their grades. For other families, the child’s bedtime routine and poor sleep habits are causing havoc, so maybe instead of a stimulant we start with guanfacine or clonidine at night. If we have success, then I have some parental buy-in to try a stimulant if I think it is still needed.

CCPR: Speaking of other medications, where do you see the role of atomoxetine and viloxazine in comparison to stimulant treatment?

Dr. Buchanan: I consider atomoxetine third line, after stimulants and alpha-agonists, but there are always children who don’t tolerate stimulants, and alpha-agonists may not provide the necessary symptom relief or may be too sedating. For these children, atomoxetine can be a good alternative. In an emergency room situation we need prompt symptom control; however, atomoxetine needs titration and time to work. Viloxazine may be similar. Remember that viloxazine is a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and ideally would not be prescribed to a child who is already on an SSRI for depression or anxiety, as many kids with ADHD are. I have seen one child taking escitalopram and viloxazine in the emergency room with symptoms of activation from both serotonergic agents.

CCPR: Getting back to parents, how do you work with parents who are interested but hesitant to go forward with medication for ADHD?

Dr. Buchanan: I make sure they’ve been given all the necessary information. Then I tell them, “I understand that you’re feeling a little bit ambivalent and aren’t sure where to start. Let’s try working on sleep and more structure at home. Continue with the therapy for a bit and then we’ll have you come back and see how things are going.” People respond when they make the decision themselves rather than feeling pushed. Sometimes I say, “I’ll just submit the prescription. You don’t have to take it. But if you decide as a family that you want to try it, it will be there.” This is about giving our patients agency and self-determination. You want people to feel empowered to make their own choice. You’re going to be more successful if they’re choosing what to start, when to start, where to start—giving parents that level of autonomy feels better for everybody.

CCPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Buchanan.

![]() To learn more about this and other clinical topics, subscribe to our podcast feed. Search for “Carlat” on your podcast store

To learn more about this and other clinical topics, subscribe to our podcast feed. Search for “Carlat” on your podcast store