Tools to Help Kids and Teens to Sleep Better

The Carlat Child Psychiatry Report, Volume 12, Number 7&8, October 2021

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/ccprv12n78/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Assessment | CBTi | circadian system | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia | Sleep | treatment

Rafael Pelayo, MD, FAASM

Clinical professor and Associate Division Chief for Community Commitment and Engagement for the Sleep Medicine Division, Stanford University School of Medicine. President, California Sleep Society. Author of How to Sleep: The New Science-Based Solutions for Sleeping Through the Night (Artisan, 2020).

Dr. Pelayo has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Sasha is a 13-year-old whose grades are slipping. She reports trouble concentrating in school, and her parents are worried she might have ADHD. On taking a history, you learn that Sasha stays up late and gets up early, obtaining about six hours of sleep per night.

Adolescents have been reporting less sleep over the past 20 years in what’s been termed “The Great Sleep Recession” (Keyes KM et al, Pediatrics 2015;135(3):460–468). Although recommended sleep is 9–12 hours for children ages 6–12 and 8–10 hours for teens ages 13–18 (Paruthi S et al, J Clin Sleep Med 2016;12(6):785–786; Hirshkowitz M et al, Sleep Health 2015;1(4):233–243), many kids do not get these amounts. Fifty-eight percent of middle school students and 73% of high school students experience short sleep duration, with girls more sleep deprived than boys (76% vs 70%) (Wheaton AG et al, MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67(3):85–90).

Consequences of sleep deprivation in adolescents

A meta-analysis with over 500,000 participants found an inverse relationship between sleep duration and suicidality in adolescents. The risk of suicide plans decreased by 11% for every one-hour increase in sleep duration (Chiu HY et al, Sleep Med Rev 2018;42:119–126). Other research linked sleep deprivation in adolescents to automobile accidents and cognitive difficulties (Mason GM et al, Sleep Med Rev 2021;57:101472). Inadequate sleep may mimic ADHD and aggravate mood disorders. This can lead to a vicious cycle since medications commonly prescribed for ADHD often interfere with sleep. Lack of sleep also leads to greater risk-taking behavior, including substance use, and is associated with obesity, diabetes, sports injuries, and poor academic performance.

Assessing sleep problems in children and adolescents

There are four essential components of sleep history that you should review when assessing a sleep problem: 1. Sleep amount; 2. Sleep quality; 3. Sleep timing; and 4. State of mind related to sleep.

Sleep amount

Pin down how much sleep your patient is getting. Sleep-deprived adolescents are grumpy, have difficulty concentrating, and often sleep in excessively on weekends. Younger children and adults rarely do this. The patient’s recall may be inaccurate, so ask families to keep a daily record over at least a couple of weeks or use electronic sleep tracking devices such as wearables or smartphone-based applications. Although electronic sleep trackers are far from perfect, they can show trends in sleep. Some versions have been recently validated, including Fatigue Science ReadiBand, Fitbit Alta HR, Garmin Fenix 5S, and Garmin Vivosmart 3 (Chinoy ED et al, Sleep 2021;44(5):zsaa291).

Sleep quality

Get a sense of how effectively your patient is sleeping. Kids may sleep poorly despite adequate sleep time. Children who snore or sleep with their mouth open may have sleep apnea—the more they sleep, the less they are breathing. If you suspect sleep apnea or some other physiological disorder, contact the patient’s primary doctor to arrange a sleep assessment. Note that home-based sleep studies are not well validated in children or adolescents, and they are not typically reimbursed by insurance companies.

Sleep timing

Figure out when your patient sleeps. Sleep timing may reveal a circadian sleep disorder. The circadian system synchronizes biological rhythms to the day/night cycle. It’s harder for people to simply “go to bed earlier” unless they are very sleep deprived. Teens may find it easier to go to bed later and sleep later when possible rather than falling asleep earlier, but sleeping in or oversleeping in a child is a sign of sleep deprivation. The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted kids’ sleep, with classes alternating between virtual and in-person lessons and changing school start times. Establish a consistent wake-up time first to anchor the circadian system and make nighttime sleep easier.

State of mind

Ask who prompted the patient to come see you. Was it the parents’ idea or the child’s? Parents may recognize the connection between sleep and other problems. Children or teens who want help with sleep may be suffering from internalizing problems such as depression or anxiety that are harder for parents to recognize. Determine the child’s motivation to go to sleep and get out of bed. Do they look forward to going to sleep? Are they dreading the next day? Waking up is biological, but getting out of bed is volitional. I explain to my patients and their families that their lives are reflected in their sleep, and vice versa.

As you assess Sasha’s sleep, you learn that she gets plenty of exercise, does not drink caffeinated beverages, and avoids electronics after dinner. On weekends Sasha tries to catch up on sleep, often sleeping until early afternoon.

Techniques to improve sleep: CBTi

Conversations about sleep often center on sleep hygiene rules such as “turn off and put away the electronics two hours before bed” and “don’t lay awake in bed.” Patients, parents, and clinicians are aware of these rules. But according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s clinical practice guidelines, relying solely on sleep hygiene is usually ineffective (Edinger JD et al, J Clin Sleep Med 2021;17(2):255–262). A more comprehensive approach is cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTi), which has a good track record in adults and has been adapted for children and teens. It may be more helpful for our patients.

CBTi is cognitive behavioral therapy that is specific to the thoughts, behaviors, and emotions related to sleep (Mindell JA et al, Sleep 2006;29(10):1263–1276). Referral to a more specialized practitioner is challenging, as the small number of these clinicians cannot meet the clinical demand. You can use basic CBTi in your office, but keep in mind that it can take weeks to implement.

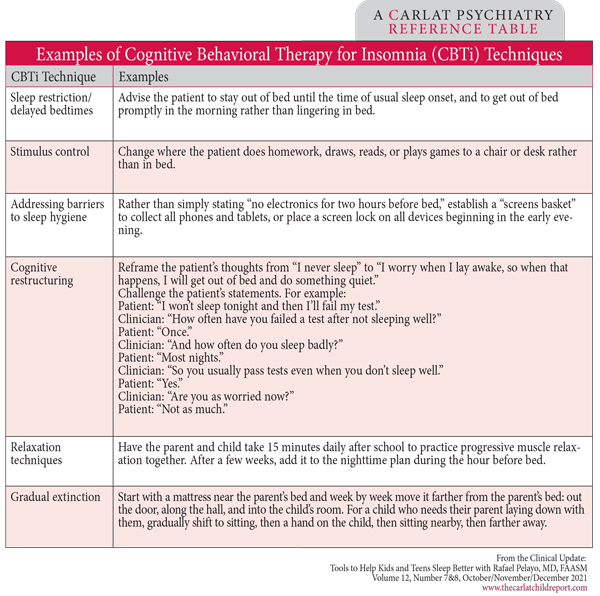

Here are some typical CBTi techniques (see box below):

- Sleep restriction/delayed bedtimes:

Assess how much time the patient spends actually sleeping in bed, and adjust to reduce the amount of time in bed awake. The goal is to make the time devoted to sleeping more efficient.

- Stimulus control:

Strengthen the connection between bed and sleep by changing the location of other activities so that the bed is only used for sleeping.

- Gradual extinction:

For a young child in a parent’s bed, take a slow stepwise approach to moving the child to their own bed. More steps are more effective.

- Cognitive restructuring:

Identify distorted thoughts about sleep and challenge, replace, or reframe them.

- Address barriers to sleep hygiene:

Individualize the implementation of usual recommendations. For example, create a workable plan for restricting evening electronics.

- Relaxation techniques:

Teach progressive muscle relaxation (PMR), deep breathing, and visualization. To gain proficiency, the patient should practice these techniques while they are not trying to sleep. Many scripts and videos cover PMR for kids. See www.tinyurl.com/rfk4axu6 and www.tinyurl.com/ayruumtk for some resources.

Table: Examples of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBTi) Techniques

You determine that Sasha is not getting enough sleep during the school week and that she and her family need to prioritize her sleep. As part of the initial plan, you talk with Sasha and her family about sleep deprivation and tell her parents to have her stop sleeping in on weekends. You explain that this will make Sasha’s sleep more predictable and help her get more sleep during the week.

Medications?

There are no FDA-approved hypnotics for children. We recommend avoiding hypnotic medications when possible in children and teens. Off-label use of medications such as guanfacine or clonidine is best done as a time-limited approach. Medications may have a role in insomnia, narcolepsy, parasomnias, and sleep-related movement disorders; however, parents and healthcare providers often use hypnotic medications without adequate application of behavioral techniques and without taking into account circadian modulation of alertness.

Keep in mind that people are more alert for about two hours before sleeping. If a medication shortens sleep latency by only 20 or 30 minutes, patients may report that the medication “makes things worse” or that it causes a child to act strangely, perhaps experiencing hypnagogic hallucinations. This can occur especially if the family gives the medication early because of fear of next-day sedation. Similarly, giving a low dose may result in the child being disinhibited but not falling asleep. The same medication given at a more appropriate circadian time and/or dose may be effective. Also note that if a child is not expecting or wanting to sleep, they may resist the drowsy feelings or become upset. Consider short-term use of a melatonin supplement (1–3 mg) 90 minutes before bed.

Sasha returns in three weeks and reports having more energy during the day. She gets about 7.5 hours of sleep per night, her homework is done earlier, and her grades are up. Her parents are glad to avoid using medications and will let you know if there are difficulties in the future.

CCPR Verdict: Sleep problems have lifelong complications. The sleep medicine field has matured and can help most of our patients. Screen for sleep disorders in all patients at every visit. Consider using CBTi to effect meaningful change rather then relying on generic sleep hygiene rules, and try to avoid using medications. If you need to refer to a sleep specialist in behavioral sleep medicine, try: www.behavioralsleep.org/index.php/united-states-sbsm-members