Antipsychotic Polypharmacy: Helpful or Harmful?

The Carlat Psychiatry Report, Volume 14, Number 1, January 2017

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/tcprv14n1/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Antipsychotics | Bipolar Disorder

Kelly N. Gable, Pharm.D

Associate Professor, SIUE School of Pharmacy

Psychiatric Care Provider, Places for People

Dr. Gable has disclosed that they have no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Daniel Carlat, MD

Editor-in-Chief, Publisher, The Carlat Report.

Dr. Carlat has disclosed that he has no relevant relationships or financial interests in any commercial company pertaining to this educational activity.

Prescribing two antipsychotics to a single patient is a common practice in clinical settings. One study estimated that up to 50% of psychiatric inpatients are receiving antipsychotic polypharmacy (Faries D et al, BMC Psychiatry;5:26). Increasingly, we are being scolded for this practice. A variety of guidelines discourage polypharmacy, and recent studies have documented that we are often not following such guidelines.

Clearly, psychiatrists aren’t combining drugs in order to be obstinate, to cost the system more money, or to harm patients. We’re doing it because we want to make our patients feel better, and in many cases a single drug is not doing the trick. Studies indicate that the patients who are more likely to be prescribed multiple antipsychotics are younger, single, unemployed, and male; they also present with more severe psychotic symptoms. Patients with frequent hospital admissions, involuntary admissions, and those prescribed long-acting injectables (LAI) are also more likely to eventually be on two antipsychotics at the same time (Fleischhacker WW and Uchida H, Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2014;17(7):1083–1093).

If possible, stick with a single antipsychotic. But if the situation seems to call for polypharmacy, here are some factors to guide your decision-making. The published evidence base for any combination regimen is either slim or non-existent, so consider these to be commonsense guidelines drawn from clinical experience (when there are actual studies endorsing these practices, we cite them below).

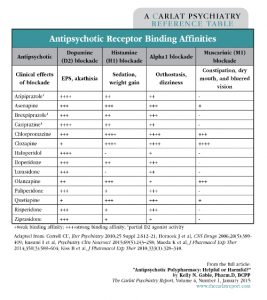

Consider the differing receptor-binding profiles of the many antipsychotics available for use (see table below). First-generation antipsychotics, such as Haldol, bind tightly to dopamine receptors and occupy the sites longer. Some second-generation antipsychotics, especially quetiapine and clozapine, are known to have a quick “on-off” effect, meaning they dissociate from the dopamine receptor quickly (McIntosh DM et al, The Canadian Journal of Diagnosis 2011; (4):33–44). How does receptor affinity translate to clinical practice? Generally, longer and tighter binding to D2 will trigger more extrapyramidal side effects (EPS), whereas quick on-off binding translates to minimal or no risk of EPS development. Also take note of other receptor binding activity, such as histamine, alpha, and muscarinic, all of which are described in the table. Using this information, for example, you would predict that two highly histaminergic or muscarinic blocking antipsychotics, like clozapine and olanzapine, will likely lead to a very tired, cognitively impaired, and constipated patient.

Table: Antipsychotic Receptor Binding Affinities

Some common polypharmacy scenarios

Our clinical experience indicates that there are a few common scenarios leading to multiple antipsychotics. We’ll describe each in turn, and comment on which ones are more or less reasonable.

1) Attempting to gain more rapid control of psychotic symptoms

Current treatment: quetiapine or other low-potency agent. Potential addition: haloperidol 1–2 mg every 6 hours PRN agitation, po or IM, depending on situation and setting.

This scenario is often appropriate. Haloperidol can be used to control acute agitation on top of an atypical antipsychotic, and it frequently works. One could also use other higher-potency antipsychotics, such as aripiprazole, risperidone, or paliperidone. Overall, we suggest limiting such combinations to short term use (1–4 weeks). Too many antipsychotics with complicated dosing schedules will only lead to difficulty with treatment adherence.

2) Refractory cases

Current treatment: clozapine. Potential addition: risperidone 1 mg daily due to poor symptom control: low-potency oral agent.

Clozapine is the clear favorite when it comes to the treatment of refractory schizophrenia. But what do we do when clozapine isn’t enough? Adding risperidone to clozapine has become a favorite of clinicians, based on two placebo-controlled trials (Freudenreich O et al, J Clin Psychiatry 2009;70(12):1674–1680 and Josiassen RC et al, Am J Psychiatry 2005;162(1):130–136), though one larger trial showed no beneficial effect of adding risperidone (Honer et al, N Engl J Med 2006;354(5):472–482). We suggest trying this option only after a solid 12-week trial of clozapine monotherapy at therapeutic doses of 300–900 mg daily.

3) Management of acute symptom exacerbations during treatment with an LAI antipsychotic

Current treatment: paliperidone LAI IM q 4 weeks, or other LAI. Potential addition: low-potency oral agent.

Your patient has a worsening of psychosis, despite taking the maximum recommended dose of an LAI. There is no evidence-based guidance on to how to approach this problem. You will probably be reluctant to discontinue the shot if your patient has responded well to it in the past. You could consider shortening the interval of the injection first (eg, move from every 4 weeks to every 3 weeks). When you do add on a second antipsychotic, try one with a differing receptor-binding profile (see table). Be mindful of worsening EPS and hyperprolactinemia with these combinations. Ensure that you reevaluate the regimen routinely, and attempt to remove the additional oral antipsychotic periodically.

4) Treatment of co-occurring insomnia

Current treatment: risperidone. Potential addition: quetiapine 50 mg q HS.

It is quite common for psychiatrists to prescribe quetiapine for insomnia, agitation, and anxiety (Philip NS et al, Ann Clin Psychiatry 2008;20(1):15–20). A survey of Medicaid prescribing from 2004 indicated that quetiapine was the most likely antipsychotic to be co-prescribed long-term with other antipsychotics (Ganguly et al, J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65(10):1377–1388). Once you have maxed out your dopamine blocking threshold (for Haldol or Prolixin, this is between 10 and 20 mg a day), it does make sense to consider the addition of a low-potency, sedating antipsychotic—if the problem being targeted is psychosis. For a patient with insomnia, consider a sleep study referral, or a trial with one of the many dedicated hypnotics, such as benzodiazepines, non-benzos, melatonin, and others. Our suggestion would be to avoid antipsychotic polypharmacy here if you can. Quetiapine, while sedating and calming, is also likely to cause or exacerbate troublesome metabolic side effects such as weight gain and diabetes.

5) Treatment of antipsychotic-induced adverse effects

Current treatment: risperidone. Potential addition: aripiprazole to lower prolactin levels induced by risperidone.

There are varying opinions on the appropriateness of using an antipsychotic to treat antipsychotic-induced side effects. There are several studies highlighting the effectiveness of aripiprazole at reducing prolactin levels induced by other antipsychotics (Kane JM et al, J Clin Psychiatry 2009;70(10):1348–1355). This is due to its dopamine agonist properties. The biggest concern with this combination is the financial burden associated with its use, though aripiprazole will become much cheaper with time now that it is available as a generic. This combination should be considered for patients who have had a positive response to risperidone therapy but have significant hyperprolactinemia.

There are also limited data describing the benefit of adding aripiprazole to clozapine therapy to reduce metabolic-associated adverse effects. Adding aripiprazole to clozapine (Fan et al, 2013) or olanzapine (Henderson et al, J Clin Psychopharmacol 2009;29(2);165–169) has resulted in weight loss and LDL cholesterol lowering; however, you may not see a robust change in psychosis (Kane JM et al, J Clin Psychiatry 2009;70(10):1348–1355).

6) Caught in the cross-taper/titration

Current treatment: lurasidone (tapering due to poor response). Potential addition: olanzapine, with plan to titrate up while tapering lurasidone, but patient has a positive response to both treatments together.

Even great clinicians can be a victim of the taper/titration trap. All you really know here is that lurasidone didn’t cut it by itself, and when you added olanzapine, the patient got better. So, was it the olanzapine or was it the combo? Sometimes it is just easier to leave well enough alone and not risk symptom relapse. Despite this, your patient deserves a try with olanzapine solo before keeping the combination going long-term. There are just no good data to support this kind of duo, and again, the risk of side effects continues to grow. An adequate taper/titration schedule should really be done within 8 weeks.

TCPR Verdict: Combining antipsychotics can be helpful in some situations, but monitor closely for side effects and try to reduce back to monotherapy if possible.