Assessing Complex PTSD

The Carlat Psychiatry Report, Volume 15, Number 12, December 2017

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/tcprv15n12/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Free Articles | PTSD

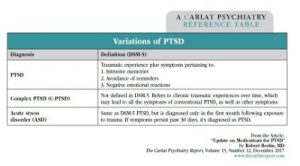

Arielle Schwartz, PhD Licensed clinical psychologist in private practice in Boulder, CO. Author of The Complex PTSD Workbook: A Mind-Body Approach to Regaining Emotional Control and Becoming Whole. Dr. Schwartz has disclosed that she has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity. TCPR: We’ve been hearing more the last few years about the concept of complex PTSD. I know that there are similarities with conventional PTSD—which is covered in the DSM-5—but can you explain to our readers how complex PTSD is different from conventional PTSD? Dr. Schwartz: The first thing that I would say is that complex PTSD can sometimes be harder to spot and diagnose, because when we’re looking for symptoms of conventional PTSD, we’re often looking for that first criterion: Has there been a single event that your patient would consider traumatic? In general, was the patient exposed to any major negative event? But with complex PTSD, it’s about a period of exposure to many sequential traumatic events, or it’s a chronic exposure to high stress, where there is either no real escape from the stress or a perception that there is no way to leave the situation. One thing that can make complex PTSD more difficult to diagnose is that there may not be a single traumatic event. In addition, it can be challenging to differentiate a diagnosis from other masking or coexisting conditions (Knipe J. EMDR Toolbox: Theory and Treatment of Complex PTSD and Dissociation. New York, NY: Springer Publishing; 2015). TCPR: Can you give us some examples of the kinds of events that would cause complex PTSD? Dr. Schwartz: Sure. I’d start by saying that sometimes the void or lack of something can lead to complex PTSD, and that there isn’t specifically something that has caused it. For example, PTSD could have resulted after a child grew up in a home where basic needs were provided for, but where there was a lack of attunement, attachment, and understanding of this child. That can give the child a deep sense that “I don’t belong or feel loved,” that “I shouldn’t be here and there’s something wrong with me.” This can have a crossover to what we think of as attachment disorder or developmental trauma, and in those cases what we’re looking at really is neglect. Chronic neglect can occur in different scenarios, such as growing up with a caregiver who had a significant mental illness, such as severe depression or schizophrenia, or growing up with a parent who was repeatedly incarcerated. Variations of PTSD TCPR: In mentioning attachment disorder and developmental trauma, is this the part of the patient interview where we might ask if the patient was abused physically, verbally, or sexually as a child? Are those the kinds of questions that will elicit a history consistent with complex PTSD? Dr. Schwartz: Absolutely. I think those questions get at it. In general, if we look at tools such as the ACE (Adverse Childhood Experience) questionnaire, then it broadens out. It’s also not just about direct child abuse; we also want to find out if patients were witness to domestic violence in their home over a period. Defining neglect can be difficult. And keep in mind that complex PTSD is not always the result of a childhood trauma. It can also result from living in an ongoing abusive relationship as an adult, where there’s chronic exposure to stressful situations (Felitti VJ et al, Am J Prev Med 1998;14(4):245–258). TCPR: You mention the ACE questionnaire. For our readers who aren’t familiar with that, can you tell us more? Dr. Schwartz: It was developed to understand the impact of adverse childhood events, such as abuse or exposure to domestic violence or neglect. The tool has been around since the mid-1980s, and it’s a 10-question quiz. Through a point scoring system, you can then connect those experiences to the potential for developing mental health and other problems in adulthood. For example, one question is, “Did a parent or other adult in the household often push, grab, slap, or throw something at you?” You can get more information on the ACE questionnaire from the American Academy of Pediatrics (http://bit.ly/2yRxsQe). TCPR: So, let’s say that we’re talking to a patient, and we get a sense that trauma went on for a period. How do we determine whether the diagnosis of complex PTSD is appropriate? Dr. Schwartz: In many ways, the symptoms are like traditional PTSD: things such as hyperarousal, flashbacks, difficulty sleeping, re-experiencing in some way or another. We will also look for avoidance symptoms in which clients isolate or avoid certain situations that are reminiscent of their trauma. Sometimes, the symptoms are present, but patients don’t know why or what it is that they are avoiding, especially if the trauma occurred when they were very young. I think that’s why it takes a lot of careful detective work to come to an accurate diagnosis. I’ve had many clients over the years who have been diagnosed, sometimes accurately, with comorbid disorders such as bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, and ADHD. Until complex PTSD was really understood, sometimes those other disorders were the closest diagnoses that could be found. TCPR: I see, but I’m still not totally clear on how to make the diagnosis. Can you give us a clinical case that might illustrate further? Dr. Schwartz: Sure. I’ll share a little bit about a woman who was referred by her psychiatrist. She had been treated for many years for bipolar disorder, but had never really done a deep dive in psychotherapy. When she came in and we started to go into more of a thorough developmental history, there was nothing glaring on the first review of her childhood. There was a lot of “my childhood was relatively normal; things were fine.” But as we continued to talk about things, we learned that her dad was out of the home a lot because of work. When he did come home, he would drink a lot, and he would rage. I also learned that there were five children in the home, and that her mom was never really prepared to handle the stress of taking care of that many kids. The patient was also the second youngest in her family, and there was some middle child syndrome going on too. TCPR: Interesting. So, what else did you learn? Dr. Schwartz: All of this was stressful for her, and she kept all of that to herself for many years. Eventually, it had developed into an eating disorder in her teenage years, and had rolled over into what she described as a tremendous amount of self-hatred. By her early 20s, she was diagnosed as bipolar II due to her symptoms of anxiety, rage, “acting out” sexually, and over-spending. As we started to unpack more about her childhood, we learned that there were many deep-seeded feelings of anger, resentment, and hurt that she had kind of swallowed or pushed down to make it through a pretty stressful upbringing. TCPR: And how are you treating her? Dr. Schwartz: We have been tackling the psychological side of all of this, and I’m working closely with her psychiatrist. She has actually been able to taper down on her medication to where she is minimally medicated at this point. Early on in treatment, with the concern that her medications weren’t working, she would call her psychiatrist when there was rage or anxiety. Now she recognizes that her underlying emotions often get funneled into rage. She knows to call me when she feels that rage emerging. TCPR: What are some of the specific therapies you’d recommend for treatment of complex PTSD? Dr. Schwartz: Generally, so that you know how to work within the context of a relational framework, I recommend that you develop a pretty broad clinical toolbox. What we know about psychotherapy is that the strongest common factor of therapeutic efficacy is a positive therapeutic rapport (Shapiro F, Perm J 2014;18(1):71–77). In my opinion, and no matter your therapeutic approach, this involves awareness of how to work with dynamics of transference and countertransference. Personally, I draw upon EMDR (eye movement desensitization and reprocessing) therapies. But I also use cognitive behavioral therapy and dialectical behavioral therapy, in conjunction with some mindfulness work. I’ll use elements of cognitive behavioral therapy to help patients recognize thought distortions, address unhelpful patterns, and develop more helpful thought patterns. But I won’t typically do traditional exposure. When doing exposures, I will use an EMDR approach, with its desensitization element. Talk therapy alone typically is not going to get to the root of the physiological dysregulation that goes along with complex PTSD. TCPR: So, how would you define EMDR and how do you use it? Dr. Schwartz: I’ll describe several working mechanisms. One is the adaptive information processing (AIP) component, which is basically the inherent drive toward health that exists in every individual. The aim of EMDR is to help the individual connect to that drive, which is done through an eight-phase model. Often, most people associate EMDR specifically with Phase 4, which is the desensitization protocol, but all successful trauma treatment models are phased models, and the initial phases are always going to be about preparation. EMDR places a tremendous focus on the importance of preparing someone for desensitization and exposure (van der Kolk B. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York, NY: Viking Press; 2015). When patients first experienced trauma, they didn’t have the resources to deal with it. If they don’t have the resources now, they’re going get overwhelmed again. So, we focus on the front end, helping clients feel that they have choice and control over what they’re thinking about. TCPR: And what is the result? Dr. Schwartz: That then develops into a key working mechanism of EMDR therapy, which we refer to as the dual awareness effect. Dual awareness means that I can be present and oriented with my senses in the here and now, and can recognize that I’m safe while I turn my attention to there and then and the traumatic incidents that happened to me. What often happens, especially with complex PTSD, is that there can be a flooding of physiological arousal. If someone has a tendency toward dissociation, the person might get overwhelmed very quickly, and we don’t want to lose dual awareness. So, as soon as that arousal state feels like it’s too much, we then return awareness to here and now. You say to the patient: “You’re sitting in this room with me. Look around the room. Can you recognize that you’re safe now?” If the patient replies, “Yes, I can,” we can now bring our attention back to the traumatic incident, and we’ll work a little bit at a time. Sometimes this is referred to as pendulation, or a titration model. TCPR: And where do the eye movements, or the other kind of movements, come into the model? Dr. Schwartz: The eye movements and other forms of bilateral stimulation, such as bilateral sounds or bilateral music, facilitate the dual awareness state. EMDR therapy also incorporates bilateral stimulation in the form of eye movements. Therapists move their fingers from side to side in front of the client’s face, and the client tracks this movement with the eyes. Bilateral stimulation can be experienced with tones in the ears or pulsers held in the hands. TCPR: Any other thoughts on why the complex PTSD concept isn’t fully accepted yet? For example, it’s not in the DSM-5, right? Dr. Schwartz: Correct, but I believe that it should be. I think including complex PTSD in the DSM-5 would reduce a lot of misdiagnoses. More and more people are getting this diagnosis from clinicians, who are familiar with it from psychiatrists, from their doctors, who have been educated to look for complex PTSD. But in terms of providing a diagnosis, we still must resort to the traditional PTSD diagnosis, because it’s the closest we have. A DSM-5 committee considered adding both complex PTSD and developmental trauma to the manual, but decided against it because these seemed too similar to other disorders. TCPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Schwartz.