Getting Uncomfortable with Esketamine

The Carlat Psychiatry Report, Volume 18, Number 1, January 2020

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/tcprv18n1/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Antidepressant Augmentation | Antidepressants | Brain Devices | Depression | Depressive Disorder | ECT | Esketamine | Free Articles | Ketamine | Neurotoxicity | Novel Medications | rTMS | Suicidality | TMS | Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation | Treatment-Resistant Depression

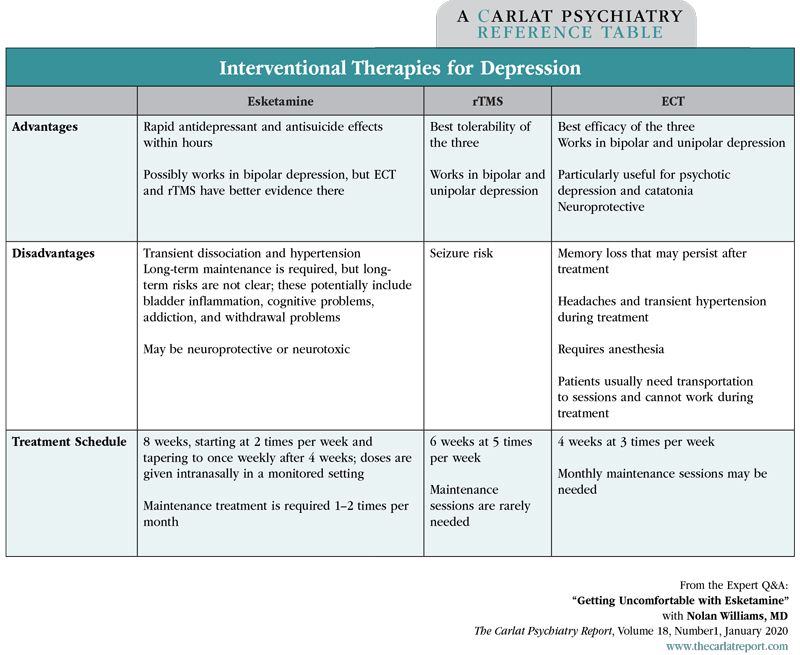

Director of the Brain Stimulation Lab and Interventional Psychiatry Clinical Research Program; Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at Stanford University, CA. Dr. Williams has disclosed that he has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity. Esketamine (Spravato) was approved for treatment-resistant depression in 2019. In this interview, Dr. Williams (who has no relationship with Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc) addresses some lingering doubts that have been raised about the medicine. TCPR: Where does esketamine fit in the list of interventional therapies for depression, like repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)? TCPR: How is esketamine different from ketamine? TCPR: Is anyone developing arketamine for depression? TCPR: You alluded to some risks with esketamine. What would steer you away from it? TCPR: And I guess that abuse potential is greater when we move toward long-term use. TCPR: What if the patient is discharged from the emergency room? Could the suicidality return when the dose wears off in a few days? TCPR: What do we know about esketamine withdrawal? TCPR: You’re suggesting that a drug-withdrawal effect might be behind those suicides. Do we know anything about the mechanism of action there? TCPR: Sounds like more research is needed there, but it’s concerning. TCPR: Does it concern you that we haven’t found anything to prevent depressive relapse after a course of ketamine/esketamine? TCPR: Relapse is a problem after ECT as well. What can we do there? TCPR: What are the relapse rates after rTMS? TCPR: So from a long-term perspective, rTMS seems better. What about in the short term? Table: Interventional Therapies for Depression TCPR: So for now, if patients respond to esketamine or ketamine, they’re likely to require continuation treatments. What are ketamine’s long-term risks? TCPR: That explains the song about ketamine by Trampolene: “Your mind might be fine, but your bladder is shredded.” Is the mind really fine after long-term ketamine use? TCPR: You’ve pointed out a lot of gaps in our knowledge about esketamine. What type of research needs to be done? TCPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Williams. Listen to this discussion in this episode of The Carlat Psychiatry Podcast.

Nolan Williams, MD

Nolan Williams, MD

Dr. Williams: For my practice, right now ketamine and esketamine have two roles. One is for people who don’t respond to conventional rTMS—that is, rTMS with the FDA-approved methods—and either cannot or don’t want to try a course of ECT. About half of people who try conventional rTMS don’t benefit from it, so this is a fair number of people we’re talking about. The second is in emergency settings, where there’s a need for rapid relief of suicidality. For example, it might be useful with a patient who needs a sitter in the ER because of severe suicidal urges.

Dr. Williams: Ketamine is made up of 2 isomers: (R)-ketamine (aka arketamine) and (S)-ketamine (aka esketamine). In this interview, I’ll use the phrase “ketamine/esketamine” when referring to both compounds. These are like right- and left-handed scissors: They look the same, but if you’re right handed and have ever tried to use left-handed scissors, you know they’re not. So we can’t completely translate the ketamine findings to esketamine, especially since there’s evidence that the other isomer—arketamine—may be the more potent one. In animal models of depression, arketamine has more potent and longer-lasting antidepressant effects, less rewarding effects, less neurotoxicity, and fewer side effects (Yang C et al, Transl Psychiatry 2015;5(9):e632). It’s too early to say how ketamine and esketamine compare clinically, but a head-to-head study is underway that will shed light on that (Correia-Melo FS et al, Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97(38):e12414). Ketamine also has an active metabolite—norketamine—so it’s a complex drug.

Dr. Williams: Yes. Perception, a Japanese pharmaceutical company, owns the patent and just started clinical trials in 2019. Janssen owns the esketamine patent, and the patent for ketamine is long expired, which is why these companies are pursuing the isomers.

Dr. Williams: Ketamine/esketamine may have an abuse liability. There have been cases where patients get exposed to ketamine in an office setting and then start to order it off the internet. One academic center even shut down its ketamine program because of concerns about drug-seeking behavior (Newport DJ et al, Depress Anxiety 2016;33(8):685–688). These problems were not reported in the esketamine trial, but the investigators screened out the kinds of patients who are at risk for abuse. On balance, ketamine has some promising data as a treatment for addictions, like cocaine and alcohol (Dakwar E et al, Mol Psychiatry 2017;22(1):76–81). So this could go either way.

Dr. Williams: That is possible, although more studies are necessary. That’s why I’m more comfortable with single-dose treatment of IV ketamine, like the way it might be used in the emergency room for suicidality. That’s analogous to single-dose opioid administration for acute pain: If someone breaks their leg, they go to the ER and they’ll probably get an opiate, but that one-time use is unlikely to lead to addiction. We also have more data on the one-time use because that’s how most of the ketamine studies were done.

Dr. Williams: You’d want that patient followed closely like in a partial hospital program or even a ketamine/esketamine treatment center. We deal with the same issue with hospitalization. Many patients are hospitalized for 3 days, or even 1 day, and discharged as soon as their suicidal thinking resolves. Those first few months after hospital discharge are a high-risk period for suicide. The question you’re raising is how long the benefits of single-dose IV ketamine or intranasal esketamine will last. A separate issue is whether there’s a withdrawal phenomenon when ketamine/esketamine wears off. I’m not so worried about that after one dose, but it is a concern in someone who has been taking ketamine/esketamine regularly for weeks or months.

Dr. Williams: There’s a possibility that patients could become more suicidal after the drug is discontinued. We don’t know this for sure, but there’s a signal in the FDA-registration studies. It wasn’t statistically significant, so the drug got approved, but there were 6 deaths in the study, and this occurred after the open-label esketamine phase, so they had all been getting active treatment. Three of them were definite suicides, and these suicides occurred after their last esketamine dose: 4 days, 12 days, and 20 days after (www.fda.gov/media/121376/download). The FDA concluded that the deaths may have been due to the severity of the depression rather than the drug. However, we don’t see suicides with that kind of frequency in studies of rTMS or ECT that enroll a similar population. Furthermore, the patients who died by suicide had no signs of suicidality in detailed assessments done during the study, which suggests it may have come on during the withdrawal period.

Dr. Williams: Yes. We had a surprising finding last year with IV ketamine that might explain it. Our group showed that ketamine’s antidepressant effects are cancelled when you block opioid receptors with the opioid antagonist naltrexone, which means that ketamine probably has direct or indirect opioid properties (see TCPR, June/July 2019). Now, does that mean that there’s an opioid-like withdrawal when esketamine is stopped? We don’t know, but it’s possible. Ketamine also has glutamatergic effects on the NMDA receptor, but I don’t think that NMDA withdrawal would cause a problem. Otherwise we’d be seeing suicidality after patients stop memantine (Namenda).

Dr. Williams: Yes. We just received a grant from the American Suicide Foundation to investigate whether buprenorphine can prevent this problem and extend IV ketamine’s antidepressant effects after it is stopped. Like IV ketamine, buprenorphine has positive studies in treatment-resistant depression and in suicidality, but there’s no known risk or even a signal of suicide during its withdrawal (see TCPR, February 2019).

Dr. Williams: Yes. So far the only thing that works is more ketamine/esketamine, which raises questions about potential tolerance, withdrawal, and addiction. Again, we don’t know that those things are happening; we just don’t have enough studies to rule them out. Riluzole was tried as a continuation agent, which like ketamine has glutamatergic effects, but it did not work (Mathew SJ et al, Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2010;13(1):71–82). So it will be interesting to see if going through the opioid receptor continues the effects.

Dr. Williams: ECT has a rich literature on this, and there’s good evidence that nortriptyline or venlafaxine can prevent episodes after a course of ECT. Lithium can also work, either alone or as antidepressant augmentation. Another strategy is to start an antidepressant that the patient responded to in the past and use that for prevention (Gill SP et al, J ECT 2019;35(1):14–20). Most patients do require maintenance ECT, at least temporarily. Those booster sessions are usually given 1–4 times a month and can be slowly tapered.

Dr. Williams: A typical course of rTMS is 5 treatments a week for 6 weeks. Each treatment takes 30–60 minutes. Afterwards, about two-thirds of patients remain well for up to 6 months without any booster sessions. If we add in booster sessions, the rate of sustained benefits goes up to 85%–90%. So rTMS appears to be more durable than esketamine, which requires booster treatments to keep it working. Also, keep in mind esketamine is an antidepressant augmentation strategy, so the patients remained on an antidepressant after stopping it. In the case of rTMS, some of the patients who stayed well were not taking any antidepressants.

Dr. Williams: Ketamine and esketamine’s main advantage is that they can work quickly, within hours, which is why it has a role in the ER. rTMS takes 4–6 weeks to work. Otherwise, rTMS and ketamine have comparable remission rates. They haven’t been compared head to head, but both have remission rates of 20%–30%. ECT is the one that shines here. A recent meta-analysis estimated the remission rate on ECT at 48%. So ECT wins for efficacy, conventional rTMS wins for safety and tolerability, and esketamine wins for speed.

Dr. Williams: The biggest one is bladder inflammation or cystitis, which has been seen in people who are addicted to ketamine. It is unclear if this is a risk with therapeutic doses of esketamine or IV ketamine, and it may in fact not be. That was first reported in people who were abusing ketamine in Malaysia, and it’s likely they were taking much higher doses than what we use clinically (Lee P et al, Malays Fam Physician 2009;4(1):15–18). Since those reports came out, they’ve clarified the mechanism a bit, and it seems that ketamine abuse can lead to cellular death in the bladder and fibrotic changes in the nerves that innervate the bladder. It’s a significant problem; about 50% of ketamine abusers are affected (Jhang JF et al, Neurourol Urodyn 2019;38(8):2303–2310).

Dr. Williams: Not if it’s abused. Ketamine has the potential to be neurotoxic or neuroprotective, and it probably depends on the frequency of use. Long-term ketamine abuse has been associated with cognitive problems and loss of brain tissue in the frontal lobes and left temporoparietal regions (Liao Y et al, Brain 2010;133(7):2115–2122). The effect is likely due to ketamine because it is dose dependent, and it’s been replicated in animal studies with careful controls. On the neuroprotective side, ketamine does increase brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). It may be that a bit of ketamine is fine and a lot is not. There have been no reports of neurotoxicity with clinical use of ketamine and esketamine, although we haven’t really been looking for that.

Dr. Williams: I would love to see a head-to-head trial of esketamine and conventional rTMS. If esketamine were to beat conventional rTMS in long-term safety and efficacy, that would likely change minds about its use.