How to Treat ADHD in Bipolar Disorder

The Carlat Psychiatry Report, Volume 19, Number 11&12, November 2021

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/tcprv19n11-12/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: ADHD | Alpha Agonists | Amphetamines | ArModafinil | Atomoxetine | Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder | Bipolar Disorder | Bipolar II | Comorbidity | Guanfacine | methylphenidate | Modafinil | Nuvigil | Pharmacology | Provigil | Psychopharmacology | Psychopharmacology Tips | stimulant | Stimulants

Chris Aiken, MD.

Editor-in-Chief of TCPR. Practicing psychiatrist, Winston-Salem, NC.

Dr. Aiken has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Patients with bipolar disorder often present with cognitive complaints. Our October 2021 issue laid out a diagnostic plan for these symptoms, and in this article, I’ll cover some treatment approaches for patients with a DSM-based ADHD-bipolar comorbidity (ie, the ADHD symptoms began in childhood and persist after the mood episodes have stabilized).

Stimulants in bipolar disorder

Stimulants are the mainstay treatment in ADHD, but they carry several risks that are pertinent to bipolar disorder: mania, psychosis, insomnia, substance abuse, and neurotoxicity. Overt mania is rare on them, and mood stabilizers lower that risk significantly—however, lamotrigine, which is not anti-manic, doesn’t count here (Viktorin A et al, Am J Psychiatry 2017;174(4):341–348). More common is milder symptomatic worsening. Around one in seven patients with bipolar disorder and ADHD experienced worsening of mood, irritability, or anxiety on stimulants—even with mood stabilizers in place, based on results from six small clinical trials.

These risks may be a little less pronounced with methylphenidate than the amphetamines (eg, Adderall, Dexedrine, Vyvanse). Amphetamine has been used as an animal model of mania since 1978, and it is twice as likely to trigger psychosis than methylphenidate (Moran LV et al, N Engl J Med 2019;380(12):1128–1138). Methylphenidate, in contrast, was once thought to treat mania by stabilizing mental arousal, and although this theory did not pan out in a recent trial in acute mania, methylphenidate at least did not worsen mania in that brief, three-day, placebo-controlled trial (Hegerl U et al, Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2018;28(1):185–194). Methylphenidate also has a lower abuse potential, judging from its rewarding properties in preclinical studies. Finally, amphetamine has more neurotoxic properties than methylphenidate, such as depleting vesicular pools of dopamine (Moratalla R et al, Prog Neurobiol 2017;155:149–170, although this problem has only been documented in animal studies using high doses—eg, equivalent to amphetamine 140–700 mg/day in humans).

What about the benefits of stimulants in this population? Only three placebo-controlled trials looked at ADHD symptoms in patients with stable bipolar disorder, two of which were positive. These studies, which were conducted in children, were limited in size (total n = 63), duration (two weeks), and design (crossover instead of parallel group) (Zeni CP et al, J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2009;19(5):553–561).

The bottom line is that stimulants pose risks in bipolar disorder, so we’d be better off with safer alternatives when possible.

Nonstimulant options

My top choices for ADHD in bipolar disorder are the alpha-agonists (clonidine [Kapvay] and guanfacine [Intuniv]) and the modafinils (armodafinil [Nuvigil] and modafinil [Provigil]). The alpha-agonists are FDA approved in pediatric ADHD and improve executive functioning in various populations, including schizophrenia, substance use disorders, and ADHD (Arnsten AFT, Neurobiol Learn Mem 2020;176:107327). Modafinil came close to FDA approval in ADHD but was held back when a child developed Stevens-Johnson syndrome on the drug (a rare but real risk). Compared to the stimulants, these two classes of medications have smaller effects in ADHD, but they also have broader benefits in bipolar disorder.

The modafinils have been effective for bipolar depression in some, but not all, trials. The negative findings may result from the fact that they improve only energy, alertness, and attention, rather than the full depressive syndrome (see TCPR June/July 2020). The alpha-agonists, particularly clonidine, improve sleep, irritability, and anxiety in various populations. Neither of these nonstimulant options are neurotoxic, and the modafinils have neuroprotective effects, increasing synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus (Yan YD et al, Transl Psychiatry 2021;11(1):116). Regarding manic risk, the alpha-agonists did not cause or worsen mania in clinical trials, while the modafinils have both caused and treated mania in case reports (Hardy-Bayle MC, Encephale 1989;15(6):523–526; Schoenknecht P et al, Biol Psychiatry 2010;67(11):e55–e57).

Atomoxetine, viloxazine, and … lithium?

Although approved in ADHD, atomoxetine (Strattera) and viloxazine (Qelbree) are controversial in bipolar disorder because these antidepressant-like compounds can induce mania (Perugi G and Vannucchi G, Expert Opin Pharmacother 2015;16(14):2193–2204). Stimulants are usually better options than these, as their manic risk is at least balanced by a more substantial benefit in ADHD.

Surprisingly, lithium has a controlled study in adult ADHD without bipolar disorder where it worked as well as methylphenidate 40 mg/day on measures of ADHD, mood, and irritability (lithium levels were 0.5–0.7).

Omega-3s

For patients who prefer a non-medication approach, omega-3 fatty acids are a good place to start. This supplement improved bipolar depression and emotional and cognitive symptoms of childhood ADHD with a small effect size, according to meta-analyses of seven to eight placebo-controlled trials in each disorder (Kishi T et al, Bipolar Disord 2021 (Epub ahead of print); Chang JP et al, Neuropsychopharmacology 2018;43(3):534–545). Notably, omega-3s tended to work better in the ADHD studies when the dose was brought closer to the range used in the bipolar trials. (See the Treatments for ADHD in Bipolar Disorder table below.)

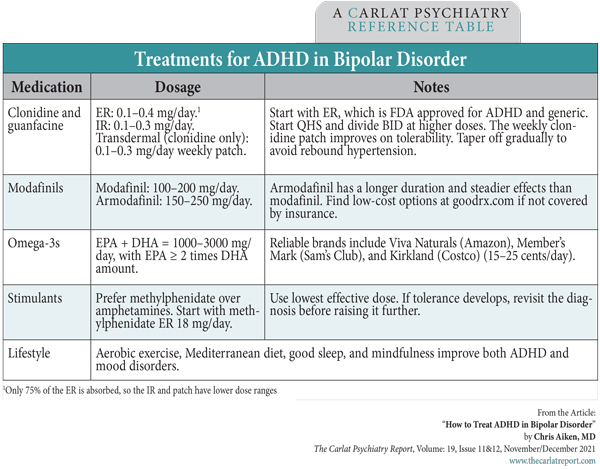

Table: Treatments for ADHD in Bipolar Disorder

Practical pearls for treating bipolar plus ADHD

I usually start with an alpha-agonist if the patient has insomnia, or the modafinils if they struggle more with depression and fatigue. Of the two alpha-agonists, guanfacine has more evidence to improve executive functioning, while clonidine has more studies in related comorbidities like self-harm, PTSD, and opioid and nicotine use disorders. Clonidine is also more sedating. Among the modafinils, most patients prefer armodafinil for its steadier plasma levels and longer duration of action.

The alpha-agonists take a few weeks to work in ADHD, while the modafinils have same-day effects much like the stimulants. With traditional stimulants, assessing response is tricky because their rewarding effects may bias the patient’s report. In my experience, the following signs point to a true ADHD response:

- Calming: Improvement in hyperactivity, impatience, and irritability

- Executive function: Better able to organize and prioritize complex tasks

- Sustained improvement

In contrast, patients without ADHD usually emphasize benefits in energy and motivation and may have “crashing fatigue” as the stimulant wears off at the end of the day. After a few months, tolerance tends to develop, prompting requests for higher and higher doses.

TCPR Verdict: About 10%–20% of patients with bipolar disorder have DSM-based ADHD. To treat this comorbidity, stabilize mood first. Alpha-agonists and the modafinils are good options to start with, while the stimulants may carry risks in bipolar disorder, particularly the amphetamines.