Probiotics in Psychiatry

The Carlat Psychiatry Report, Volume 19, Number 1, January 2021

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/tcprv19n1/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Alternative treatments | C-Reactive Protein | Complementary treatments | CRP | Depression | Depressive Disorder | Exercise | Inflammation | Mind-Gut Connection | Natural Medications | natural treatments | Nutrition | Obesity

Ted Dinan, MD, PhD

Ted Dinan, MD, PhD

Professor of psychiatry at University College Cork, Ireland. Dr. Dinan’s research focuses on depression, irritable bowel syndrome, and the influence of the gut microbiota on brain function. He has published over 500 scientific papers and numerous books, including 2019’s The Psychobiotic Revolution.

Dr. Dinan has disclosed that he has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

TCPR: What is the gut microbiome?

Dr. Dinan: It is the collection of microorganisms within the intestine. It functions like a separate organ and is about the same weight as an adult brain. Mainly it’s made up of bacteria, which is where our research has focused, but there are viruses and fungi in there as well. The traditional view was that these organisms are along for the ride—we feed them, and they don’t do us any harm. In the last 15 years we’ve realized that the relationship is more complicated and—when it goes well—symbiotic. We feed them, and they in turn produce chemicals that the brain and body require.

TCPR: How do these bacteria influence the brain?

Dr. Dinan: Much of the communication is through the vagus nerve, which sends signals from the brain to the gut and vice versa. In 2011 we showed that certain microbes can no longer communicate with the brain if the vagus nerve is cut in a mouse (Bravo JA et al, Proc Natl Acad Sci 2011;108(38):16050–16055). Microbes also produce molecules that are important to brain function. Tryptophan, a building block of serotonin, is synthesized by Bifidobacteria. Some species produce short-chain fatty acids that we cannot make on our own. Cytokine modulation is another possible route for this brain-gut communication. Cytokines are involved in inflammatory signaling, which has been linked to depression.

TCPR: What’s an example of how the microbiota influences behavior?

Dr. Dinan: Well, people with depression have a very different microbiota; it’s much less diverse than healthy controls. In our lab we transplanted the microbiota of depressed patients into rodents, and the rodents started to act “depressed.” This was a blinded study, and we didn’t see any changes in a control group where the transplant came from healthy subjects. And along with that depressive behavior, we saw changes in tryptophan metabolism and elevations of C-reactive protein, a marker of inflammation (Kelly JR et al, J Psychiatr Res 2016;82:109–118).

TCPR: Are other psychiatric disorders associated with altered microbiota?

Dr. Dinan: Depression is the most extensively studied. Researchers have also found alterations of the gut microbiota in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and autism, but this research is not as robust, and it’s not clear whether the alterations are due to differences in eating or other behaviors or whether they are actually playing a causative role in the illness. Recently researchers have found alterations in addictions, and there’s a new study where they transplanted microbiota from healthy subjects into patients with alcoholism and found that alcohol cravings were reduced significantly in 90% of the transplant subjects compared with 30% of the placebo subjects (Bajaj JS et al, Hepatology 2020; doi:10.1002/hep.31496. Epub ahead of print).

TCPR: Does the microbiota influence social behavior?

Dr. Dinan: It appears to. When mice are raised in a germ-free environment—so they have no microbiota—they are much less likely to interact with other mice. They also have abnormalities in serotonin transmission. We are about to publish a study showing microbiota alterations in social anxiety disorder.

TCPR: How does a person develop a poor microbiome?

Dr. Dinan: Our microbiotas initially develop at birth. If we come into this world through vaginal birth, our initial microbiota is largely determined by the Lactobacilli from the birth canal. With Cesarean section, the initial microbiota is radically different and is acquired from microbes on the skin of the doctor, the skin of the mother, and just from the general environment. This is relevant because C-section rates are increasing dramatically around the globe. After that, diet is the main determinant. A fast food diet is not going to produce a healthy microbiota. Medication is another big determinant, and it’s not just antibiotics. At least 75% of all the drugs that doctors prescribe impact the gut microbiota, and that figure is even higher for psychiatric medications. Aging is also relevant. The microbiota tends to become less diverse as we age, and frailty follows very rapidly from that.

TCPR: On that note, do antibiotics raise the risk of depression?

Dr. Dinan: If you look at meta-analyses of antibiotics, overall they tend to be associated with an increase in rates of depression. The problem with these studies is that infection increases the rate of depression and is potentially a confounding variable.

TCPR: What is the evidence that we can improve mental health by improving the gut microbiome?

Dr. Dinan: First, one of the limitations of this research is that it is relatively new and most of the studies are small (less than a hundred subjects). But there are several dozen placebo-controlled trials now, and here’s what they’ve found. Certain probiotics can reduce stress responses and may improve anxiety and depression. These studies were conducted in patients with major depressive disorder, patients with medical illnesses and comorbid depressive symptoms, and healthy subjects under stress. There is also a large placebo-controlled study where researchers started Lactobacillus rhamnosus in the second trimester of pregnancy and it lowered the rate of postpartum depression and anxiety with a large effect size (1.0–1.2); this was a secondary analysis, since they’d set out to look at eczema (Slykerman RF et al, EBioMedicine 2017;24:159–165). There are negative studies out there too—our group has published some of them—but on balance the studies in depression, anxiety, and stress lean positive. Most of them used probiotics, but some used prebiotics, live-culture yogurt, or fermented foods.

TCPR: What about other psychiatric disorders?

Dr. Dinan: The results are less consistent in other disorders. There are small studies in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and autism. Sleep is an area of growing interest. The microbiota has its own circadian rhythm, and sleep disorders are associated with poor microbiome health. We did a placebo-controlled study showing improvements in sleep with probiotics in university students, and a recent meta-analysis of 14 controlled studies found improvements in sleep quality with probiotics (Irwin C et al, Eur J Clin Nutr 2020;74(11):1536–1549).

TCPR: How can people improve their microbiota health?

Dr. Dinan: Diet is the most important way, and aerobic exercise also has a very positive benefit on the microbiota. The Mediterranean and Japanese-style diets are the best studied. I recommend that patients eat more fish, fruit, vegetables, whole grains, and fermented foods; limit red meat consumption to once a week; and reduce processed, fried, sugary, and fast foods. Fruits and vegetable contain over 1,000 identified polyphenols, like resveratrol from grapes and red wine and anthocyanidins from berries, and many of these polyphenols have profound effects both on the gut microbiota and the brain.

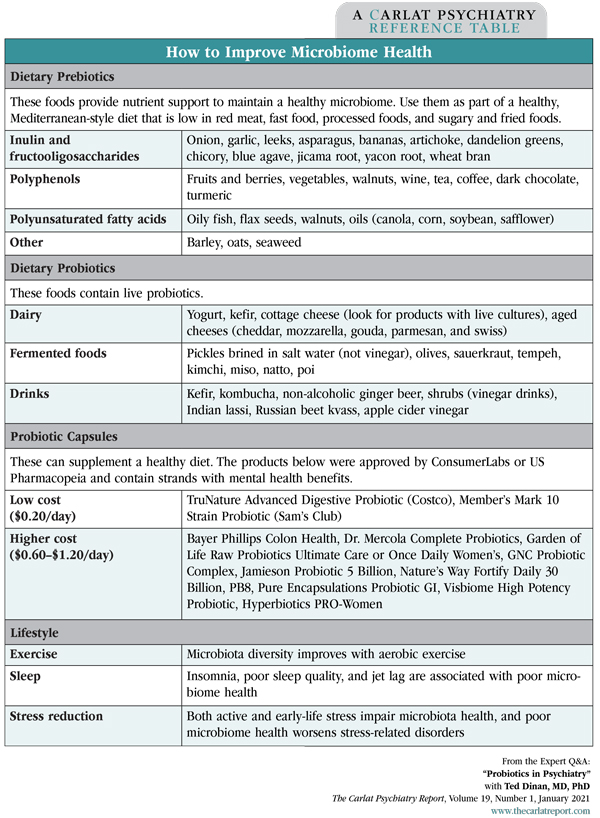

Table: How to Improve Microbiome Health

TCPR: You mentioned prebiotics. How are these different from probiotics?

Dr. Dinan: Prebiotics are fibers that promote the growth of good bacteria. The most widely studied prebiotic is inulin, which is found in a variety of vegetables: Jerusalem artichoke, onions, celery, and garlic. We also see modulations in the stress response—through reductions of morning cortisol levels—with prebiotics.

TCPR: And probiotics?

Dr. Dinan: Probiotics are the bacteria themselves, which we can take in capsule form. The FDA actually prefers the word “live biotherapeutics” because so many supplement companies have made outrageous health claims about probiotics. But in terms of educating our patients, we know that Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria are good for us. But I’m a big believer that the best source of most nutrients is in good food—not in a capsule. So eating yogurt with live cultures, drinking kefir and kombucha, consuming kimchi and other fermented foods—these are all extremely good sources of probiotic bacteria.

TCPR: Why do you prefer dietary change over probiotic capsules?

Dr. Dinan: A healthy diet does so much more than just change the microbiome. It’s important for vascular and metabolic health, and it has many effects on the brain. There’s polyphenols that offer neuroprotection; omega-3s that are the building blocks of neural cell membranes; and folate and other vitamins that are involved in neuropeptide production. Food is also the ideal delivery system, but if the patient can’t change their diet, then a capsule is the next best thing.

TCPR: Are there any risks with probiotics?

Dr. Dinan: You should avoid probiotics in people who are dramatically immunocompromised. Outside of that, I don’t see much of a risk as long as the product was appropriately produced. The only risk is that it may have no impact whatsoever.

TCPR: How would you guide a patient to choose a probiotic?

Dr. Dinan: Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli are the most widely studied genuses of bacteria for their anti-anxiety and anti-stress effects. I’d also look for a probiotic from a reputable company. Generally, the bigger companies are more likely to produce a high-quality product and not make outlandish claims that would attract the ire of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA).

TCPR: Which is better: a probiotic with a single strand of bacteria, or a combination of strands?

Dr. Dinan: We don’t have definitive studies on that, but a recent meta-analysis suggests that multiple probiotics—which we call polybiotics—are more effective than single strains in depression (Goh KK et al, Psychiatry Res 2019;282:112568).

TCPR: Do probiotics need to be refrigerated?

Dr. Dinan: Not necessarily. The bacteria in capsules are freeze dried—they are in a dormant state—so refrigeration probably doesn’t make a big difference as long as the capsules aren’t stored at an exceedingly high temperature. Bacteria are incredibly resilient. One thing that can kill them off, though, is acid, and some of these probiotics won’t make it through the acidity of the stomach.

TCPR: Researchers are also changing the microbiota through fecal transplant. Do you think we’ll ever see that approach used in clinical practice?

Dr. Dinan: Right now the only indication for fecal transplant is treating chronic C. difficile infection in elderly people. They have been used experimentally in psychiatry, for example in autism and alcoholism, but the procedure has risks—you could be transmitting a virus that wasn’t picked up in the original donor sample. My hope is that one day we’ll develop artificial feces that might have eight or nine probiotics in it. We just need to find out the key microbes for optimal health and artificially grow them.

TCPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Dinan.