Psychotherapy and Medication in Recurrent Depression

The Carlat Psychiatry Report, Volume 19, Number 6&7, June 2021

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/tcprv19n67/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Brief psychotherapy | Deprescribing | Depression | Depressive Disorder | Prevention | Psychotherapy | Therapy during medication appointment | Therapy with Med Management | Treatment-Resistant Depression

Giovanni Fava, MD

Giovanni Fava, MD

Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at the State University of New York at Buffalo. Editor-in-Chief of the journal Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics and author of over 500 scientific papers. His book, Discontinuing Antidepressant Medications, is due from Oxford University Press in 2021.

Dr. Fava has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

TCPR: When depression is recurrent, we usually continue the antidepressant indefinitely. Has that practice come under challenge?

Dr. Fava: Yes. Antidepressant drugs are certainly important during the depressive episode, but what we are starting to question is whether they are as effective in preventing relapse. A meta-analysis from 12 years ago found that antidepressants are not as effective in recurrent depression as they are in single episodes (Kaymaz N et al, J Clin Psychiatry 2008;69(9):1423–1436).

TCPR: But there are studies showing preventative effects, right?

Dr. Fava: There are studies where remitted patients were taken off antidepressants, or randomized to stay on them, and they seem to favor the medication. The problem with these studies is that they did not differentiate between withdrawal and relapse (Baldessarini RJ and Tondo L, Psychother Psychosom 2019;88(2):65–70). Withdrawal reactions are extremely common with SSRIs and SNRIs, and we have no way to know how many of the relapses in those trials were actually withdrawal and post-withdrawal syndromes.

TCPR: You’ve advocated for “sequential treatment” as an alternative to keeping these patients on antidepressants for the long term. Can you describe this approach?

Dr. Fava: Yes, it involves sequential use of antidepressants and psychotherapy. We first introduced sequential treatment in 1994 as a way to treat residual symptoms of depression. These are the low-grade depressive symptoms that patients suffer from after coming out of an episode, and they put the patient at risk for relapse. We start with an antidepressant. After 4–6 weeks we should have a good idea if that antidepressant is working, and if it is we’ll keep them on it for another few months. Improvement on antidepressants is usually steady and progressive for the first 3 months of treatment. After 3 months we reassess the patient, this time looking for residual symptoms. Then we taper the antidepressant and start psychotherapy to address the residual symptoms. These residual symptoms, by the way, are tightly related to the prodromal symptoms that brought the patient into a full episode in the first place.

TCPR: So the clinician needs to understand the prodromal symptoms that led up to the depression in order to prevent the next episode?

Dr. Fava: Right, and the best time to assess for that is not in the acute phase of the illness; it is when the patient has gotten better. We can then ask, “What was going on before the depression began?” And they’ll say, “Oh yeah, as a matter of fact, before becoming depressed I started avoiding social situations.”

TCPR: It sounds like this requires more than running a depression screen like the PHQ-9.

Dr. Fava: Yes, that’s totally inadequate. What we need to do is to interview the patient after a course of pharmacotherapy as if they were a new patient—starting from the very beginning and tracking all of the possible symptoms. We might say, “When I first saw you, you were off the road. I prescribed an antidepressant and now you are back on the road. However, if you drive the way you did before the depression, you will go off the road again sooner or later.” Then we start psychotherapy while tapering the antidepressant.

TCPR: Why wait? Why not just add psychotherapy from the start?

Dr. Fava: Because when we look at studies that combine the two, adding the therapy does very little to change the outcome. It’s with this intensive, two-stage approach that we see the difference, and we’ve recently confirmed that in a meta-analysis of 17 randomized controlled trials (Guidi J and Fava GA, JAMA Psychiatry 2021;78(3):261–269).

TCPR: What type of psychotherapy do you use in sequential treatment?

Dr. Fava: In the first studies we used CBT to address residual depression, which usually involves symptoms such as anxiety, irritability, avoidance, giving up easily, and interpersonal difficulties like friction in relationships and inhibited communication. Then we realized traditional CBT was not enough. Now there are three main models for preventing depression—well-being therapy (WBT), preventive cognitive therapy, and mindfulness-based CBT. These build from CBT and can be delivered in group or individual sessions.

TCPR: You helped develop well-being therapy (WBT). Tell us about what it is.

Dr. Fava: WBT is a manualized, short-term psychotherapeutic strategy that emphasizes self-observation, with the use of a structured diary, homework, and interaction between patient and therapist. It does not have to be intensive; in our studies we used 1 session every other week for a total of 8–10 sessions. To borrow a phrase from Jerome Frank, WBT is essentially guided self-therapy.

TCPR: What happens in the sessions?

Dr. Fava: One thing that sets WBT apart from many other therapies is that we don’t just look at what is wrong. We want patients to experience positive affect, not simply the absence of depression. This involves self-observation. We ask them to look for times that things are going well and record them in a diary. Patients with recurrent depression often lack what we call transfer of experiences. In other words, they do not pull from past successes, such as a time when they successfully coped with a problem that they are once again struggling with. For example, take a university student who has intense anxiety about a test. He does better than he expected on it, and over the next year he grows in his academic skills. But when exam time comes around again, he has the same intense anxiety as though he has learned nothing in the past year. So in WBT, we help patients become more aware of their strengths.

TCPR: And the diary of positive experiences helps them develop that awareness?

Dr. Fava: Yes, but that’s not the diary’s only purpose. It’s also the basis for identifying and overcoming obstacles (thoughts and behaviors) to well-being. At first the patient may say, “Well, my diary will be blank. I never have positive experiences.” That’s never true—they may feel bad 90% of the time, but there might still be 10% when they feel well. The problem is that these moments are fleeting, and we address that in the next session. When they bring in their diary, I will ask, “OK, so you felt good in that situation, but then you stopped feeling good; why?” And for the next assignment I’ll ask them to write down what kept those moments from continuing.

TCPR: What are some common responses?

Dr. Fava: Often it is unrealistic expectations or opportunities that are not pursued. For example, “I was able to solve a problem at work. I felt good. But then I thought about other things I’m not able to do and the moment stopped.” Then the therapist will make practical suggestions and problem-solve ways to keep those moments going.

TCPR: I often hear patients dismiss their success by focusing on their feelings, such as “Yes, I was able to get through that, but it was miserable. I felt anxious.” Does part of this work involve shifting their focus from emotions to functioning?

Dr. Fava: Yes. And it is not simply a matter of making the patient more aware cognitively. It is also a matter of behavioral activation; changing how they are living in some way. The aim is to build resistance to stress (ie, resilience, frustration tolerance, adaptability, and flexibility) and a unifying outlook that can consistently guide their actions toward their values and goals and—ultimately—a more meaningful life (Editor’s note: A WBT manual is available at www.well-being-therapy.com).

TCPR: Many patients are unable to engage in regular psychotherapy for various reasons. What can we do for them?

Dr. Fava: When I see a patient, I always write two prescriptions. One is the medication. Then, on a second pad, I will make some simple lifestyle suggestions and discuss the evidence supporting those ideas. Then I will say, “The medication will likely help you 50% if things go really well; the other 50% is up to you.” And I tell them, “This is more important than the medication.” Sometimes the patient comes back and they don’t feel sufficiently better, but they say, “Probably your medication worked, doc, but I didn’t do my 50%.”

TCPR: How do you choose that advice?

Dr. Fava: It has to be personalized, based on what is learned through the clinical interview. I generally write very simple things, like doing something outdoors because otherwise they will sit on the couch all day and stew in negative thoughts. I might recommend they pursue things that create optimal experiences for them.

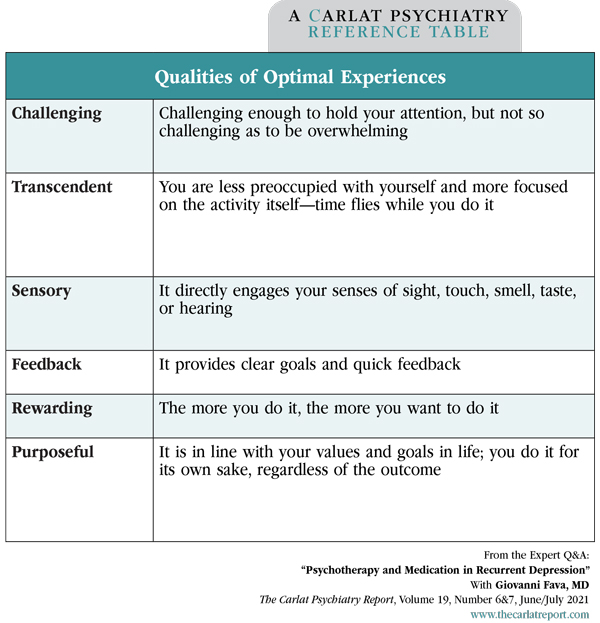

Table: Qualities of Optimal Experiences

TCPR: What are “optimal experiences”?

Dr. Fava: These are the things that they do well; that they enjoy and gain satisfaction from (see table at right). Some call it being “in flow” or “in the zone.” These experiences are characterized by the perception of high environmental challenges and environmental mastery, deep concentration, control of the situation, clear feedback on the course of activity, and intrinsic motivation. They might include activities like sports, school, or projects. What matters is that they are challenging enough to hold the patient’s attention and bring a sense of accomplishment, but not so challenging as to be overwhelming.

TCPR: Once you shift from the antidepressant to the psychotherapy, do you continue the antidepressant or taper it off?

Dr. Fava: That has to be a shared decision, but we strongly encourage patients to taper and discontinue their antidepressant. Tapering goes better when they have the support of a therapist. Otherwise it is very difficult.

TCPR: So even though they have residual symptoms, you would still consider tapering the antidepressant?

Dr. Fava: Yes, if there is at least partial remission and no depressed mood, because psychotherapy in the sequential model will take care of that. The results for this model are rather robust: It significantly decreases the likelihood of relapse compared to clinical management or treatment as usual even with long-term follow-up, such as 6 years (Guidi and Fava, 2021). There are randomized controlled studies that indicate sequential treatment is significantly better than treatment as usual, even when you taper and discontinue medications. No other approach does that.

TCPR: So why taper? Why not just keep them on the antidepressant?

Dr. Fava: Antidepressants were developed to treat severe episodes of depression, and this is still where we have the best evidence for their use. It is only as the drugs became more tolerable that we stretched their original indications to milder forms of mood disturbances and relapse prevention. However, if treatment is prolonged beyond 6 months, phenomena such as loss of clinical efficacy, episode acceleration, and switch into bipolar illness may ensue. There are also long-term side effects such as weight gain, gastric toxicity, and sexual dysfunction, as well as withdrawal symptoms if you try to discontinue them. Those hidden costs may outweigh their apparent gains in some patients, particularly when we lack good evidence of their maintenance effects.

TCPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Fava.

Related Podcast Episode

A Therapy to Prevent Depression with Giovanni Fava, MD

Antidepressants get people better from depression, but what keeps them better? In this episode, Dr. Giovanni Fava suggests we may need to stop trying to stamp-out pathology and start finding ways to enhance well-being as patients recover.

View full episode page with transcript.