Using Mental Health Apps

The Carlat Psychiatry Report, Volume 17, Number 10, October 2019

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/tcprv17n10/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Behavior therapy | Brief psychotherapy | Computers in Psychiatric Practice | Free Articles | Health Apps | Therapy during medication appointment | Therapy with Med Management

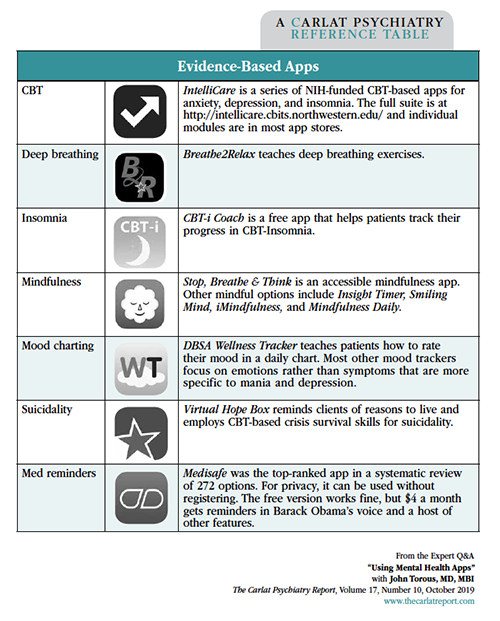

Director of the digital psychiatry division, Department of Psychiatry at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA Dr. Torous has disclosed that he has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity. TCPR: Computer-assisted therapies have been around for decades. What makes mental health apps different? TCPR: How do patients get these? Table: Evidence-Based Apps TCPR: How does a prescription app work, exactly? TCPR: What kind of evidence does it have? TCPR: What else is in the pipeline? TCPR: Is the game fun? TCPR: There are thousands more health apps that are not FDA approved. How do we navigate that sea? In addition, you must make sure the app ties into something that matters to the patient. The patient must be motivated to use the app. TCPR: What do we need to know to evaluate clinical trials of apps? TCPR: It’s surprising that screen time itself can be therapeutic. Can you give an example? program. They created a placebo version of the app that had the same visual experience, the same feel, and the same narrator, but contained no discussion of mindfulness—in other words, they took out the active ingredient. They gave the real and the fake app to 91 healthy college students for 6 weeks and tested various cognitive outcomes that are associated with mindfulness practice. In the end, the digital placebo worked just as well (Noone C & Hogan MJ, BMC Psychol 2018;6(1):13). TCPR: What are some apps that have good ease of use? TCPR: How do you introduce apps to patients? TCPR: It sounds like the way we use the app in therapy is more important than the app itself. TCPR: For those of us who are new to digital therapeutics, what’s a good way to try it out? TCPR: What’s a good target for daily steps with psychiatric patients? TCPR: Some patients are using apps to monitor their sleep. Can we rely on the data from these apps? TCPR: When would you use an app that tracks medication adherence? TCPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Torous.

John Torous, MD, MBI

John Torous, MD, MBI

Dr. Torous: Computers have been used to support psychotherapy in many forms—email, video conferencing, texting, and online or desktop programs. Mental health apps take this to another level because they work through a device that most people keep with them 24/7: their smartphone. One of the problems with computer therapy programs was that patients didn’t stick with them. Apps have the potential to be more engaging.

Dr. Torous: Anyone can download these programs from the app store on their smartphone. There are apps that remind patients to take their medication, or that connect them to peer support networks or directly to their provider through telepsychiatry. There are apps that guide patients through behavioral psychotherapies, using audio/video narration or interactive programs. There are even video game apps with therapeutic benefits. Patients are starting to use these health apps, and they may not be telling you. That can be a problem because most of the apps that are available are poorly designed and lack research support. Some give bad advice—like telling people with bipolar disorder to drink alcohol to sleep. On the other hand, those that have good studies behind them are often not available to the public. Some of the better-studied apps are coming out as prescription-only products that are approved by the FDA as “digital therapeutics.”

Dr. Torous: Right now there’s just one that’s FDA approved in psychiatry, reSET Connect by Pear Therapeutics, which is for addictions. The app is available for anyone to download, but to actually use it, patients need a prescription code, which they get when their physician enrolls them (www.resetconnect.com). The app has 61 CBT-based educational modules which patients are supposed to complete 3–4 times a week. The doctor then monitors the progress and enters the patient’s urine screen results on a separate dashboard. Patients get rewards, including gift cards, for sobriety. So it’s an app, but it’s really an interactive, therapeutic program that uses well-known behavioral techniques.

Dr. Torous: FDA requirements aren’t as rigorous for apps as they are for medications because the FDA views these devices as low risk. In reSET’s case, approval was based on a 3-month randomized controlled trial that compared reSET to usual care in 399 patients with alcohol, cocaine, marijuana, or stimulant use disorders. Abstinence rates were about double with the reSET app (40% vs 18%). There’s also reSET-O, approved for opioid use disorders. That one had a 3-month, unblinded, randomized controlled trial that was partially positive. Unlike with other substances, the program didn’t improve abstinence from opioids, but it did help patients stay in treatment longer (82% vs 62%). Interestingly, both trials used a desktop computer version of reSET, even though it was approved as an app.

Dr. Torous: Some of the CBT-insomnia apps are seeking FDA approval. There’s also a video game for ADHD in the works called “Project Evo.” The game requires children to multitask, such as steering a boat down a river while tapping on fish that pop up. There’s also an element of impulse control—players have to avoid tapping on certain-colored fish or birds. The game adapts to the player’s skill in real time—it gets harder or easier—which keeps it from getting too frustrating or boring (Yerys BE et al, J Autism Dev Disord 2019:49(4):1727–1737).

Dr. Torous: I would guess so. Adherence rates were very high. Children were supposed to play it for 30 minutes each day, but there was some concern that it could get addictive, so it shuts off for the day after 45 minutes of play.

Dr. Torous: There are three steps to consider: privacy, evidence, and ease of use. Here are some basic things to look for.

Dr. Torous: One thing that’s different from medication trials is the digital placebo. This is the idea that interacting with a digital device may have a therapeutic effect of its own, regardless of the app’s content. This has implications for study design: What type of placebo are we going to use? Some type of active control is necessary, and a lot of studies of apps used only a wait-list control. We did a review of depression apps and found that their effect size went down from medium to small when they went from a wait list control to an active control like journaling or using an informational app (Firth J et al, World Psychiatry 2017;16:287–298).

Dr. Torous: One intriguing example is a randomized controlled trial of the Headspace app, which is a popular mindfulness

Dr. Torous: IntelliCare is a family of CBT-based apps that has a nice interface. The idea behind these apps is that no one wants to watch PowerPoint-style CBT slides on their phones, which is what was done in the early versions of computer-based therapy. Instead, IntelliCare breaks the CBT skills into micro-doses that can be learned in one- to 20-minute exercises (see Evidence-Based Apps table on page 4 for additional examples).

Dr. Torous: The first thing to consider is how the app can augment the therapeutic alliance. Apps don’t work on their own, and you’re going to get a lot more efficacy when you use them inside the context of a therapeutic alliance. You want the patient to understand that you are still there providing support. The technology is not running the show—it’s a tool, and we must set expectations and boundaries around how we’re going to use that tool. If the app is tracking rating scales or medication adherence, will you be looking at the data remotely or just during sessions, and how will you respond to the data?

Dr. Torous: Exactly.

Dr. Torous: Step counters are a good place to start. These apps are built into most phones, and physical activity, which is what they measure, is relevant to most psychiatric disorders. You could start by looking at the patient’s steps and saying, “Let’s set a target of being just a little bit more physically active and see if it improves your mood.” Or you could phrase it as an experiment: “For the next week I want you to aim for this amount of steps a day. Then we’ll talk about days that you were more and less active, compare that to your mood, and make a plan.”

Dr. Torous: Ten thousand a day is always thrown around as this kind of magical number. I work a lot with patients with psychosis and the idea of 10,000 steps can be discouraging. So it’s worth taking whatever the patient’s current baseline is and saying, “Hey, let’s try to increase it by 500 steps a day.”

Dr. Torous: Watches and wristbands can collect various types of sleep data based on your movements at night. There are also sensors that sit by the bed and estimate the stage of sleep from breathing patterns, like ResMed’s S+ app. All these tools have flaws, but what they are best at telling us about is the duration of sleep, which can be a useful measure as it impacts almost every disorder we treat. They haven’t yet replaced an EEG. It’s very hard to measure REM vs non-REM sleep despite what companies claim. Another measure that’s useful is medication adherence. There are apps that can track that and provide pop-up dose reminders.

Dr. Torous: The key thing is to consider how you’re going to use the data in practice. Do you have a plan to encourage adherence when you get the information? You don’t want to track for the sake of tracking. Finally, you need an end point. You and the patient must decide what the goal is, when you’ve reached it, and when you are going to stop using the app.