How to Interview the Older Patient

The Carlat Geriatric Psychiatry Report, Volume 1, Number 1&2, January 2022

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/cgprv1n12/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | PDF of Issue

Topics: Free Articles

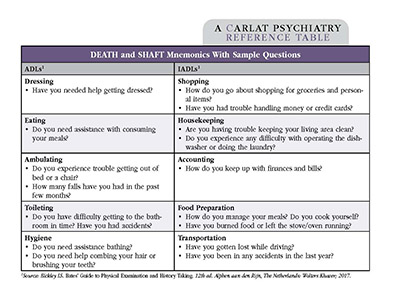

Rehan Aziz, MD. Inpatient geriatric psychiatry, Hackensack-Meridian Health, Perth Amboy, NJ. Dr. Aziz has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity. The expanding population of older adults has created a need for all clinicians to participate in their care. Interviewing techniques require adaptation in older adults, such as accounting for hearing or vision impairment and speaking slowly and clearly. This article will cover additional factors to consider when evaluating older patients. Functional assessment Appraising a patient’s functional status is critical. It’s done by asking about activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). IADLs are advanced skills, the first activities impacted by dementia. I recommend asking about them in the presence of a caregiver because patients may minimize their own deficits. See the table below for the unfortunate mnemonics DEATH and SHAFT along with sample questions to assess ADLs and IADLs. Table: Death and SHAFT Mnemonics With Sample Questions Click to view as full-size PDF. Mental status assessment Evaluation of mental status is similar to younger patients, but involves a few additional observations, which we detail below. Appearance Patients who experience depression or apathy might neglect hygiene. Those with cognitive disorders might be dressed inappropriately, such as wearing several layers on a warm day. Appearance can also provide a clue regarding the adequacy of the patient’s supports. Overwhelmed caregivers may have less time or energy to help a compromised patient. Psychomotor activity Older adults with depression, dementia, or altered mental status may have slowed movements. Patients with advanced dementia might appear disengaged from the interview. Patients with moderate dementia may pace. Patients with anxiety might fidget or wring their hands. Affect Older adults may demonstrate reduced emotions even in the absence of mental illness—in other words, a constricted affect doesn’t mean a patient is depressed. Depressed elders might present as withdrawn, irritable, weary, or apathetic. Paranoia, delusions, hallucinations Hearing or vision deficits can sometimes trigger hallucinations (fixable by correcting the deficits). Patients with Parkinson’s disease or dementia with Lewy bodies often experience complex visual hallucinations of people, animals, or shadows. Second-person auditory hallucinations are common in older adults with dementia. Severely depressed older patients may have auditory hallucinations that condemn them or encourage self-destructive behavior. Elders with moderate dementia often suffer from delusions. They can take various forms, such as delusions of infidelity or paranoia. Delusions may be triggered by short-term memory loss (eg, misplacing household items, then accusing a family member of theft). Delusional depression is more prevalent in older patients than in middle-aged adults (Blazer DG, FOCUS Spring 2004;11(2):224–235). The most common delusions are somatic or feature negative content, eg, “I’m losing my mind” (Gournellis R et al, Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001;16(11):1085–1091). Cognition A cognitive evaluation should be part of every initial assessment and then administered periodically. The most commonly used in-office standardized scales are the proprietary Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). Scales in the public domain include the Saint Louis University Mental Status exam (SLUMS) and the Mini-Cog (www.mini-cog.com). The single best assessment is the clock-drawing test: Ask the patient to draw the numbers on the face of a clock with the hands pointing to a specific time (often 10 minutes past 11 o’clock). Safety assessment Suicidal thoughts I start by asking every patient if they have thought that life is not worth living. Keep in mind that older adults may have thoughts about death and dying even if they are not suicidal, which is starkly different from younger individuals. If a patient has had suicidal thoughts, I ask how they would attempt suicide and whether they have the means to do so. Contrary to popular belief, most older patients are not offended by these questions. Intervention is necessary when a patient has seriously considered suicide and has the tools available to carry it out, such as firearms (Blazer, 2004). Because men drive suicide rates in the older adult population, pay close attention to ensure protective factors are in place for these patients. Driving Older adults are at higher risk for motor vehicle accidents (Cicchino JB, Accid Anal Prev 2015;83:67–73) due to decreased reaction times, impaired vision and hearing, and difficulty managing complex road situations. If I suspect cognitive impairment, I usually interview a family member. I ask whether the patient has gotten lost driving in familiar neighborhoods or whether they have missed traffic signs in the past few months. I also ask about recent tickets. I may perform a Trail Making Test Part B in the office, as there is good evidence that it correlates with driving ability. If I suspect a patient is unsafe driving, I request a driving evaluation or a retest. In the case of dangerous driving, clinicians may be obligated to alert the DMV. Wandering Wandering becomes an issue in moderate and severe dementia. Patients may become disoriented and unable to retrace their steps home. In some instances, patients wander outside in cold weather or onto highways. If a patient or caregiver reports concern about wandering, I suggest a few interventions. The patient can wear a medical ID bracelet or carry an item with embedded GPS tracking, such as a necklace, bracelet, or phone. I also recommend installing deadbolts, doorway alarms, or even cameras, and alerting neighbors and the local police of a patient’s wandering risk. Elder abuse Elder abuse can take many forms: physical, financial, sexual, abandonment, and neglect. Clinicians are mandated reporters of suspected abuse. Generally, I will interview the patient alone about how they feel at home, or how they feel with their family members or caregivers. I ask how they are managing financially. I review the patient’s advance directives and pay attention to who has permission to communicate with the patient’s clinicians. I observe weight loss, the patient’s hygiene, and whether the patient has bruises or cuts (keeping in mind that older adults may bruise from blood thinners or medical illnesses). Depending on the circumstances, I may call the local adult protective services agency. Many local, state, and national social service agencies can also help with emotional, legal, and financial abuse. If I suspect the patient is in immediate danger, I call 911 or the local police immediately. Carlat Verdict: Older adults require an expanded assessment, taking into account functional capacity, social support, cognition, and safety.

For both ADLs and IADLs, I determine whether patients are independent, require assistance, or are fully dependent on others. To assess the presence of caregiver support, I ask patients, “During the past four weeks, was someone available to assist you if you wanted help?”