Assessing and Treating Catatonia

The Carlat Hospital Psychiatry Report, Volume 2, Number 3&4, March 2022

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/chprv2n3-4/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Amantadine | Ativan Challenge Test | Benzodiazepines | Bush-Francis Scale | Catatonia | lorazepam taper | mood disorders | neuroleptic malignant syndrome | retarded vs excited catatonia | Schizophrenia

Stephan Heckers, MD

Stephan Heckers, MD

William P. and Henry B. Test Professor Chair, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Psychiatrist-in-Chief, Vanderbilt Psychiatric Hospital. Nashville, TN.

Dr. Heckers has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

CHPR: Welcome, Dr. Heckers. You recently published a review of the management of catatonia (Heckers S and Walther S, JAMA Psychiatry 2021;78(5):560–561). What is catatonia and how do you diagnose it?

Dr. Heckers: Catatonia is a psychomotor syndrome. Some patients cannot move or respond normally. Patients often stare blankly, remain motionless for long periods, and don’t talk or respond to questions. These presentations are typical of the akinetic form of catatonia, which is the most common. This form is sometimes referred to as retarded, inhibited, or stuporous catatonia, or as the Kahlbaum type of catatonia (Editor’s note: Karl Ludwig Kahlbaum was the first to describe catatonia in 1868).

CHPR: Are there other subtypes of catatonia?

Dr. Heckers: Yes, there’s also an excited, hyperkinetic subtype of catatonia, where patients are hyperactive and restless. The third subtype is malignant catatonia, which looks very similar to neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS). It can be life-threatening, but fortunately it’s very rare.

CHPR: How do you distinguish excited catatonia from the agitation of psychosis or mania?

Dr. Heckers: They can appear similar, but hyperactive catatonic patients typically engage in odd, purposeless, disorganized behaviors.

CHPR: To make sure we don’t miss the diagnosis, is it helpful to use a rating instrument?

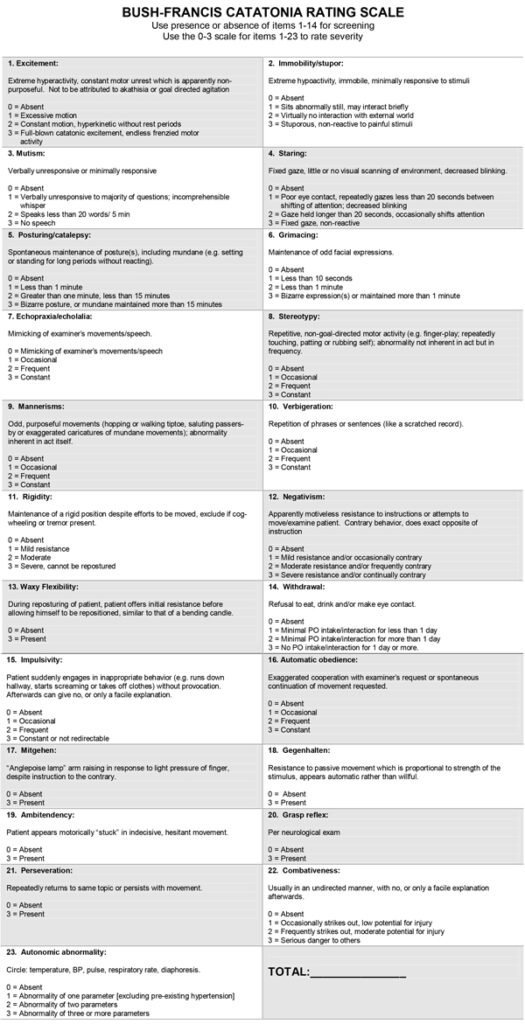

Dr. Heckers: Yes. We use the Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (Bush G et al, Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996;93(2):129–136). In fact, we use it so frequently that it’s now part of our electronic medical record. It measures the degree of immobility and mutism, as well as other features of catatonia, like grimacing, posturing, odd or stereotyped behaviors, hyperactivity, and waxy flexibility (Editor’s note: See the Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale below). We also use the Bush-Francis scale to monitor patients’ response to treatment.

CHPR: What are the most common underlying causes of catatonia?

Dr. Heckers: Catatonia is most common in mood disorders. But it also occurs in psychotic disorders, neurodevelopmental disorders, and various medical conditions. The excited form of catatonia is more typical of a patient with bipolar disorder than schizophrenia, but catatonia presentations generally appear similar, regardless of the underlying diagnosis.

CHPR: But one difference is that patients with underlying schizophrenia are less likely to respond promptly to benzodiazepines, compared to patients with underlying mood disorders, right?

Dr. Heckers: Most patients with catatonia respond to benzodiazepines, even patients with schizophrenia. More than two-thirds of all patients respond promptly even after a single administration, so benzodiazepines are the treatment of choice even if the patient has a diagnosis of schizophrenia. But patients with schizophrenia, particularly disorganized schizophrenia, often need an antipsychotic to fully recover.

CHPR: Do you worry that antipsychotic-induced extrapyramidal symptoms might worsen the catatonic symptoms or mask any improvement?

Dr. Heckers: Yes. We usually stop the antipsychotic and treat the patient with just a benzodiazepine, but around 20% of patients with catatonia also have a psychotic disorder that will not get better without adding an antipsychotic. So, we begin with a benzodiazepine and, if the patient is getting better but still has significant psychosis in addition to the catatonia, then we add an antipsychotic.

CHPR: I’ve seen that many psychiatrists are hesitant to use antipsychotics for patients experiencing catatonia.

Dr. Heckers: I understand that concern. Antipsychotics can lead to NMS and muddy the diagnosis: Does a patient have NMS or a severe form of catatonia? Also, antipsychotic-induced extrapyramidal symptoms can exacerbate a catatonic patient’s muscle rigidity and reduced movement. But these concerns miss the fact that some psychotic symptoms in catatonic patients—disorganized thought, for example—will not get better without an antipsychotic. We start with a low dose and monitor closely for any new onset or worsening of muscle rigidity.

CHPR: Are patients in catatonic states at greater risk of developing NMS than other patients taking antipsychotic medications?

Dr. Heckers: Yes. Some patients with catatonia can have extremely elevated creatine kinase values, sometimes in the hundreds or thousands. These are typically patients with prominent psychomotor presentations, who posture and are hyperactive. They might have frank muscle damage because they are so hyperactive, and they are the ones most likely to develop severe NMS if you initiate an antipsychotic.

CHPR: And how do we distinguish NMS from malignant catatonia?

Dr. Heckers: Both can present with changes in vital signs (increased heart rate, blood pressure, and body temperature) and high creatine kinase levels. In NMS you’re more likely to see lead-pipe rigidity (Editor’s note: See CHPR, Jan/Feb/Mar 2021 for more on NMS). The patient’s medication history aids the diagnosis since patients with NMS will have been taking antipsychotic medications. Also, patients with catatonia are more likely to display waxy flexibility, where you can move a patient’s limbs to a new position and they stay in that position.

CHPR: Should we preferentially use any specific antipsychotic medications in catatonia?

Dr. Heckers: We try to avoid the high-potency first-generation antipsychotics, so we use second-generation or third-generation partial agonists like aripiprazole. But few studies have compared medications for catatonia, so there isn’t compelling evidence that one is better or safer than the other.

CHPR: Please walk us through your treatment steps for catatonia.

Dr. Heckers: Most cases of catatonia get diagnosed in an emergency setting. In fact, catatonia is one of the more common reasons why a person presents to a psychiatrist in an emergency room. We treat with lorazepam (Ativan) 2 mg IM or IV, and patients typically respond very well. The excited form of catatonia often gets misinterpreted as agitation or mania, but when you realize that the patient is in a hyperactive state of catatonia—for example, demonstrating undirected, nonpurposeful motor activity—and treat with lorazepam, they respond quickly. Oral lorazepam is not as effective, and patients are often not able or willing to take PO medication.

CHPR: How quickly do you see a response to IM or IV lorazepam?

Dr. Heckers: Typically in five to 10 minutes—it’s the fastest response that we have in clinical psychiatry, akin to stopping a status epilepticus. I have seen patients with waxy flexibility, completely rigid, have a complete resolution with 2 mg of IV lorazepam and become capable of interacting normally.

CHPR: Why do you choose lorazepam vs another benzodiazepine?

Dr. Heckers: IM or IV lorazepam has a fast onset of action, within a few minutes. Case reports have described successful treatment with other benzodiazepines, like midazolam and clonazepam, but most studies of benzodiazepines for catatonia have used lorazepam.

CHPR: What do you do if the patient does not respond to lorazepam?

Dr. Heckers: If they don’t improve within half an hour, we add another 2 mg of lorazepam. And if they still don’t respond, we add an additional 2 mg 30 minutes later. We call this the Ativan challenge test. Most people respond to 6 mg of lorazepam, but we sometimes need to reach high doses—12, 16, even 20 mg—and might need to treat for two to three days before seeing a response.

CHPR: Are there any risks to this much lorazepam?

Dr. Heckers: We might encounter problems with the patient’s therapeutic window, which refers to the amount of lorazepam that will resolve the catatonia versus cause excessive sedation. If the therapeutic window is narrow, patients will fall asleep before we have a chance to see whether the medication is effective. We don’t worry about the concerns that come up with phenobarbital and other barbiturates, such as suppression of breathing.

CHPR: What’s your next step if the benzodiazepine doesn’t work?

Dr. Heckers: When benzodiazepines are ineffective, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is our next option. If ECT is not available, alternative treatment options include glutamate antagonists, like amantadine 100–600 mg daily or memantine 10–20 mg daily, and valproic acid 500–1500 mg daily (Beach S et al, Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2017;48:1–19). If those still don’t work, then we must ask ourselves whether we’re missing something.

CHPR: Do you change your management if the catatonia is mild vs severe, or akinetic vs hyperkinetic?

Dr. Heckers: Less severe forms of catatonia usually improve with lower doses of benzodiazepines compared to more severe forms, but our management otherwise remains basically the same. This remains true for akinetic vs hyperkinetic forms of catatonia. They both respond to benzodiazepines, but hyperkinetic manifestations may require higher doses.

CHPR: And what’s on your differential?

Dr. Heckers: In addition to mood and psychotic disorders, we consider delirium, various systemic and toxic conditions, and neurologic illnesses like strokes or brain-occupying lesions. Patients with autoimmune encephalitis—particularly anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis—can present with catatonia, usually before they develop more severe forms of encephalopathy.

CHPR: What tests would you want to obtain in your workup?

Dr. Heckers: Depending on the patient’s clinical presentation, we might want to obtain brain imaging. We’ll also want a toxicology screening and routine blood tests like a comprehensive metabolic screening and CBC. A lumbar puncture will be necessary if encephalitis is a possibility.

CHPR: For catatonic patients who don’t respond promptly, are there medical sequelae we should watch for?

Dr. Heckers: Most cases with catatonia are not so severe that patients would develop a deep venous thrombosis, a pulmonary embolism, pressure ulcers, or severe dehydration, but these do happen. Therefore, we hold that a patient who is not moving needs to be treated like a patient who is unable to move for neurological reasons to prevent the consequences of prolonged immobility.

CHPR: And once the patient’s catatonic state has resolved, how long do you maintain the lorazepam?

Dr. Heckers: If it’s an acute episode of catatonia that responds well to a benzodiazepine, we stop the benzodiazepine at the end of the hospitalization. Sometimes we discharge the patient with a taper over the course of a month, during which we slowly take them off the benzodiazepine. But some patients will need to be maintained for several months on a slow taper of lorazepam. We might discharge the patient on 2 or 3 mg, typically broken down into one or two doses over the day, and then very slowly taper it off over several months.

CHPR: How do you know which patients will need a taper?

Dr. Heckers: We’ll do what’s referred to as the negative challenge test: We take the patient off the benzodiazepine while they’re still on the inpatient unit. If we see a rapid resurgence of the catatonic presentation, that indicates that the patient will need maintenance or a very slow outpatient taper.

CHPR: So, some patients basically need to be on maintenance treatment to avoid this relapse?

Dr. Heckers: I’m taking care of patients who need long-term maintenance with benzodiazepines. Some need maintenance ECT because when we stop the treatment, the patient will have a relapse of catatonia.

CHPR: What do we know about the pathophysiology of catatonia?

Dr. Heckers: Very little. It’s striking because catatonia is one of the most treatment-responsive conditions in psychiatry. There are two theories. The first focuses on the motor circuit in the brain and makes the case that catatonia is an abnormality of motor planning. The second centers on the affective charge and the heightened anxiety often seen in patients with catatonia, akin to a severe panic attack, with the idea being that people are frozen out of fear. This theory proposes that the limbic system, the orbitofrontal cortex, and the amygdala are driving a person into a severe form of anxiety, which in turn produces the catatonia. From a pathophysiologic perspective, these are two very different mechanisms and very different brain regions. Neuroimaging has not provided a definitive answer. We have animal models for some features of catatonia, but they have not provided new clues for interventions yet. The pathophysiology is remarkably unclear.

CHPR: You made a point in your paper about mild forms of catatonia often going unrecognized. Can you say a little more about this?

Dr. Heckers: A mild form of catatonia is negativism, which Herman Melville succinctly captured in the phrase “I would prefer not to.” It is willful avolition, not quite the same as the lack of will and motivation that we recognize as a negative symptom of schizophrenia. Many psychiatrists reserve the diagnosis of catatonia for the complete inability to engage, but that is a misconception.

CHPR: Any final thoughts?

Dr. Heckers: I’ll end by saying that I find Eugen Bleuler’s concept of ambivalence to be very relevant to catatonia. Among Bleuler’s “four A’s” of schizophrenia, Autism, Affect, and Association made perfect sense, but the fourth—Ambivalence—eluded me for many years, until I realized that Bleuler was referring to catatonia. He gives an example in one of his books: Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias (Madison, CT: International Universities Press; 1950). He goes on his morning rounds and sits down at a patient’s bed and addresses her, saying “I am Dr. Bleuler. How are you doing?” The patient says nothing and doesn’t move. But when he leaves the room, the patient says “Dr. Bleuler, I want to talk with you.” He describes it as an example of ambivalence: When you engage, the patient doesn’t respond, but when you turn away they give you a sign, either saying or doing something to indicate that they’re willing to engage. This ambivalence, I’ve realized more and more, can indicate a subtle form of catatonia.

CHPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Heckers.

Table: “Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale”