Borderline Personality Disorder in the ED

The Carlat Hospital Psychiatry Report, Volume 2, Number 1&2, January 2022

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/chprv2n1-2/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Borderline Personality Disorder | Countertransference | Emergency Department | emotion dysregulation | Good Psychiatric Management | interpersonal stressors | Personality Disorders | Suicidality | Working With Families

Victor Hong, MD

Victor Hong, MD

Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Dr. Hong has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

CHPR: What are some common issues that you encounter with patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) in the psychiatric emergency department (ED)?

Dr. Hong: First, we should remember that individuals with BPD are prevalent in every psychiatric setting, but especially the ED. About 10%–15% of all psychiatric ED patients have BPD, and these patients often present repeatedly (Pascual JC et al, Psychiatr Serv 2007;58(9):1199–1204). That can be very frustrating for clinicians, who might have the attitude of “Wait, didn’t I just see you? You’re here again? You made another suicide attempt?” Adding to the frustration, there’s the issue of chronic suicidality and self-harm behaviors. We worry about patients killing themselves if we discharge them. There’s typically a lot of drama surrounding individuals with BPD. And the frenetic nature of EDs adds to the challenge of working with these patients, since they’re interpersonally hypersensitive and easily triggered emotionally.

CHPR: So how can we best work with these patients in EDs?

Dr. Hong: It helps to think of patients with BPD as a special population who require a distinct, organized approach. Good Psychiatric Management principles, based on APA guidelines, are particularly useful in the emergency setting (Hong V, Harv Rev Psychiatry 2016;24(5):357–366). Do these principles solve all the problems? Definitely not, but if clinicians and staff have a better understanding about why the patients behave the way they do and how to proactively mitigate that behavior, everyone benefits.

CHPR: Can you review the fundamental points of Good Psychiatric Management?

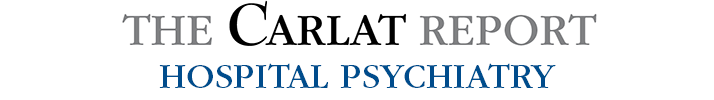

Dr. Hong: There are several evidence-based treatments for BPD, the most well known being dialectical behavior therapy. There’s also mentalization-based therapy, transference-focused psychotherapy, and other evidence-based treatments. But these modalities are time intensive and require lengthy training, and few practitioners are adequately trained in them. They’re difficult to implement in acute care settings like inpatient units or EDs. John Gunderson and his team at McLean Hospital developed the Good Psychiatric Management modality (Gunderson J et al, Curr Opin Psychol 2018;21:127–131). It’s intended to be a generalist model that can be easily taught in an eight-hour training. There are several principles that are relevant for the ED (Editor’s note: For more information, see the “Good Psychiatric Management Fundamentals” table).

Table: Good Psychiatric Management Fundamentals

CHPR: Which are the main principles?

Dr. Hong: The most essential principle is that the core attribute of individuals with BPD is interpersonal hypersensitivity, and most crises come out of interpersonal stressors. For example, the patient has an argument or there’s a breakup or a perceived breakup, and in response the individual self-harms or threatens or attempts suicide, ending up in the ED. To help these patients, we need to get straight to the heart of the issue and explore their interpersonal stressors.

CHPR: What’s another important principle?

Dr. Hong: A second key principle is that you want to provide psychoeducation, including a review of evidence-based treatments. The acute care setting provides an opportunity to review the diagnosis if it is already established, and to bring up the possibility of BPD if it is suspected. You can review the DSM criteria together and see if the patient thinks the diagnosis fits. Another way, if the patient is frustrated that medications don’t seem to be helpful, is to ask, “Might something else be going on? Has anyone ever mentioned BPD?” And then a third key principle is to quickly work to develop rapport with a patient with BPD.

CHPR: How do you do that?

Dr. Hong: One effective way is to be more active and engaged than you might otherwise be. There was a study that took patients with BPD and control subjects and told them to let their minds wander. It showed that the minds of patients with BPD, compared to controls, tended to wander toward negative thoughts (Kanske P et al, Psychiatry Res 2016;242:302–310). So, if you take a neutral approach to a patient and sit back in our chair and don’t say much, patients with BPD will often interpret that behavior negatively and think, “This person is being dismissive and doesn’t care about me.” But if you sit forward and make it very clear that you’re interested and engaged, asking about their lives and their relationships, that approach helps develop rapport and trust.

CHPR: So, it helps to be highly engaged in our interviewing. And back to your comment about patients’ self-harming behavior: How do you distinguish between chronic self-harming behaviors and real suicidality?

Dr. Hong: This is one of the most stressful aspects of managing patients with BPD. Yes, these patients do carry an elevated risk of suicide compared to the general population. But too often we use that chronic risk to guide us in our clinical decision making, and that can lead to unnecessary hospitalizations. It helps to look at the patient’s acute risks. For patients with BPD, to hammer home the point, the triggers are typically interpersonal stressors, like real or perceived abandonment. There are patients who will attempt suicide after they lose a therapist or after their significant other threatens a breakup. So, we need to be attuned to those specific risk factors for suicidality in patients with BPD.

CHPR: Anything else we should be mindful of?

Dr. Hong: No matter how many times the patient has threatened suicide, it’s important to provide validation and hope, and maintain and exhibit a genuine concern about their safety. Even though you might be seeing a patient for suicidality for, say, the 20th time, from the patient’s perspective their suicidality is very fresh. And if they’re coming to the ED or inpatient unit as a last line of defense and they’re met with a hostile or dismissive attitude, that can increase their suicide risk. So, no matter how frustrated you might be with the patient, you need to remember that they’re in crisis. Additionally, patients with BPD often need us to interpret what they’re saying. So, if somebody says “I’m suicidal” or “I want to die,” or cuts themselves or takes pills, they may be communicating: “I’m lonely. I feel abandoned. I’m upset and I don’t know what to do about it.”

CHPR: It must be very reassuring for a patient to hear someone put their feelings into words. By helping patients develop greater self-awareness, does that help reduce their visits to the psych ED?

Dr. Hong: Over time, if patients can gain a sense of what triggers emotional reactions, understand how they can self-soothe, and remember that whatever they are feeling will likely pass, they’ll have a better chance of avoiding an ED visit. This is an important point because for a lot of patients with BPD, recurrent visits to the psych ED and hospitalizations can be harmful. Some patients develop a dependence on the hospital system to the point that they run to the ED whenever they’re in distress, and this can handicap them in developing self-soothing techniques.

CHPR: Is there anything else we can do to minimize recurrent visits to psych EDs?

Dr. Hong: For somebody who is coming to the ED time after time, it’s important to collaborate with everyone involved in the patient’s care—the outpatient therapist, the outpatient psychiatrist, and the patient. Everyone should understand when the patient should call the therapist or psychiatrist, when they should go to the ED, and when they should use self-regulation and self-soothing techniques. And if they do come to the ED, everyone should be on the same page regarding the expectations of an ED visit, the criteria for hospitalization, and the goals for discharge if the patient is hospitalized.

CHPR: In these collaborative meetings, do you include family members?

Dr. Hong: Yes, whenever possible. These families are often desperate for help. Sometimes they don’t have a good understanding of BPD; sometimes they’re terrified that they’re going to lose their loved one to suicide. So, it is crucial to engage families in the care. It’s also a good liability risk reducer to involve families in the care, but this isn’t always easy. BPD often runs in families, so family members themselves might have BPD or other cluster B traits, which obviously can complicate family meetings. There are also a lot of cases, given BPD’s ties to trauma, where family members have engaged in overt abuse of the patient. But as much as possible, I try to have the families engaged.

CHPR: Do you provide any psychoeducation to family members?

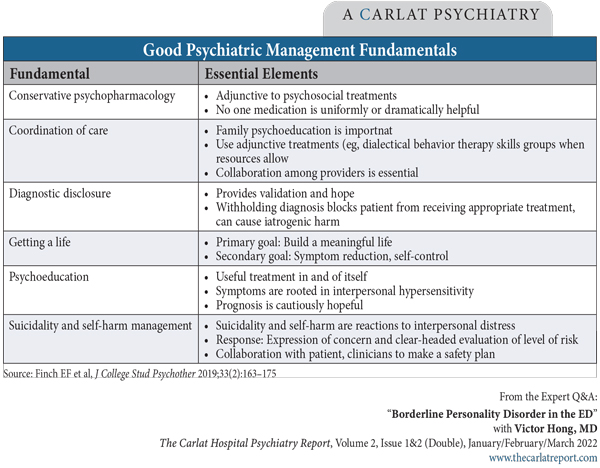

Dr. Hong: We hand out educational material for families in the ED, which I think is very helpful. These materials include tips like being aligned as a family unit to avoid splitting (Editor’s note: See “Tips for Family Members” table). And if families need more assistance, there’s a program called Family Connections offered through the National Education Alliance for BPD, and they provide education and support groups for families (Editor’s note: For more information, see www.borderlinepersonalitydisorder.org/family-connections).

Table: Tips for Family Members

CHPR: You mentioned liability concerns. Are there any other thoughts you have about reducing liability risk?

Dr. Hong: In terms of reducing liability, an important point is to appropriately manage countertransference reactions. These reactions are often born out of a sense that the patient is intentionally trying to cause problems. We hear terms like, “They’re being manipulative.” Patients may seem like they’re being overly dramatic to get attention, but often the truth is that they don’t know how to express their emotions in a more regulated way. I highly value the process of venting with a trusted colleague. These patients create stressful situations, and venting can help you have a cooler head when you interact with them.

CHPR: Those are good tips.

Dr. Hong: And going back to the question of liability, you don’t want the first time you’re meeting a family to be in the ICU after a patient has taken an overdose. You will want to have met them before that to say, “I’m concerned about your family member. There is a real risk of suicide in this illness. We’re going to do the best we can. These are the evidence-based practices.” If somebody does die by suicide and you have that connection with the family, then an honest, frank appraisal of the situation can reduce liability. And the last thing I’ll say about reducing liability involves conversations with supervisors and colleagues. Many of us don’t do these consultations enough, especially if you’re a more experienced clinician. But we can all use a second opinion, no matter how many times we’ve dealt with a patient with BPD or how many years of experience we have. We all have blind spots. That is a very important liability risk reducer.

CHPR: If you get to the point where you need a medication, do you have any tips for psychopharmacology management?

Dr. Hong: There are no FDA-approved medications for BPD or any other personality disorder, so everything we’re using is off label. Try to focus on specific symptom clusters, like psychosis or agitation. Low-dose antipsychotics win out for most symptom clusters, like mood dysregulation, paranoia, and dissociation. For patients with comorbid anxiety disorders or a concurrent major depressive episode, SSRIs rise to the forefront. SSRIs sometimes need to be pushed to higher-than-usual doses, whereas for antipsychotics, high doses have not been shown to help more—but of course, they can lead to more side effects (Black DW et al, Am J Psychiatry 2014;171(11):1174–1182).

CHPR: What about benzodiazepines?

Dr. Hong: It’s important to be careful with benzodiazepines. They work well, almost too well, and for a patient who is often distressed and can be easily calmed by a benzodiazepine, that’s a setup for dependence. So, if you use a benzodiazepine, you must be strict about it being very short term.

CHPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Hong.