Combination Treatment for Schizophrenia

The Carlat Hospital Psychiatry Report, Volume 1, Number 1, January 2021

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/chprv1n1/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Adjunct treatment | Antidepressant | Antipsychotic | Benzodiazepine | CATIE | Combination treatment | Free Articles | Mood stabilizer | Outcomes | Psychopharmacology | Schizoaffective disorder | Schizophrenia | Substance Use Disorder

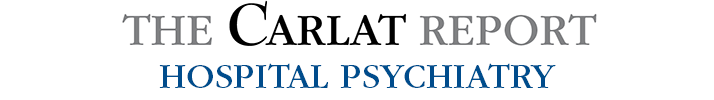

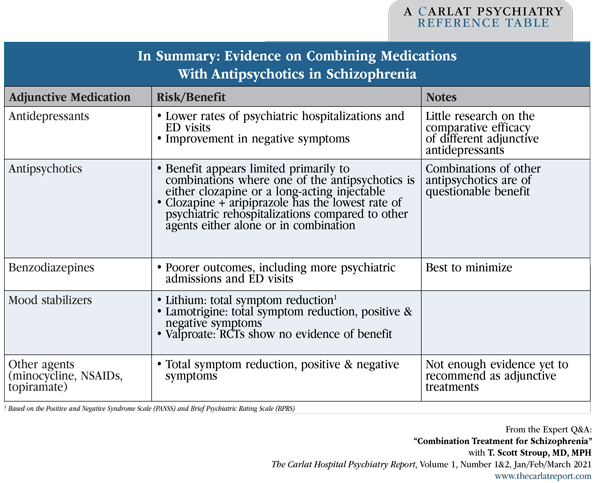

Professor of Psychiatry, Columbia University, NY. Dr. Stroup has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity. CHPR: You recently published a study on the use of adjunctive medications in patients with schizophrenia (Stroup TS et al, JAMA Psychiatry 2019;76(5):508–515). Your findings were provocative as you found that adjunctive medications often help improve patients’ outcomes, yet many clinicians avoid polypharmacy because of concern that patients will experience more side effects without a clear benefit. CHPR: Is this why you decided to do your study? CHPR: What was your study’s methodology? CHPR: Which group benefited the most? Table: In Summary: Evidence on Combining Medications With Antipsychotics in Schizophrenia CHPR: How did you know that the results weren’t confounded by indication? A patient on an antidepressant might have had negative symptoms that would have been less likely to lead to a psychiatric admission, while another patient might have received a benzodiazepine for agitation and this was the reason for the psychiatric admission. CHPR: What is propensity score weighting? CHPR: Have any other studies shown benefits to adjunctive antidepressants? CHPR: Were any specific antidepressants more helpful than others? CHPR: What does the literature tell us about which types of patients with schizophrenia benefit from antidepressants? CHPR: Based on your findings with benzodiazepines, would you caution against using them as adjunctive agents? CHPR: Are there any studies on combinations of two antipsychotic medications? CHPR: So combining two antipsychotics was more effective? That contradicts received wisdom. CHPR: In that Finnish study, were there any antipsychotic combinations that were especially effective? Table: Top 10 Medication Combinations That Reduced Rehospitalization CHPR: What about mood stabilizers? CHPR: What’s known about other agents? CHPR: Are there any subgroups of patients with schizophrenia that respond less well when adjunctive agents are added to the antipsychotic medication? CHPR: Did your research lead you to any recommendations about long-term, maintenance treatment? CHPR: A statement you made in one of your papers struck me. You said, “Because breakthroughs do not appear imminent, we must find ways to use current treatments better.” CHPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Stroup.

T. Scott Stroup, MD, MPH

T. Scott Stroup, MD, MPH

Dr. Stroup: That was my starting point too. I have always encouraged parsimonious use of psychotropic medications beyond antipsychotics in people diagnosed with schizophrenia. There has been little high-quality research into this question. Many of the studies have been small, and results have generally been mixed or inconclusive. Direct information about the comparative effectiveness of different adjunctive treatments is really lacking.

Dr. Stroup: Yes. We know that adjunctive medications are widely used for patients with schizophrenia. More than half of patients with schizophrenia receive an antidepressant over the course of a year. Many also take mood stabilizers, benzodiazepines, or additional antipsychotics. We wanted to see if there were any benefits from adjunctive medications and how they compared.

Dr. Stroup: We took 10 years of national Medicaid data and identified 323,500 patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. We focused specifically on patients who were already taking a single antipsychotic, and then we explored how they responded when a second medication was added. These adjunctive medications were from the following categories: another antipsychotic, an antidepressant, a mood stabilizer, or a benzodiazepine. Out of the initial 323,500 patients, there were 81,921 patients who met these criteria of having been prescribed a second medication.

Dr. Stroup: We found that people who started antidepressants did better in terms of lower rates of psychiatric hospitalizations and psychiatric emergency department visits. Benzodiazepines, on the other hand, were associated with higher rates of psychiatric hospitalizations and emergency department visits (Editor’s note: See “In Summary” table below).

Dr. Stroup: Great question. In an observational data set, people are not randomized, so it’s hard to make causal inferences. With the advice of my excellent and experienced colleagues, Mark Olfson, Tobias Gerhard, and others, we used propensity score weighting to make sure people in the different medication groups were as similar as possible.

Dr. Stroup: It is a statistical technique that controls for biases in observational studies. It adjusts for differences in pre-treatment demographic and clinical variables. In a claims database like Medicaid, of course, clinical information is somewhat limited, so there’s still the possibility of unmeasured confounding.

Dr. Stroup: There have been a few. A study using a large patient registry in Sweden found that antidepressant use was associated with reduced mortality when compared to patients on antipsychotic monotherapy (Tiihonen J et al, Am J Psychiatry 2016;173(6):600–606).

Dr. Stroup: We did not look at differences among antidepressants in our study. However, three years ago a systematic overview of 14 meta-analyses examined 42 pharmacologic co-treatments. They found that SNRI and SSRI antidepressants were both more effective than antipsychotic monotherapy for negative symptoms. SNRIs were also beneficial for total symptom reduction. None of the antidepressants seemed to help positive symptoms (Correll CU et al, JAMA Psychiatry 2017;74(7):675–684).

Dr. Stroup: The most consistent evidence is that antidepressants are helpful for negative symptoms. Some studies have also reported that antidepressants are helpful for other symptoms besides negative symptoms. It would be reasonable to speculate that they are helpful for depressed mood or anxiety, but our study couldn’t address this.

Dr. Stroup: I’m skeptical of benzodiazepines in this population. In addition to higher rates of psychiatric hospitalizations and ED visits, benzodiazepines have been associated with higher mortality rates (Tiihonen J et al, Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012;69(5):476–483). There is also concern about accidents and the potential for dependence. I recommend minimizing benzodiazepine use in people with schizophrenia.

Dr. Stroup: A recent registry-based study from Finland worked with a database of 62,250 patients over 20 years and found about a 10% lower risk of psychiatric rehospitalization among patients treated with antipsychotic polypharmacy as opposed to monotherapy with a single antipsychotic (Tiihonen J et al, JAMA Psychiatry 2019;76(5):499–507).

Dr. Stroup: Indeed it does. It may be time to modify the current treatment guidelines that discourage combination therapy.

Dr. Stroup: Yes, the superstar combination was clozapine and aripiprazole, which was associated with a 14% reduced risk of hospitalization compared with clozapine alone, which was the most effective of all the monotherapies studied. The top 10 treatments all included either clozapine or a long-acting injectable medication, so my interpretation is that those are the key ingredients for effective antipsychotic combinations (Editor’s note: See table below). On the other hand, quetiapine was the poorest monotherapy performer in this study, and adding any antipsychotic to quetiapine was better than quetiapine alone.

Dr. Stroup: The Correll study I mentioned earlier found benefits when lithium or lamotrigine were added as adjunctive agents. Lithium was helpful for total symptom reduction, while lamotrigine was helpful for positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and total psychopathology. While open studies have reported that adjunctive valproate helps with specific symptoms such as aggression, randomized controlled trials have not found convincing evidence that valproate augmentation is beneficial.

Dr. Stroup: The Correll study also saw some benefits for other adjunctive agents, including minocycline, topiramate, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs). It’s important to keep in mind that some of this information came from small studies or a single study.

Dr. Stroup: When we did the CATIE schizophrenia trial, we found that among people who use illicit substances, none of the antipsychotic medications worked particularly well (Swartz MS et al, Schizophr Res 2008;100(1–3):39–52). In the current study, patients without substance use disorders (SUDs) benefited from the addition of antidepressants more than those with SUDs. We also found that the subgroup of people with SUDs had a much higher rate of psychiatric hospitalizations compared to people without SUDs. This was more evidence that this is a challenging clinical problem.

Dr. Stroup: Our follow-up was for 1 year. Although that may not seem long term for people diagnosed with schizophrenia, the findings have made me less skeptical about using additional medications, whether for acute or for maintenance treatment. I no longer say, “Avoid using additional medications” like I might have at one time.

Dr. Stroup: And that’s what I’ve focused on: conducting comparative effectiveness studies in clinical trials and more recently using secondary data. The research community can learn from practice, ie, “practice-based evidence.” Lately I have been using Medicaid data to look at geographic variations in the way medications are prescribed. We are finding that for patients with schizophrenia, adjunctive antidepressants are used consistently across the country. This finding that antidepressant use is consistent across the US makes me think even more that there must be something to learn from this practice.