Decisional Capacity

The Carlat Hospital Psychiatry Report, Volume 1, Number 3&4, April 2021

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/chprv1n3-4/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Aid to capacity evaluation (ACE) | Capacity | Collaborative care | Decisional Capacity | Dispositional capacity | Free Articles | Medical incapacity hold | Surrogate decision-maker

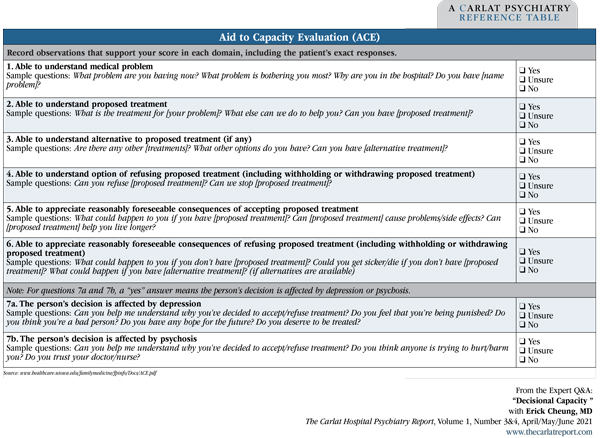

Associate Medical Director, UCLA Resnick Neuropsychiatric Hospital. Chief Quality Officer, Department of Psychiatry, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA. Dr. Cheung has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity. CHPR: Can you start by telling us what criteria you use to assess capacity? CHPR: Can you say a bit more about these domains, perhaps with a case example? Four Domains of Decisional Capacity Can the patient: CHPR: We often see patients like this. What do you do next? CHPR: Some of the most challenging cases involve depressed patients who refuse lifesaving interventions. How do you approach capacity evaluations with these patients? CHPR: And how do you approach capacity evaluations for patients who have severe mental illnesses or who are intellectually disabled? CHPR: That’s a good point. A patient might seem to lack capacity simply because they are not able to understand the medical terminology—or for that matter, the language, if the patient is not a native English speaker. We need to be sure to use a medical interpreter in cases where there might be a language barrier. CHPR: Do you recommend any formal capacity assessment tools to make sure you’re using the proper wording? Table: Aid to Capacity Evaluation (ACE) CHPR: For us to determine a patient has capacity, would they need to score a “Yes” on every question on the ACE? CHPR: So let’s assume you determine the patient lacks capacity for a treatment. What’s your next step? CHPR: What if you cannot identify either an advance directive or a surrogate decision-maker? CHPR: How do you handle patients who need non-emergent treatment, don’t have capacity to consent, and don’t have a surrogate to make medical decisions on their behalf? CHPR: Another tricky situation is how to handle patients who lack capacity to make medical decisions yet insist on leaving the hospital against medical advice. CHPR: So how do you handle this dilemma? CHPR: None of those options sound good. CHPR: What are the criteria? CHPR: Hospitals around the country might benefit from following your model and instituting similar policies. How can they obtain more information? CHPR: Are there liability concerns we should keep in mind as we do capacity evaluations? Suppose a patient refuses a treatment, then has a bad outcome, and a family member claims the patient didn’t have the capacity to refuse treatment. CHPR: Especially if you were to have a second physician document that they’re in agreement with the lack of capacity. CHPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Cheung.

Erick Cheung, MD

Erick Cheung, MD

Dr. Cheung: We generally look for evidence of capacity in four domains. These have become the standard criteria for assessing capacity, based on Dr. Paul Appelbaum’s work from many years ago (Appelbaum PS and Grisso T, N Engl J Med 1988;319(25):1635–1638). The domains are: 1) ability to communicate a choice; 2) ability to understand the relevant information; 3) ability to appreciate a situation and its consequences; and 4) ability to reason rationally.

Dr. Cheung: Let’s say you are consulted to evaluate an adult male with a history of bipolar disorder who is admitted to the medical unit for kidney failure. The internal medicine team tells you that his condition is severe and he needs urgent dialysis. Each time staff try to talk to him about his condition or a procedure, he curses, orders them to leave him alone, and says that he is “fine.” So you go to the bedside and begin the capacity evaluation. You first assess his understanding by asking if he knows why he is in the hospital and how the doctors are trying to help him, but all you get from him is, “I don’t care” and, “Maybe it’s something about my kidneys.” He can’t elaborate any further, nor can he say what the treatment would be.

Dr. Cheung: You then explore if he understands the consequences of his decision by asking if he understands what will happen if he refuses treatment. He answers, “I don’t need dialysis; I’m fine.” You explain that his kidneys are severely impaired and that, without dialysis, he might die. He responds in a hostile manner, “Fine, let me die.” You check his reasoning capacity by asking, “Why are you saying we should let you die?” Patients who are lucid and have capacity can give you reasons for their refusals of interventions, perhaps related to their values, preferences, and perceived quality of life. This patient answers, “I’m not going to die; I’m fine!” He adds, “I don’t want dialysis or any treatment. I just want to go home!” At this point—even though he has expressed a choice—he has shown significant impairments in the three other domains (understanding, consequences, reasoning), enough to declare that he does not have capacity to make this medical decision. Often, psychiatrists pair capacity evaluations with psychiatric evaluations, so you spend some additional time trying to understand the patient’s bipolar disorder and whether he is currently experiencing a mood episode, and how this may be complicating his ability to make decisions about his treatment.

Dr. Cheung: I struggle, too, with those cases because they’re among the most complicated ones we see. I start with the presumption that all patients have the capacity to make decisions about their medical care until proven otherwise. So, it’s incumbent upon us to try to understand whether the depression is unduly influencing the patient’s ability to comprehend the medical treatment and the consequences of their decision. And is the patient’s decision-making process and choice consistent over time? We want to make sure to treat the depression as fully as possible to reduce the impact on the patient’s decision-making. We also gather information from other sources. For example, do people who are close to the patient think the patient’s decisions are unduly influenced by depression? Do they have information about the patient’s prior expressed wishes about medical care? Also, remember to ask about any advance directive that lays out a person’s preference for what kinds of treatment they will and won’t accept.

Dr. Cheung: Intellectual disability and severe mental illnesses do not preclude somebody from making decisions unless they’ve been deemed unable to make medical decisions by a court of law and/or have an assigned guardian or conservator who makes medical decisions for them. But in most cases, these patients can still engage in decision-making about their medical care. It’s important, though, to avoid medical jargon and adjust the information that you give them to a level that they can understand, but that is still accurate and complete. For example, a patient might understand information more easily if it’s presented in a visual form rather than written or spoken. It is often helpful to engage family or caregivers in the conversation, as these individuals may assist with conveying the information more clearly for the patient.

Dr. Cheung: That’s right.

Dr. Cheung: Standardized capacity assessment tools are helpful, although they can sometimes make the interview seem a little rigid. If clinicians would like to use a semi-structured evaluation tool, there are several that are free and available. For example, the Aid to Capacity Evaluation (ACE) lists straightforward questions that help to make an initial determination about a patient’s capacity. The ACE is useful when a patient does not appear to have capacity because it will clearly show you the domains where they are lacking.

Dr. Cheung: Not necessarily. The threshold for sufficient capacity changes according to the seriousness of the proposed intervention. For a low-risk intervention—say, a chest x-ray or a flu shot—we don’t expect the same level of capacity as for a high-risk or invasive intervention like surgery. In the latter case, a patient should be clearly able to answer all the questions in the capacity assessment. We also would want to be sure that patients understand everything that is involved as follow-ups to high-risk procedures. A good example is patients undergoing capacity evaluations for liver or other transplants. Transplants impart a lifetime of treatment that a patient needs to clearly understand before they consent to the procedure.

Dr. Cheung: The next step is to try to restore capacity to the patient such that they have the autonomy to be able to make decisions for themselves again. For example, this could be treating the underlying medical condition to resolve a patient’s delirium. That would be the best-case scenario. If the time frame doesn’t allow for that, or the impairment is more protracted, then you’d look for other types of information that can help guide your decision-making. This includes advance directives and surrogate decision-makers. There can be a specifically legally authorized decision-maker, like a durable power of attorney for healthcare decisions or a court-appointed decision-maker. If that legally authorized representative doesn’t exist, the next step would be to look for a spouse, an adult next of kin, a parent or sibling, and on down the family chain.

Dr. Cheung: That’s where things get challenging. When you are faced with an urgent medical decision, you can resort to the emergency treatment laws in your state to decide whether the needed intervention falls under an emergency treatment exception.

Dr. Cheung: Great question. State laws tend to be unhelpful in resolving this problem, so it’s best to have a predetermined hospital policy that lays out a process to determine the best decision that can be made on behalf of a patient who lacks capacity and who does not have a surrogate. In some places, this is handled by an “unrepresented patient committee” that takes on the role of surrogate decision-maker (Editor’s note: See QA with Dr. Saba Syed for more details about unrepresented patient committees).

Dr. Cheung: This is a pervasive and challenging situation. Medicine or surgical teams often call the psychiatric consult-liaison service to request that a psychiatric hold be placed on a confused, delirious patient who is trying to leave the hospital. Patients who don’t have underlying psychiatric illnesses don’t meet the psychiatric hold criteria, but psychiatry consult-liaison teams often place the psychiatric holds because there is no other way to keep these patients safe from the serious risks of leaving the hospital.

Dr. Cheung: Clinicians typically do one of three things. The first option is to place an inappropriate involuntary psychiatric hold, as I just mentioned. The second option is to let the patient leave—an ethically problematic decision. Imagine the confused patient walking out of the hospital and then having some bad outcome. That’s everyone’s greatest fear, and you run a risk of medical malpractice for negligence in care. And the third option is to order the patient to be held, but there is no legal justification upholding this option, and clinicians and staff risk being charged for false imprisonment.

Dr. Cheung: Right. At our hospital, we have established a “medical incapacity hold” policy that addresses a patient’s lack of dispositional capacity—which refers to a patient’s capacity for self-management post-discharge. Instead of having the individual clinician bear the risk of detaining a patient, we put it on the institution, and we have spelled out the parameters in our policy, such as the criteria for detainment.

Dr. Cheung: Our policy permits an adult patient to be kept from leaving the medical center if they: 1) are making efforts to leave that place them at grave risk for serious harm, disability, or death; 2) do not have the capacity to understand the risks of leaving and declining care; and 3) do not meet legal criteria for an involuntary psychiatric hold. If the patient meets all these criteria, and lesser restrictive measures have failed, then the treating clinician can order a medical incapacity hold that will prevent the patient from leaving the medical center.

Dr. Cheung: We cover our policy in detail in our paper, “The Medical Incapacity Hold: A Policy on the Involuntary Medical Hospitalization of Patients Who Lack Decisional Capacity” (Cheung EH et al, Psychosomatics 2018;59(2):169–176).

Dr. Cheung: Liability concerns are not typically a significant concern for me in this work. People have a right to make bad decisions, decisions that other people wouldn’t make. If you follow a careful assessment and documentation of capacity at multiple time points, this is good medical and legally sound practice. When you add other sources of information—like from a family member, somebody who knows the patient’s pattern of decision-making, or anyone else who is involved in the patient’s care—and they corroborate the patient’s decision, your risk is usually minimal.

Dr. Cheung: Yes, a second opinion is generally a good idea when there’s ambiguity about the case. Second opinions are not required by any legal standard, but psychiatrists or ethicists often get called when the cases are ambiguous and there’s a question related to either a mental health condition or some other ethically challenging situation that psychiatrists are more attuned to be able to tease apart. And I want to emphasize the importance of reassessment at different time intervals. Once you see that consistency, you have much greater certainty that the patient is making an informed choice.![]() To learn more, listen to our podcast, “Decisional Capacity.” Search for “Carlat” on your podcast store.

To learn more, listen to our podcast, “Decisional Capacity.” Search for “Carlat” on your podcast store.