Deliberate Foreign Body Ingestion

The Carlat Hospital Psychiatry Report, Volume 1, Number 1, January 2021

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/chprv1n1/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Borderline Personality Disorder | Deliberate foreign body ingestion | DFBI | Free Articles | Gastroenterology | Malingering | Management | Obsessive compulsive disorder/OCD | Personality Disorders | Pica | Psychosis | Self-injury | Swallowing

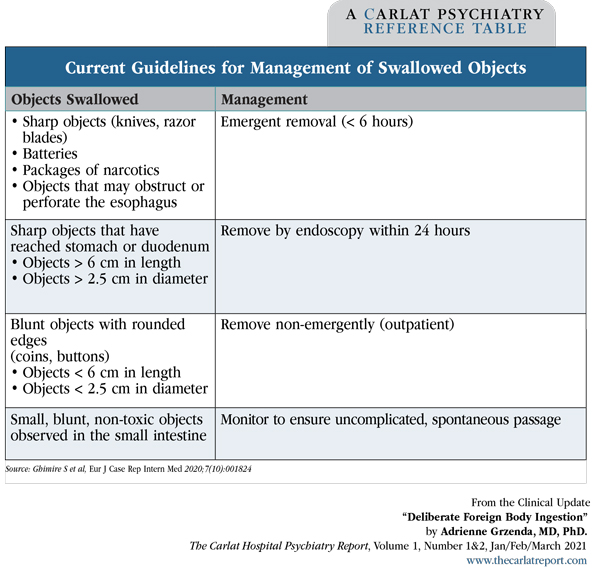

Adrienne Grzenda, MD, PhD. Clinical Assistant Professor of Psychiatry & Biobehavioral Sciences, UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine and UCLA-Olive View Medical Center. Dr. Grzenda has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity. During morning rounds at your inpatient unit, you are informed by staff that your patient M, a 32-year-old woman with bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder, has swallowed a small pencil. This is her fourth swallowing episode since her admission to the unit 2 weeks ago. Even though you had restricted her access to sharp objects, she has managed to take them from other patients or pick them up off the floor. You are not sure whether to call a GI consult because you are wary of encouraging her behavior with the secondary gain of medical attention. You do a literature search on deliberate foreign body ingestion to help come up with a plan for M. Patients with repeated deliberate foreign body ingestion (DFBI) are among the most challenging we see. DFBI is costly and resource intensive, in part because of these patients’ extremely high rate of repeated swallowing attempts: Over 80% of DFBI presentations occur in patients with prior ingestions (Palta R et al, Gastrointest Endosc 2009;69(3 Pt 1):426–433). A retrospective analysis of 305 cases of DFBI found they involved only 33 patients and generated over $2 million in costs in a single year (Huang BL et al, Clin Gastroenterol and Hepatol 2010;8(11):941–946). What do these patients swallow? Why do patients swallow foreign objects? Management of DFBI Current guidelines recommend emergent removal (< 6 hours) of sharp objects (eg, knives, razor blades), batteries, packages of narcotics, or any objects that may result in the obstruction or perforation of the esophagus. For sharp objects that have already progressed to the stomach or duodenum or objects greater than 6 cm in length and/or greater than 2.5 cm in diameter, removal by endoscopy is recommended within 24 hours. Blunt objects with rounded edges (eg, coins, buttons), smaller than 2.5 cm in diameter, and/or smaller than 6 cm in length can be removed non-emergently in an outpatient clinic. Small, blunt, non-toxic objects observed in the small intestine can be monitored to ensure uncomplicated, spontaneous passage. Once objects reach the stomach, most will pass within 4–6 days. Seek surgical consultation if the object fails to progress after 72 hours or the patient develops symptoms of perforation, obstruction, or peritonitis. (Editor’s note: See table below.) Table: Current Guidelines for Management of Swallowed Objects DFBI patients require a multidisciplinary approach involving surgery, medicine, and psychiatry. Frustration with the patient may lead to animosity between services due to the perception that psychiatry is not “doing enough” to prevent repeated behaviors. Consultant-liaison providers can help the treatment team or caregivers to: 1. recognize countertransference forces at play, 2. provide education on the limited efficacy of pharmacologic and behavioral treatments, 3. set limits to lessen reinforcement of maladaptive behaviors, and 4. foster realistic expectations regarding recurrence. At present, we know little about the long-term prognosis for patients with recurrent DFBI. General management of DFBI for inpatient and institutionalized settings focuses on reducing the frequency and potential lethality of ingestions. We can minimize swallowing incidents by monitoring patients closely and minimizing their access to swallowable items (eg, utensils, pens, combs, toothbrushes). Specific management principles vary depending on the subtype. For DFBI due to malingering, minimize the secondary gain: Transfers for hospital treatment should be kept as brief as possible. When personality disorders are the underlying cause, target the impulsivity with the use of mood stabilizers, naltrexone, or clonidine (Gitlin DF et al, Psychosomatics 2007;48(2):162–166). Dialectal behavior therapy and cognitive behavior therapy can also help. Like for other self-injurious behaviors in patients with BPD, inpatient admissions after a swallowing incident can be counterproductive, fostering an exacerbation of symptoms (Poynter BA et al, Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2011;33(5):518–524). Unless there are additional indications (eg, psychotic symptoms, suicidal ideation), swallowing incidents alone do not justify psychiatric admission. For DFBI rooted in delusional beliefs or driven by command hallucinations, treat the underlying psychosis. SSRIs—fluoxetine in particular—appear effective for DFBI due to pica/OCD (Upadhyaya SK and Sharma A, Indian J Psychol Med 2012;34(3):276–278). You ascertain that the pencil M swallowed was less than 6 cm and was not sharpened; your GI consultant (also frustrated with the patient after several endoscopies) recommends a wait-and-see approach with serial x-rays to assess whether the object progresses through the GI tract. You ask M why she swallowed the pencil, and she says she was frustrated by all the restrictions placed on her access to unit objects. You work with her to create a clear behavior plan allowing for gradual reintroduction of objects with every 24 hours of non-swallowing behavior. After 1 week, M has complied with the plan and has regained her privileges. CHPR Verdict: Patients with recurrent DFBI are among the most difficult to treat. Identify the subtype to choose the most effective treatment, minimize psychiatric admissions as these can be counterproductive, and collaborate closely with a gastroenterologist.

Pens, toothbrushes, and batteries are among the most commonly ingested items. Some patients experience no symptoms, while others present with dysphagia, drooling, emesis, gastrointestinal bleeding, pharyngeal or abdominal pain, and respiratory distress. Fortunately, 80%–90% of swallowed foreign bodies pass spontaneously through the gastrointestinal tract. Another 10%–20% will require intervention via endoscopy, and less than 1% require surgery (Dray X and Cattan P, Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2013;27(5):679–689). Complications, including perforation, impaction, and bleeding, depend on the type, size, and location of the ingested object. Foreign bodies with corrosive properties, such as button batteries, can be particularly harmful as they can result in necrosis and fistulas.

In most cases, DFBI patients are not suicidal: They have no greater risk of lifetime suicidal thoughts or actions compared to patients with other types of non-suicidal self-injurious behaviors (Hom MA et al, J Nerv Ment Dis 2018;206(8):582–588). What, then, explains this vexing swallowing behavior? Individuals with DFBI fall into four diagnostic categories: malingering, borderline personality disorder (BPD), psychosis, and pica.

Surgical management of DFBI depends on the characteristics of the swallowed object, time since ingestion, current location in the GI tract, and presence of complications. Non-contrast CT is better than x-ray in evaluating for ingested objects; if the ingested object is radiolucent, x-rays are of no use.