Intranasal Esketamine: New Hope for Suicidal Patients?

The Carlat Hospital Psychiatry Report, Volume 1, Number 1, January 2021

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/chprv1n1/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Depression | Esketamine | Fast-acting | Free Articles | Intra-nasal | Ketamine | Management | Psychopharmacology | Suicidality

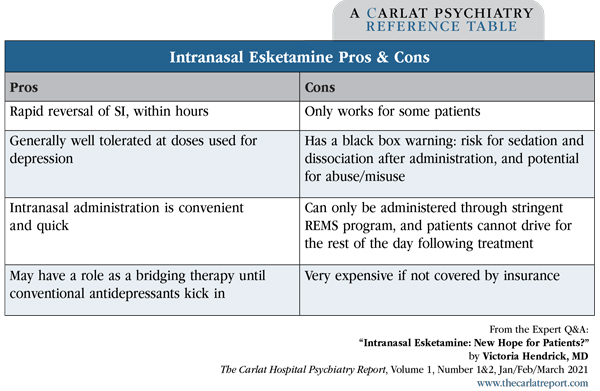

Editor in Chief, The Carlat Hospital Psychiatry Report. Chief, Inpatient Psychiatry, Olive View UCLA Medical Center. Daniel Carlat, MD. Publisher, The Carlat Hospital Psychiatry Report. Dr. Hendrick and Dr. Carlat have disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity. It’s likely your patients have asked you about esketamine. The buzz is that it’s a rapid-acting miracle cure for suicidal depression. Dr. Thomas Insel, former director of NIMH, declared that ketamine “might be the most important breakthrough in antidepressant treatment in decades” (www.nimh.nih.gov/about/directors/thomas-insel/blog/2014/ketamine.shtml). How well does it actually work? And what are its pros and cons? You’ll recall that we first started hearing about ketamine in its intravenous form, which has long been used as a preoperative anesthetic. When infused at significantly lower doses than used in the operating room, studies have found that the treatment quickly reduces suicidality, even after a single dose. The reduction of suicidal ideation occurs within hours and lasts typically for a few hours or days (Kaur U et al, Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2019; Epub ahead of print). Esketamine (Spravato), the S-enantiomer of ketamine, is delivered as a nasal spray and was developed as a more convenient alternative to IV ketamine. Esketamine recently received FDA approval as an adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder with suicidality. Some have said the FDA’s approval process was too hasty, arguing that the drug’s effects are only modest and that we don’t know much about its long-term safety. In fact, Great Britain’s version of the FDA— the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)—rejected intranasal esketamine due to uncertainties about its clinical and cost effectiveness. Esketamine clinical trials In these studies, eligible patients had treatment-resistant depression (failure of at least 2 antidepressants). Patients with bipolar disorder or psychosis were excluded. All patients were started on a standard antidepressant (either an SSRI or SNRI, open label) and then were randomly assigned to adjunctive treatment with either esketamine or placebo saline nasal spray twice weekly. The primary outcome was change in the MADRS suicidal thoughts score after 4 weeks. Across all trials, patients assigned to esketamine improved significantly more than those on placebo on the MADRS suicidal thoughts score at 4 hours. By 24 hours and at 25 days, however, there were no significant differences in these scores. Only one study found esketamine to be significantly more effective than placebo: the Transform-2 trial (Popova V et al, Am J Psychiatry 2019;176(6):428–438; published correction appears in Am J Psychiatry 2019;176(8):669). In this study, 197 patients completed the treatments, and patients assigned to esketamine had a 21-point reduction in their MADRS score vs a 17-point reduction among placebo-treated patients. Since the MADRS is a 60-point scale, a 4-point difference between drug and placebo may not seem like much, but this is similar to the effect size seen in most successful antidepressant drug trials. Meanwhile, a recent meta-analysis of all studies of esketamine conducted so far (including the studies submitted to the FDA) pooled together data from 774 patients and concluded that esketamine augmentation of an existing antidepressant is indeed more effective than placebo (Papakostas GI et al, J Clin Psychiatry 2020;81(4):19r12889). That’s a lot of information to absorb— and lost in the summary above is a critical and unique property of esketamine, which is that it reduces suicidality very quickly and dramatically. For example, in one study of 66 depressed and suicidal patients, only a quarter of esketamine patients reported suicidality at 4 hours post-dose, vs over half of placebo patients. However, this separation diminished over time—by 24 hours it was no longer statistically significant (Canuso, 2018). For patients who do benefit, how can the therapeutic response be maintained beyond the first few hours? A recent randomized controlled trial of treatment-resistant depressed patients tested longer-term treatment. In this 2-month study, esketamine was dosed at 28–84 mg initially twice weekly, then weekly, and ultimately every 2 weeks. Adjunctive esketamine beat placebo in maintaining treatment response over the 2-month study period and for an additional 2 months after the drug was stopped (Daly EJ et al, JAMA Psychiatry 2018;75(2):139–148). Higher doses also led to longer duration of efficacy. This study didn’t evaluate suicidality per se, but we know that treatment-resistant depression places patients at risk for suicide, so these results are reason for optimism. Nuts and bolts of prescribing esketamine The REMS program requires facilities to monitor patients for 2 hours after treatment for sedation, dissociation, and blood pressure changes, and patients aren’t allowed to drive themselves home after their treatment. These regulations make esketamine less accessible than some of us would like, but the effort is worthwhile if patients are able to overcome their suicidal thoughts. The protocol for patients with MDD with suicidal ideation consists of intranasal esketamine 84 mg twice weekly for 4 weeks. Each intranasal device contains 28 mg, so this dose requires 3 devices. The dose can be reduced to 56 mg twice weekly for tolerability. When insurance does not cover the cost, esketamine averages $600–$980 per dose. At the doses used to treat depression, esketamine is generally well tolerated. The most common adverse events are nausea, dizziness, somnolence, dissociation, blood pressure elevations, and headache. The dissociative symptoms usually resolve within 2 hours after esketamine administration and seem to diminish with repeated doses. Nevertheless, esketamine’s potential for misuse is a concern, and we still know little about its long-term safety. CHPR VERDICT: Esketamine appears to be an effective adjunctive agent for patients with treatment- resistant depression. But the drug’s real superpower is its rapid reversal of suicidality, which is most robust within 24 hours and disappears over the next few days. Esketamine’s antisuicide effects make it potentially useful in the following settings: 1. Psychiatric emergency rooms, to diminish acute suicidality in patients who can’t otherwise be discharged; 2. Inpatient units, for acutely suicidal patients who require one-to-one observation. In both cases, consider esketamine a bridging therapy until conventional treatments take effect. Unfortunately, the drug’s high cost will make it a difficult sell for hospital formularies.

Victoria Hendrick, MD.

Victoria Hendrick, MD.

Let’s take a deep dive into the evidence. Most of the data have come from three identically designed studies, all from the same research group (Canuso CM et al, Am J Psychiatry 2018;175(7):620–630; Fu DJ et al, J Clin Psych 2020;81(3):19m13191; Ionescu DF et al, Intl J Neuropsychopharm 2021;24(1):22–31).

Esketamine is a Schedule III controlled substance and has a high potential for abuse—as well as potentially dangerous blood pressure elevations. Because of these issues, the FDA requires that it be administered under direct supervision by a health care professional at a certified facility. To obtain certification, facilities must undergo a stringent approval process through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS). Once a hospital is certified, inpatient units do not need to enroll their patients in the REMS program, but outpatients cannot access the medication until they are enrolled. Outpatient enrollment consists of signing consent forms provided by the outpatient clinic, but even this small step may be a challenge for an acutely suicidal patient.