Serotonin Syndrome Versus NMS

The Carlat Hospital Psychiatry Report, Volume 1, Number 1, January 2021

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/chprv1n1/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Free Articles | Serotonin

Associate Professor of Clinical Neurology and Clinical Emergency Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN. Dr. Tormoehlen has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity. CHPR: Can you start by telling us about yourself? CHPR: You recently wrote a review of neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) and serotonin syndrome. Can you tell us about these syndromes? CHPR: What’s your approach to differentiating the two? CHPR: Can you give us some examples? Table: Examples of Medications That Contribute to Serotonin Syndrome CHPR: Do you also take the medication’s serotonergic potency into account? CHPR: So we look for the number and potency of serotonergic medications that the patient is taking. Should we also look for drug interactions? CHPR: What are the symptoms of these mild versions? CHPR: What about NMS? Is that predictable? CHPR: But many patients can’t give us an accurate medication history, or they might be on antidopaminergic and proserotonergic medications. How else can we diagnose NMS vs serotonin syndrome? Table: Differentiating Serotonin Syndrome From Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome CHPR: Are there any distinctive lab findings? CHPR: What about motor features? CHPR: What does clonus look like? CHPR: How do you induce clonus? CHPR: Once you’ve established the diagnosis, what are the best treatments? Table: Management of Serotonin Syndrome and NMS CHPR: And what if the patient is not only stiff but also hyperthermic? CHPR: So these measures help serotonin syndrome as well as NMS. Are there any treatments that are specific for NMS or serotonin syndrome? CHPR: And for NMS? CHPR: Once you’ve begun these interventions, how long does it take for patients to recover? CHPR: And when can you reinstate the medications that they were taking? CHPR: What about restarting antipsychotics in patients who recovered from NMS? CHPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Tormoehlen.

Laura Tormoehlen, MD

Laura Tormoehlen, MD

Dr. Tormoehlen: Sure. I am a neurologist and have completed a medical toxicology fellowship. I am an attending physician for the neurology service at Indiana University Health Methodist Hospital, as well as for the toxicology service at Methodist, University, Riley, and Eskenazi Hospitals. I also run the neurotoxicology clinic here at Indiana University and serve as the vice chair of clinical practice for the neurology department.

Dr. Tormoehlen: Sure. Let’s start by reviewing some of the basics of these two conditions. NMS is a rare but potentially life-threatening reaction to antipsychotic medications, due to blockage of dopamine receptors. Serotonin syndrome results from excessive serotonin activity in the central nervous system and can range from mild to severe, even potentially fatal. Both disorders often present with muscle rigidity, hyperthermia, and altered mental status.

Dr. Tormoehlen: Once you see either an increased tone or an elevated temperature of unknown origin, then the next step is a review of the patient’s medications, keeping in mind that many drugs we might not think of as serotonergic can be serotonergic as a secondary mechanism.

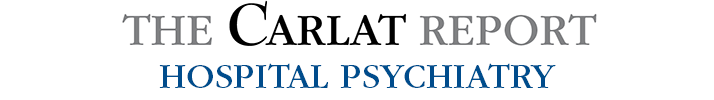

Dr. Tormoehlen: There are several ways drugs can be proserotonergic (ie, lead to increased serotonin activity). For example, they can increase serotonin release, inhibit serotonin metabolism, inhibit serotonin reuptake, or activate serotonin receptors (Editor’s note: See table below). Fentanyl, linezolid, and OTC drugs like dextromethorphan are all examples of proserotonergic medications that tend to be overlooked. You also want to get information on any supplements like St. John’s wort.

Dr. Tormoehlen: Yes, that matters. A reasonable example would be triptans. Triptans are proserotonergic, and if you prescribe a triptan to a migraine patient who is also on amitriptyline as a prophylaxis, your EMR will send you an alert. However, triptans are fairly weakly proserotonergic, so your patient would likely have to be on a heavy regimen of the triptan on top of high doses of other serotonergic meds to develop serotonin syndrome.

Dr. Tormoehlen: Yes, because some drugs inhibit cytochrome P450 enzymes and can cause serotonin syndrome when they’re combined with serotonergic medications. For example, ciprofloxacin, which inhibits CYP3A4, or fluconazole, which inhibits CYP2C19, can cause serotonin syndrome in combination with certain SSRI or SNRI antidepressants. Serotonin syndrome is predictable. If a patient takes enough serotonergic drugs, especially if they have different mechanisms, you will observe serotonin syndrome. It’s more common than we realize because mild cases occur that we don’t think of as being serotonin syndrome.

Dr. Tormoehlen: Anytime you counsel your patients, “You might have diarrhea or tremor from the addition of this medication to your regimen,” you’re telling them they might have mild serotonin syndrome. It’s important to review patients’ side effects carefully because they can indicate the beginning of serotonergic excess. These milder forms of serotonin syndrome tend to happen as adverse effects from a therapeutic dose, like from starting a new drug or increasing the dose. The acute-onset, more severe cases are typically from overdoses or excessive amounts of proserotonergic drugs.

Dr. Tormoehlen: NMS is much more idiosyncratic and difficult to predict. If you suspect it, you want to check carefully for antidopaminergic medications besides the antipsychotics, although there aren’t nearly as many of those as there are serotonergic medications.

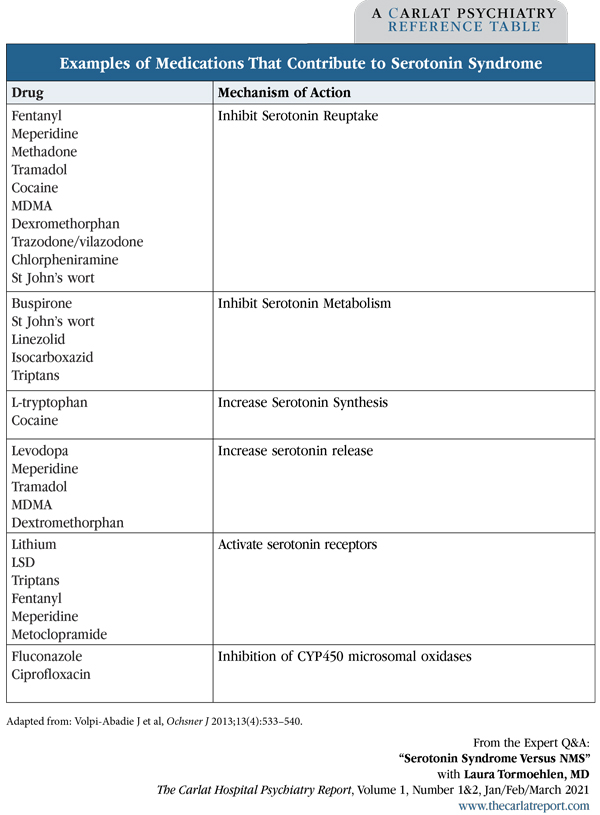

Dr. Tormoehlen: One way to tell the difference is onset (Editor’s note: See table below for more tips). Serotonin syndrome is much more likely to be acute in onset, on the order of hours, and NMS is likely to be subacute in onset—so days, roughly speaking. If your patient was fine 3 or 4 hours ago and now suddenly they are hyperthermic and rigid, it’s much more likely to be serotonin syndrome.

Dr. Tormoehlen: Not really. With both, you can see elevated creatinine kinase (CK) levels (Editor’s note: CK is also known as creatinine phosphokinase, or CPK), so labs won’t help differentiate one from the other. The elevated CK results from the muscle rigidity, as CK is an enzyme that leaks out of damaged muscle tissue.

Dr. Tormoehlen: Motor features do help differentiate one from the other. Serotonin syndrome classically manifests with clonus.

Dr. Tormoehlen: Clonus refers to involuntary, rhythmic muscle contractions. Interestingly, it tends to happen more in the lower vs upper extremities, so you must check the legs—not only for tone, but also for clonus. Sometimes our bedside exam gets a little too quick, and we check for tone in the arms and maybe skip the legs, but if you do this, you might miss the increased tone and clonus. Conversely, NMS is primarily about rigidity—typically described as “lead pipe”—rather than clonus. You might observe a substantial increase in tone, even to the degree that you can’t check for inducible clonus at the ankles because the tone is so high.

Dr. Tormoehlen: If you briskly flex the patient’s foot upward, you’ll see a rhythmic beating of the foot and ankle. Make sure you sustain that passive dorsiflexion of the foot. If the rhythmic beating continues beyond a couple of beats, that would be abnormal.

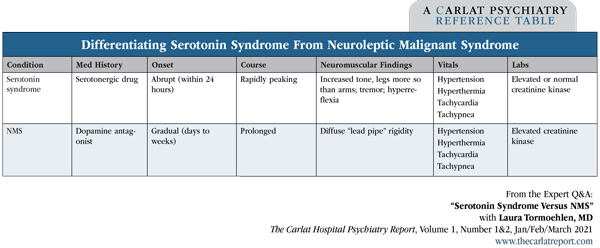

Dr. Tormoehlen: First of all, stop any drug that could be contributing to the symptoms: serotonergics, neuroleptics, adrenergics, anticholinergics, etc. The differential diagnosis includes other syndromes besides NMS and serotonin syndrome, such as sympathomimetic syndrome and anticholinergic syndrome, so you want to stop all potentially offending drugs. And then for treatment, fortunately, we treat NMS and serotonin syndrome the same way at the beginning. First-line treatment is benzodiazepines. We usually use lorazepam or diazepam. Essentially, we’re trying to “chill the brain out.” A good way to make the brain be quieter regardless of which neurotransmitter system is overreacting is GABA agonist therapy, like with benzos (Editor’s note: See table below for more information).

Dr. Tormoehlen: Then we’ve got to get them cooled. Benzodiazepines will also help with hyperthermia because they decrease muscle tone. The hyperthermia is mostly from overgeneration of heat from muscle activity, so antipyretics won’t be effective, but if you can relax the muscles, then you will decrease the temperature. External cooling is important. If your patient is hot, with a temperature greater than 104ºF, then prophylactic intubation, mechanical ventilation, and pharmacologic paralytics may be necessary, although that isn’t commonly required.

Dr. Tormoehlen: If you are sure of what you’re treating, then there are antidotes that can be aimed directly at the neurotransmitters causing the problem. For serotonin syndrome, it is the serotonin antagonist cyproheptadine, which you can only give by mouth (adult dosing: 12 mg followed by 2 mg q2 hours until improvement, then 8 mg q6 hours maintenance dosing). It’s an antihistamine and it’s also anticholinergic, so if there’s a chance your patient has anticholinergic syndrome, then you don’t want to use this.

Dr. Tormoehlen: For the management of NMS, bromocriptine—a dopamine agonist—is the potential antidote (2.5–5 mg orally or by NGT every 8 hours). The second agent we might add, but only if the rigidity is severe, would be dantrolene (3–5 mg/kg IV divided TID, or orally at 100–400 mg/day QID). Dantrolene is a muscle relaxant, so it only treats the rigidity; it does not help with any of the CNS symptoms. Most of the time we get away with using benzodiazepines plus or minus bromocriptine, without the dantrolene. If dantrolene is needed, you will need to monitor hepatic function as dantrolene can cause liver toxicity. In addition, bromocriptine has some proserotonergic activity, so it should be avoided if serotonin syndrome remains possible.

Dr. Tormoehlen: With either syndrome, patients can be very ill at initial presentation, but with good care they generally recover fully. They will usually improve quickly with aggressive management in either syndrome, but NMS takes longer to completely recover, so patients need a management plan on the order of weeks. If serotonin syndrome is severe, then it may take several days to recover in the ICU, but once patients are medically stable and ready for discharge, they typically do not require any outpatient management; once it’s done it’s done.

Dr. Tormoehlen: It’s much easier in serotonin syndrome because those patients typically either overdosed or had a drug interaction. Acute serotonin syndromes are found in the overdose patients; those with drug interaction tend to be much less severe. Typically, you’d wait 24–48 hours after complete resolution of their syndrome, and then they can go back to previously prescribed medicines as long as you limit the number of proserotonergics and restart only the most important medications. If possible, start with one agent at low dose.

Dr. Tormoehlen: Because NMS is an idiosyncratic reaction, it is much harder to predict who’s going to get it. And once a patient has had it, we tend to have trepidation about resuming antipsychotics. But if the indication to resume is strong, you can restart an antipsychotic as long as you start at a low dose and titrate up slowly. You want to wait until the symptoms are completely resolved, at least 2 weeks, and then pick a second-generation antipsychotic because they appear less likely to cause NMS. Also, you want to choose a different drug than the one that caused the NMS, and don’t use depot injections.