An Off-Label Guide to Gabapentin

The Carlat Psychiatry Report, Volume 20, Number 2, February 2022

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/tcprv20n2/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | Editorial Information | PDF of Issue

Topics: Alcohol use disorder | Anxiety | Anxiety Disorder | Cannabis | Free Articles | gabapentin | Pregabalin

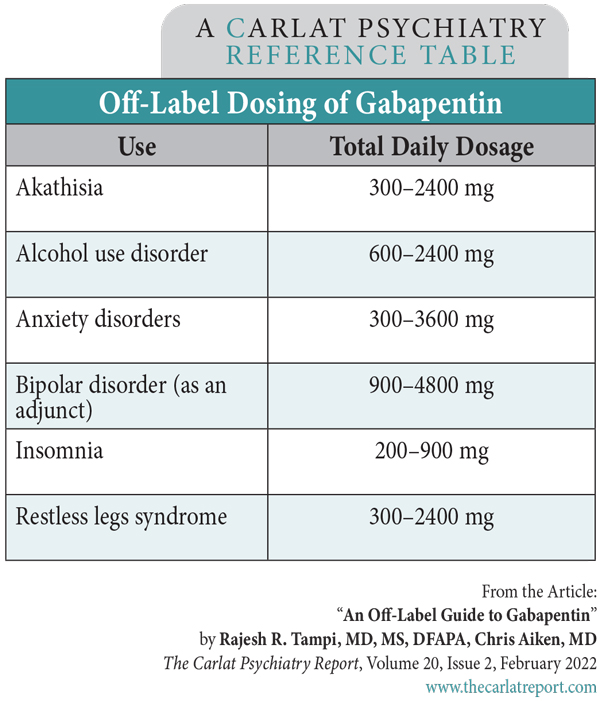

Rajesh R. Tampi, MD, MS, DFAPA. Chris Aiken, MD. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity. Gabapentin (Neurontin) is not a medication that would make the FDA proud. Less than 1% of its outpatient use is for an FDA indication, and a good portion of the off-label use takes place in psychiatry. These trends sparked a backlash in the 2000s, when Pfizer paid a $1.3 billion fine for misleading marketing practices. Recent reports of misuse of gabapentin and its GABAergic cousin, pregabalin (Lyrica), have added to those concerns. In this article, we’ll look at where gabapentin fits in psychiatric practice. Anxiety disorders By comparison, pregabalin has much better evidence in anxiety disorders, with eight randomized controlled trials at a dose range of 150–600 mg/day involving over 2000 patients with generalized and social anxiety disorders, including several with long-term follow-up (Generoso MB et al, Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2017;32(1):49–55). Pregabalin sees more use for anxiety in Europe, where it has regulatory approval in generalized anxiety disorder, while US psychiatrists lean toward gabapentin. The evidence is clearly in pregabalin’s favor, but gabapentin does have a tolerability advantage, with lower rates of weight gain and ataxia (Shaheen A et al, Pak J Med Sci 2019;35(6):1505–1510). Addictions Gabapentin may also be useful for alcohol withdrawal, but with a caveat. Although it was generally effective in controlled trials that compared it with benzodiazepines and phenobarbital, there were a few seizures during the gabapentin taper—not enough to raise statistical alarms, but enough to give us pause. It does improve cravings, anxiety, and sleep during withdrawal, so it may still have a role as an adjunct to more established methods like a benzodiazepine taper, or its use should be confined to patients with less severe dependence. A typical schedule starts at 1200–2400 mg/day in three or four divided doses, tapers to 600 mg/day over four to seven days, then drops in increments of 300 mg or smaller every few days until reaching zero (Leung JG et al, Ann Pharmacother 2015;49(8):897–906). Alternatively, it may be continued long term to prevent relapse, a use that is endorsed by the APA guidelines on alcohol use disorders. We have only one controlled trial for gabapentin in cannabis use disorder, but this limitation is tempered by the fact that there are few pharmacologic options for this disorder. In this small, placebo-controlled study, gabapentin reduced cannabis withdrawal symptoms, increased abstinence, and improved executive functioning (Mason BJ et al, Neuropsychopharmacology 2012;37(7):1689–1698). Gabapentin is by no means a panacea for addictions, however. It failed in controlled trials of cocaine, methamphetamine, benzodiazepine, and opioid use disorders. Recent reports suggest particular caution in patients with opioid use disorder, as gabapentin may increase the risk of overdose and hospitalization in this group (Evoy KE et al, Drugs 2021;81(1):125–156). Bipolar disorder Gabapentin is not reliable on its own in bipolar disorder, but two placebo-controlled trials suggest it may have a role as adjunctive therapy. It augmented lithium in acute mania and had mild preventive effects over a year when added to various mood stabilizers. As encouraging as these results are, both came from small trials with a total n of 85 (Astaneh AN and Rezaei O, Int J Psychiatry Med 2012;43(3):261–271; Vieta E et al, J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67(3):473–477). In practice, gabapentin is best reserved for treating bipolar disorder in patients with comorbidities like anxiety and alcohol or cannabis use disorders. Table: Off-Label Dosing of Gabapentin Restless legs syndrome and pain Gabapentin’s RLS approval is reserved for gabapentin enacarbil (Horizant), a prodrug that delays absorption by attaching the medication to an enacarbil molecule. However, there are three reasons to prefer the original gabapentin when treating RLS besides the higher cost of the patented Horizant: Although lacking in FDA approval, the original gabapentin was effective for RLS in half a dozen small studies. The usual dose is 300 mg before bed (which is equivalent to 600 mg of Horizant), but studies have gone as high as 2400 mg. Akathisia, sleep, and hot flashes Gabapentin is often used as a hypnotic, and this is supported by small controlled and open-label trials where it improved sleep duration and quality (eg, increased slow-wave sleep) at 200–900 mg/day (Furey SA et al, J Clin Sleep Med 2014;10(10):1101–1109). In practice, this means gabapentin may not help your patients fall asleep faster, but it can deepen their sleep and reduce nocturnal awakenings. Women with post-menopausal vasomotor symptoms are good candidates for this hypnotic use, as gabapentin reduced hot flashes in several controlled trials (Saadati N et al, Glob J Health Sci 2013;5(6):126–130). Risks Dosing tips Gabapentin is excreted entirely by the kidneys, which means it avoids hepatic drug interactions, but the dose needs to be lowered as creatinine clearance (CC) declines, a common problem in older patients. The usual dose range of 900–3600 mg/day is lowered to 400–1400 mg/day for a CC of 30–59 mL/min, 200–700 mg/day for a CC of 15–29 mL/min, and 100–300 mg/day for a CC below 15 mL/min (such patients usually require dialysis). With a six-hour half-life, gabapentin can be divided three times daily for anxiety disorders and dosed at bedtime for sleep disorders. When stopping the medication, taper gradually to avoid withdrawal symptoms, which are rare and include tremor, sweating, restlessness, insomnia, and a lower threshold for seizures (Mersfelder TL and Nichols WH, Ann Pharmacother 2016;50(3):229–233). (Editor’s note: See the table “Off-Label Dosing of Gabapentin” on page 4.) TCPR Verdict: Gabapentin is probably used more often than the evidence supports. Consider it for alcohol and cannabis use disorders, and insomnia with hot flashes or nocturnal awakenings. Both pregabalin and gabapentin are effective in anxiety disorders, but pregabalin should be tried first as it has the better data.

Professor of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University. Chairman, Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, Cleveland Clinic Akron General, and Chief of Geriatric Psychiatry, Cleveland Clinic.

Editor-in-Chief of TCPR. Practicing psychiatrist, Winston-Salem, NC.

Gabapentin may be effective for social anxiety and panic disorders at a dose of 900–3600 mg/day. The supporting clinical trials are industry sponsored, and while the methodology is solid (randomized, double blind, placebo controlled), the studies were small—only two trials with a total of 172 participants (Pande AC et al, J Clin Psychopharmacol 1999;19(4):341–348; Pande AC et al, J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;20(4):467–471). Other studies report benefits in nonspecific anxiety, such as before surgery and in breast cancer survivors, where gabapentin worked better than placebo in two large trials (total n = 630) at a dose range of 300–1200 mg/day (Tirault M et al, Acta Anaesthesiol Belg 2010;61(4):203–209; Lavigne JE et al, Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012;136(2):479–486).

Despite concerns about gabapentin misuse, the medication does have a role in alcohol and cannabis use disorders. Patients who take it for alcohol use disorders report fewer days of heavy drinking, with an effect size in the medium range (0.4) from seven randomized controlled trials (Ahmed S et al, Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2019;21(4):19r02465). Gabapentin also improves sleep quality during recovery from alcohol use. The dose range was 300–3600 mg/day, with most settling in around 900 mg/day.

Long ago, there was a consensus in psychiatry that all anticonvulsants had antimanic effects. In 2000, gabapentin became the first anticonvulsant to challenge that idea, with a negative trial in bipolar mania that was followed by similar disappointments from topiramate and oxcarbazepine (Pande AC et al, Bipolar Disord 2000;2(3 Pt 2):249–255).

Gabapentin has only three FDA indications: partial seizures, post-herpetic neuralgia, and restless legs syndrome (RLS). Although used widely in pain disorders, it only has clear benefits in post-herpetic neuralgia and diabetic peripheral neuropathy, and is not considered effective for low back pain, sciatica, spinal stenosis, or migraines (Mathieson S et al, BMJ 2020;369:m1315).

Treatments for RLS often reduce akathisia, and gabapentin has promising results for this antipsychotic side effect, as evidenced in open-label trials at doses of 300–3600 mg/day.

Gabapentin has no serious warnings, but common adverse effects include sedation, fatigue, dizziness, imbalance, tremor, and visual changes from nystagmus.

Gabapentin is one of the rare psychiatric meds with “nonlinear pharmacokinetics.” That means serum levels start to plateau after a certain dose and rise sluggishly from there. For gabapentin, that dose is 900 mg. At 900 mg, 540 mg of the drug is absorbed; at 1200 mg, only 564 mg is absorbed; and at 2400 mg, a measly 816 mg makes it into the bloodstream. This slowdown occurs because the transporters that absorb gabapentin are easily saturated at higher doses (the prodrug Horizant was developed to overcome this limitation, but it does so at a cost).![]() To learn more and earn additional CMEs, search for Carlat in your favorite podcast store and subscribe to our weekly podcast.

To learn more and earn additional CMEs, search for Carlat in your favorite podcast store and subscribe to our weekly podcast.