How to Distinguish the Dementias

The Carlat Geriatric Psychiatry Report, Volume 1, Number 1&2, January 2022

https://www.thecarlatreport.com/newsletter-issue/cgprv1n12/

Issue Links: Learning Objectives | PDF of Issue

Topics: Free Articles

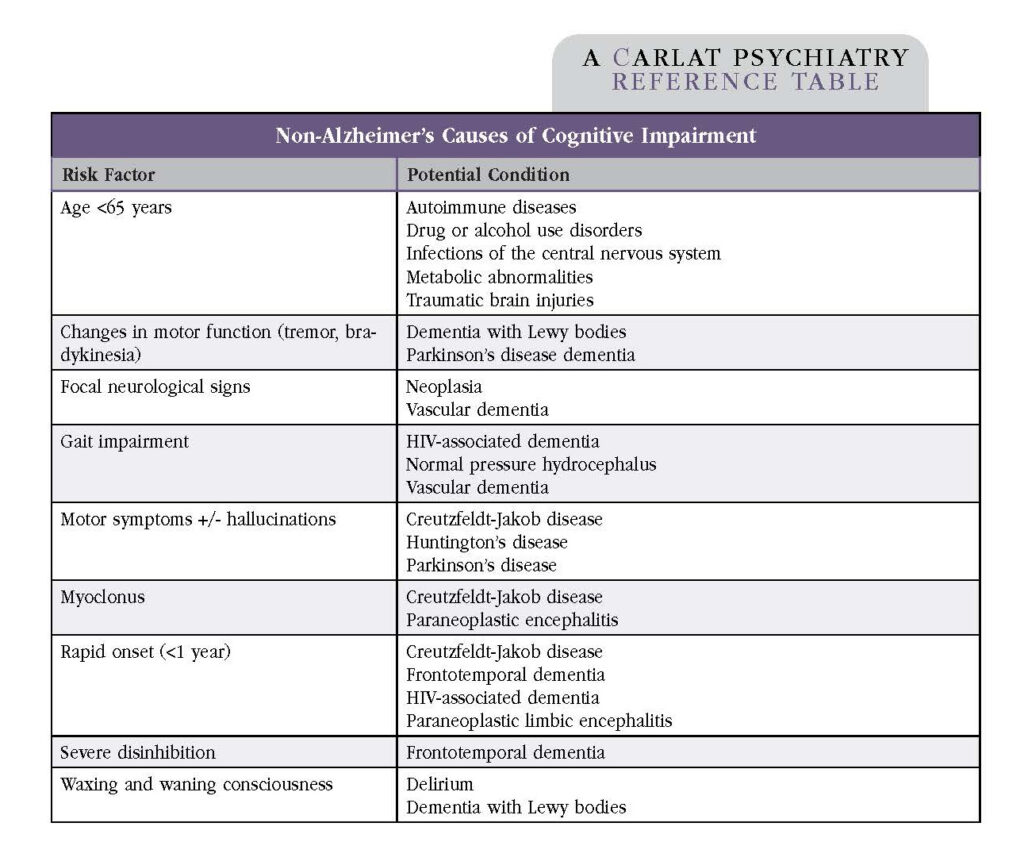

Jose Ribas Roca, MD. Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX. Dr. Roca has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity There are several types of dementia, and each has a different prognosis and treatment course. In this article I’ll outline my approach for distinguishing between the most common varieties—Alzheimer’s, vascular, Lewy body, and frontotemporal. In addition, I’ll cover how to differentiate between mild and major neurocognitive disorder (NCD). Table: Differentiating Among the Most Common Types of Dementia Alzheimer’s disease The most common dementia is Alzheimer’s disease (AD), which accounts for 60%–70% of dementia cases (www.tinyurl.com/5a9uubva). Symptoms usually start after age 65 and progress slowly. If a patient’s symptoms begin before age 65, this is considered early-onset AD. The cornerstone symptom of AD is short-term memory loss, which leads to the repetition of questions and stories. AD also impacts executive functioning. Language and social cognition are relatively preserved until later in the illness. Neuropsychiatric symptoms such as agitation, delusions, hallucinations, and apathy tend to occur in the moderate to severe stages, although anxiety and depression may appear earlier. AD usually progresses gradually, without plateaus. Although AD is the most common dementia, it’s important to think through alternative explanations prior to making the diagnosis. Table: Non-Alzheimer’s Causes of Cognitive Impairment Vascular dementia Vascular dementia (VD) is the second most common dementia, accounting for 15%–20% of dementia cases. Like AD, it becomes more prevalent as people age. VD is caused by damage to the brain’s blood vessels. I suspect VD when patients have vascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, or high cholesterol, especially if there has been end-organ damage. The clinical symptoms of VD vary depending on the location and size of damaged brain tissue. VD can progress in a stepwise pattern, such as following strokes, or it may be gradual, such as in progressive microvascular deterioration. Executive function is commonly affected. Dementia with Lewy bodies Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) usually progresses gradually after the age of 60. I suspect DLB when a patient presents with core symptoms of Parkinsonism, recurrent visual hallucinations, or fluctuating cognition. In DLB, cognitive impairment occurs before motor symptoms, whereas in Parkinson’s disease, cognitive impairment occurs in the context of established motor symptoms. REM sleep behavior disorder and neuroleptic sensitivity are often present in DLB. I always ask about whether the patient is experiencing well-defined visual hallucinations and acting out their dreams. I assess gait for instability and bradykinesia, and I look for abnormal movements such as a “pill rolling” tremor. Any of these signs would warn me against a trial of antipsychotics, since patients with DLB often have severe neuroleptic sensitivity. If an antipsychotic is necessary, I consider low-dose quetiapine first, followed by pimavanserin or clozapine. Frontotemporal dementia Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is divided into two variants: behavioral variant FTD (bvFTD) and the language variant, also known as primary progressive aphasia (PPA). Family members may be puzzled and concerned by bvFTD, especially when a patient’s personality changes include behavioral disinhibition and socially inappropriate behavior. Apathy, loss of empathy, and perseverative or compulsive behavior are often present. PPA may present with a loss of word comprehension but intact verbal fluency, making the meaning of a patient’s speech incomprehensible. Alternatively, patients may experience early speech impairments including the loss of fluency, difficulty naming (anomia), and difficulty constructing sentences while preserving individual words (agrammatism). Mixed dementia The exact prevalence of mixed dementia is not known. According to pathology reports, mixed dementia is the most common form of dementia and found in 46% of persons with clinically diagnosed AD (Arvanitakis Z et al, JAMA 2019;322(16):1589–1599). It is more common in older adults, and the most common combination is AD + VD. Distinguishing between mild and major NCD When a patient reports memory concerns, I set out to identify whether the memory issues are due to depression, aging, mild cognitive impairment, or dementia. Depression in late life is often the harbinger for dementia. I first identify which neurocognitive domains are affected (complex attention, executive function, learning and memory, language, perceptual-motor, and social cognition), as well as the order by which each domain is impacted. Most patients present with memory impairment plus impairment in at least one additional domain. I verify that the deficit is a significant decline from a previous level of functioning. Identifying whether a patient’s symptoms are due to mild NCD (“mild cognitive impairment”) or major NCD (“dementia”) holds important prognostic implications. To make this differentiation, I go over a patient’s ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). The diagnosis of major NCD requires interference with ADLs, such as bathing or dressing, whereas the diagnosis of mild NCD requires impairment in IADLs, such as managing finances and preparing meals. People with mild NCD require greater effort, compensatory strategies (such as lists), or accommodations, but they should still be able to perform their ADLs independently. Mild NCD does not necessarily progress to dementia. Annual conversion rates are often 10%–15% in clinic samples and 3.8%–6.3% per year in community-based studies (Farias ST et al, Arch Neurol 2009;66(9):1151–1157). Meds, labs, and imaging When determining potential causes of cognitive impairment, I begin by reviewing a patient’s medication list to identify culprits (anticholinergics, antihistamines, benzodiazepines, and opioids are top offenders). I order laboratory tests to rule out metabolic and infectious processes that can mimic dementia. Screening labs include a complete blood count, electrolytes, glucose, liver function, renal function, and thyroid profile. Urinalysis is particularly important, because changes in cognition are often the first sign of a urinary tract infection in the elderly. I often order a fasting lipid profile and hemoglobin A1c in patients with risk factors for VD. For many patients, I will consider vitamin B12 and folate levels. In patients with a history of high-risk behavior, I order HIV antibodies and syphilis tests. Structural brain imaging can help differentiate among dementias. A brain CT can show areas of cortical atrophy. Patients with AD may exhibit atrophy in the hippocampus and temporoparietal cortex, while patients with FTD may exhibit atrophy in the frontal and temporal lobes. Ventricular enlargement from normal pressure hydrocephalus will be evident on a CT scan. For VD, MRI is favorable, as it provides greater detail about prior strokes, small vessel disease, or subcortical ischemic changes. Additional imaging is usually reserved for complex cases with atypical presentation. FDG-PET differentiates AD from FTD, amyloid-PET provides supportive evidence for AD, and a DaTscan differentiates between AD and DLB (although it does not distinguish DLB from other Parkinsonian disorders). Memory disorder clinics may offer these tests as part of research protocols. If I suspect rare causes of dementia, I will refer the patient to neurology (for more on rare causes of dementia: www.thecarlatreport.com/raredementias). Warning signs include an early age of onset (age <65 years), rapid progression of symptoms, or the presence of an abnormal neurologic exam (Arvanitakis et al, 2019). The neurologist may consider further workup, such as an EEG and spinal fluid exams to look for periodic sharp wave complexes and 14-3-3 proteins in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. A sleep study is indicated when there is suspicion of sleep apnea or REM sleep behavior disorder; the latter is common in people with Parkinson’s disease and DLB. Cognitive screening tools I find standardized screening tools to be helpful in patients of advanced age. The National Institute on Aging has a website that includes cognitive screening tests and tools for diagnosis (www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-dementia-resources-for-professionals). Keep in mind that screening tools tend to overestimate cognitive impairment in the elderly, individuals with less than eight years of school, and ethnic minorities. They may also fail to detect cognitive impairment in highly educated individuals. They do not distinguish between dementia types or cognitive issues due to depression. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; www.tinyurl.com/y59tcxhk) is considered the gold standard of dementia screening. However, it is slowly starting to fall out of favor, as shorter tests have similar sensitivity and specificity. I prefer the Mini-Cog (www.mini-cog.com), which takes less than five minutes and entails a three-word recall and clock-drawing exercise. The Mini-Cog is more sensitive and is less affected by education level than the MMSE, but it has similar specificity (Milian M et al, Int Psychogeriatr 2012:24(5):766–774). I also use the Saint Louis University Mental Status exam (SLUMS; www.slu.edu/medicine/internal-medicine/geriatric-medicine/aging-successfully/pdfs/slums_form.pdf), which is in the public domain. When I feel the need to test more cognitive areas, such as attention, language, and executive function, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA; www.mocatest.org) screening test covers all major domains. Finally, if I suspect FTD, the Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB; www.tinyurl.com/yw99h8pw) is very useful to differentiate FTD from AD. To stage dementia, I use the Clinical Dementia Rating scale (CDR; www.tinyurl.com/smw2fr6y). Carlat Verdict: Taking the time and effort to differentiate among the types of dementia helps the clinician look for symptoms that may otherwise go unreported. As a result, the clinician will be better suited to advise patients and families on optimal management and to avoid side effects from unnecessary medications.

Click to view as a full-sized PDF.